When veterinarians or horse owners are surveyed about the problems they see in today’s horses, lameness usually ranks in the top two concerns (generally with colic).

In order to better understand degenerative joint disease (DJD)—a major cause of lameness in horses—American Regent Animal Health (makers of Adequan® i.m. (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan) brought together a group of equine practitioners ranging from a new graduate in equine practice to leading imaging and lameness practitioners to researchers and surgeons. The company asked EquiManagement to moderate a half-day discussion on the diagnosis and treatment of DJD. We have gleaned the following tidbits and advice from these practitioners to share with you.

This group included Kent Allen, DVM, owner of Virginia Equine Imaging and a founder of the International Society of Equine Locomotor Pathology (ISELP); Robin Dabareiner, DVM, PhD, DACVS, who worked at Texas A&M for 23 years before working at Waller Equine Hospital in Texas; Christopher E. Kawcak, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, ACVS Founding Fellow/MIS, who is the director of Equine Clinical Services at Colorado State University (CSU); Zach Loppnow, DVM, an associate veterinarian at Anoka Equine Veterinary Services in Minnesota; Rick Mitchell, DVM, MRCVS, DACVSMR, an owner of Fairfield Equine Associates and a founding member of ISELP; Kyla Ortved, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, the Jacques Jenny Endowed Term Chair of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center; Kelly Tisher, DVM, managing partner at Littleton Equine Medical Center in Colorado; and Gary White, DVM, owner of Sallisaw Equine Clinic in Oklahoma. All are paid consultants of American Regent, Inc. The opinions expressed by the consultants may not be the opinions of American Regent Animal Health or American Regent, Inc.

Equine Demographics and DJD

There is a trend in the United States toward an aging equine population with fewer foals born, according to the 2015 National Animal Health Monitoring System survey.1 This means that a larger portion of the horse population that veterinarians are serving is aged, many with second careers—with a smaller population of up-and-coming performance horses to replace older campaigners moving out of top-tier competition.

Dabareiner said that probably 50-60% of her caseload consists of “playday” horses from 15-25 years old. “Those are horses that have been—in their prime—professional, top-notch horses,” she explained. “Now they’re not fast enough, a little too crippled, too much arthritis for the high-tier riders. So, they’re going down to these kids that are anywhere from 5 years old to 16 years old. They do numerous events all day long. They’re very tough horses with a lot of problems.”

Early in the discussion, Allen brought up a good point that was supported by the group. This was that any changes veterinarians are seeing in the frequency of DJD among today’s horses are “probably due more to us getting better at diagnosis than the animals getting more disease.”

Allen mentioned a project that included about 700 pre-purchase exams his team has yet to turn into a research paper. He said, “Easily for 40-50% of those horses, we found radiographic arthritic changes somewhere in their joints.”

Dabareiner added that older “playday” horses making up a bigger portion of her patient base do have an overall increased incidence of DJD. “I think it’s more the type of horse—the older horse—that I’m looking at now.”

Kawcak brought in the debate between radiologists, sports medicine clinicians and surgeons at CSU about what is defined as osteoarthritis (OA). “I think it’s not so much the incidence has gone up, but [that] the definition has probably scaled a little bit over the last few years.”

He noted that people do use the terms DJD and OA interchangeably in both veterinary and human medicine. “OA is probably more commonly used today as we understand more the bone (osteo…) part of the disease process,” he said.

Kawcak said there is one segment of the equine population in his caseload that appears to have increased DJD incidence. “I deal with a fair number of young cutting horses, both here [at CSU] and in Texas, and have had the opportunity to follow a lot of them. I do think in those young, hardworking, active athletes with that big push in their 3-year-old year that the incidence [of DJD] has probably gone up, especially in stifles and hocks. We’ve done some studies here to show that that incidence of hock lesions does have an impact on performance, at least during their limited age event years.”

Loppnow said when looking at the lameness profile of the range of horses seen at Anoka Equine that “greater than half of what we’re doing is osteoarthritis of some kind. We see it a lot.”

He noted that performance horses are getting “pushed longer” in terms of their athletic careers. Loppnow said he thinks because of that “desire to stretch that performance life of the horse” they are seeing the incidence of osteoarthritis going up. “If you use the definition of a senior horse as being 15 years and older, that’s a large percentage of our caseload.”

Mitchell said that his practice’s caseload is “getting older.” As he explained, “In several reviews that we’ve done recently and in a paper we just had accepted for publication, the mean age of horses in our practice—which is hunters/jumpers and dressage horses and a few eventers—is 11 years.

“Those horses are generally reaching their peak in performance and capability,” he said. “But they’re also starting to acquire some of the wear and tear inherent to the jobs that they do.”

He added that among the older horses in his practice that were high-performance competitors at one point, many are 15 years old or older. “They certainly do demonstrate a significant amount of osteoarthritic changes,” he stated. “It certainly is a major portion of what I do every day.”

Ortved has a caseload of about 40% Thoroughbred racehorses, 40% sporthorses (mostly English performance animals) and 20% other types, including backyard and lower-level performance horses. She said that she sees a lot of pre-purchase films from clients looking to buy young horses in Europe. “I’m finding that a lot of those pretty young horses have radiographic changes. And maybe, like Chris [Kawcak] said, we’re a little bit over-sensitized to the radiographic changes and describing joints that maybe historically we wouldn’t have diagnosed as OA.”

Ortved also works with a lot of off-the-track Thoroughbreds for rehoming and rescue organizations. “We screen a lot of their horses that come off the track before they’re attempted to get adopted out,” she said. “A lot of those horses are quite young … 3-, 4-, 5-year-olds coming off the track. We see a subset of them that have end-stage OA that end up being put down for humane reasons as they have such severe lameness. Then we see some that are not as badly affected but will require a lot of treatment to keep sound, or they’re just put into more of a low-level type of work.”

At New Bolton Center, Ortved said they recently acquired a PET (positron emission tomography) scan to go along with their MRI and CT scanners. “We’ve been doing more imaging and more diagnostics on horses that otherwise probably we wouldn’t have in the past,” she said. “I think we are seeing things at an earlier time point and are a little bit more able to pinpoint and diagnose joint injuries that we wouldn’t have been able to diagnose in the past.”

Tisher noted that in the Littleton practice’s caseload, they have about 60% English performance horses and 40% Western performance horses. While he doesn’t think the actual incidence of DJD is changing, he noted that there are more older horses on which owners will ask veterinarians to “do more management than maybe we have before.”

He, too, agreed that veterinarians will be seeing more and more older horses. But he also mentioned the “diagnosis dilemma” with young horses. “Where does degenerative joint disease become the diagnosis, when you maybe don’t have imaging changes but you do have the strong sense of synovitis, capsulitis and [the] need to manage that horse at a young age?” Tisher asked. In addition, he mentioned the “strong desire from trainers” who notice performance issues and want veterinarians to address them.

He said the futurity barrel horse is a subset of patients for his practice in which owners are investing a tremendous amount of money. “That young group potentially has some of the signs of degenerative joint disease, but maybe doesn’t have the imaging signs of OA. I think that’s a subset that is a challenge,” said Tisher.

White has a practice of about 70% Western performance horses ranging from barrel racers and team ropers to rodeo event horses. He noted that the Western rodeo performance horse over the last 25-30 years has had a small professional presence, with most people participating as a hobby. “But now there are a lot of people who have invested a lot of money in these horses,” he said. “There’s a lot of money to be earned with these horses.

“When I started out in this business over 40 years ago, you seldom saw a high-level Western performance horse over 13, 14 or 15 years old,” he explained. But he added that today, “we see high-level horses in these disciplines up to 20 years old. Then a lot of them switch to the ‘playdays’ and school horses and perform into their late 20s. So yes, we’re seeing more of an incidence of arthritis.”

Diagnostics

There was a consensus that as equine diagnostics become better, easier and more available—particularly with the advent of the standing CT scanner—that more disease will be found. That doesn’t necessarily mean there is an increase in DJD, but rather that the ability to find it—and identify it earlier in the disease process—will bring more attention to this problem in all ages of horses.

There also was a consensus that owners and trainers have caused DJD to be “under-diagnosed and over-treated.”

White explained it like this: “People will go to a veterinarian and get eight or 10 joints injected at one trip. I question whether that horse received a good examination and a good diagnosis.”

Tisher agreed with White. However, he said that in his practice, over the last decade or so, he’s felt that clients and trainers were better at valuing the veterinarian’s exam to obtain a proper diagnosis before beginning treatment.

Mitchell said he doesn’t think veterinarians are over-diagnosing, but he does think there’s a trend to over-treat. “I think there is a trend from trainers and owners to ‘do whatever you can to fix the horse to make it go. We’ve got to go to a horse show next week.’ We have to back up and try to practice quality medicine.”

Loppnow said, “Personally, I work really hard to not just go off of the radiographs or the imaging, but to correlate that to the horse in front of me. And maybe that’s where you fall into the trap of under-diagnosing the subclinical arthritic horses.

“I had a horse recently that had pastern arthritis, [which] was what we were treating,” Loppnow said. “We used regenerative therapies in that joint. The horse is doing great, but we did some survey radiographs of the carpi on that horse because there’s a little bit of abnormal swelling, and there was some osteophyte proliferation in those joints—but the horse blocked out to the pastern joint. So, if clinically I’m treating what’s causing the lameness, am I missing some of the subclinical stuff that may be causing a problem down the road and missing that opportunity to catch it early?”

Kawcak said for veterinarians who don’t use a lot of CT and MRI, he thinks we are likely under-diagnosing DJD, “especially when you start looking at subchondral lesions, things that can progress post-traumatic OA. And again, similar to the racehorse, I think we’re surprised about how many times a relatively normal-looking joint on radiographs will have fairly substantial changes on MRI or CT. But, at the same time, what does it mean to the horse? Sometimes you see fairly dramatic changes, and it doesn’t mean much to him.”

Kawcak noted that in the next year or two, with new imaging technologies more readily available, he thinks veterinarians will be “a little bit overwhelmed” with the changes that occur in the back and pelvis that “right now are a little bit frustrating to characterize objectively.”

Dabareiner said she gets a lot of horses for second opinions. “The typical barrel horse isn’t performing; it’s not taking the right barrel. And when I see it, what’s been done is hocks and stifles and fetlocks in the rear have all been injected. The horse may have been to one or two veterinarians, and it has not had a thorough exam—meaning a diagnostic nerve block to locate the lameness. I would block the horse out, and it ends up with a high suspensory or a soft tissue injury.

“I agree with [this group] that I’m seeing way too many horses over-treated versus localizing the problem,” she said, citing research she published during her tenure at Texas A&M.

Three of those studies involved Western performance horses (cutting, team roping and barrel racing competitors). Many of those horses were thought to have poor performance issues by their owners, but the horses ended up having lameness issues once diagnostics were undertaken.

These three studies in which Dabareiner was involved were published in JAVMA:

- Lameness and poor performance in horses used for team roping: 118 cases (2000–2003)2

- Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance among horses used for barrel racing: 118 cases (2000–2003)3

- Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance in cutting horses: 200 cases (2007–2015)4

Allen said with the spread of standing CT in the next two or three years he thinks veterinarians will see more DJD. However, he continued, part of those findings will be relevant and part will be irrelevant. He said that over the years in his career as diagnostics have improved, it takes experience to have the ability to say, “That is a change, but that’s just a modeling change and that’s not a big deal.” He said putting those findings in perspective is important.

Ortved added, “I think for the most part, we have really good tools in our toolbox to diagnose horses currently, and we likely will be developing more tools. But the horses need to be seen [by veterinarians] in order for us to use the tools on them.”

The Owner’s Role in Recognizing DJD

A theme that was mentioned several times during this veterinarian meeting was the importance of preventing cartilage and joint problems rather than treating them. Mitchell said he asks clients “What’s it going to cost you to replace this horse?” then adds “Compare that expense to what it would cost to maintain this horse properly.”

He added that his “pitch” to horse owners is that “prevention is way easier than treatment” when it comes to DJD.

Tisher said one problem in addressing lameness issues with horse owners is that “oftentimes they reach out to about everyone else before their veterinarian in response to trying to fix some of the issues—whether they’re large or small, whether they’re performance issues or something that’s quite substantial. The list of professionals or ‘supposed professionals’ that get to weigh in before we get to weigh in is kind of long sometimes. And that is a frustration.

“I’m not saying that the rest of those professionals don’t add to it,” he continued. “It’s the order sometimes that frustrates me, and the opportunity to intervene before there’s been other things that have been done.”

He added that owners often have spent a tremendous amount of money before veterinarians get the opportunity to examine the horse.

White agreed that there are two types of owners: “We have some that, if you listen to them, they can really help you with your diagnosis,” he said. “Others don’t have a clue, and you pretty much have to discard what they say; but it helps if you understand the discipline and you know what questions to ask.”

He hopes that going forward, the second group of horse owners—”if you make them think about what the horse is doing”—will pay more attention to what their horses are telling them.

Allen expressed some frustration with owners who bring in an obviously lame horse and are looking for help. He said when those owners ask him “What can I do?” to help their horses stay sound, he recommends that the average performance horse have a twice-a-year soundness exam with podiatry films used to advise the horse’s farrier. “We can look at the horse, do a complete physical soundness examination … palpate the back, palpate the SI [sacroiliac joint], block things that they need blocked.”

Allen said he tells owners that, “Bringing the horse in twice a year for a lameness exam is what you can do that will undoubtedly prolong this horse’s athletic life. We can detect arthritis early and come up with a rational plan.”

Dabareiner added, “I’m sure we all have the owner that, first thing they do is go to a chiropractor, or they listen to their friends, or they go to the internet.”

Kawcak agreed, adding that even with some very successful trainers and riders, “you look at the horse and wonder how it got to this point.” And he said there are others who think “a training-related issue has got to be a physical ailment of some sort.”

He said veterinarians must ask the right questions to get an understanding for what the significance of the problem is. “I think people are starting to maybe understand where they struggle in managing their horses, and I think in those cases [they are] reaching out more,” said Kawcak.

Loppnow added, “I’ve got to say it’s making me feel a lot better that it’s not just me that the clients are avoiding and going to chiropractors and everybody else first. The fact that it sometimes seems like the veterinarian is the last resort rather than the first opinion is something that’s really challenging to deal with. And I think I often find myself spending about half my time proving what it isn’t before I can actually prove what it is, because they’ve gotten so many other opinions from other people.

“I think everybody has a role in keeping a horse sound and performing well—chiropractors, acupuncturists, massage therapists, whatever alternative therapy you want to use—but you have to figure out what the problem is first, and then bring those other parts on board,” Loppnow added.

Loppnow said his message to owners is consistent: “You know this horse better than anybody else … in terms of how it feels, how it moves, what it’s doing—and I need that perspective from you. So, take note of when it’s not doing what you normally expect it to do. Take note of how that’s changed, what it’s doing differently—because the more time-based information you can give me on when it’s doing things [and] what it’s doing, the better I can diagnose what may be going on.”

Mitchell brought up a paper done by Dr. Sue Dyson in Europe on a group of 57 horses that were presumed to be sound by trainers and owners. Only 14 of the 57 horses were determined to be sound after veterinary examination (see the research).5

Mitchell thinks veterinarians fall short in taking time to talk and listen to owners, whereas massage therapists, chiropractors and others do take time to have conversations. “I think if we spent a little bit more time, we can gain information that will help us do a better examination,” he said.

Ortved thinks that providing targeted education to help clients understand what veterinarians can do is important, not to mention actually teaching them what DJD is.

“I think that’s sometimes where they fall into the trap of this whole idea of maintenance injections, because they have this understanding or they have this perception that if they maintain the joints with staged or serial injections every three, six, nine, whatever months they do, then they’re preventing anything from occurring and that’s the best way to approach it,” said Ortved. “They don’t necessarily have a good understanding of what arthritis is and what that means for a specific joint, and that it’s not a widespread problem that happens in every single joint of the body that’s possibly injectable.

“So, I guess the piece that seems to be missing is that knowledge sharing between our profession and horse owners, trainers and other professions,” concluded Ortved.

Loppnow wrapped it up by stating “I think it’s all about controlling the conversation [with owners]; making sure that we’re setting ourselves up to be the first resource, not the third or fourth resource, with each horse.”

Treatments to Address DJD

Mitchell summarized the group’s feelings that there is no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to DJD treatment.

Items the group said need to be determined prior to treatment are:

- Joint involved

- Is it a high-motion joint?

- Is it a low-motion joint?

- Age of the horse

- Stage of DJD/OA

- Is it a first-time lameness?

- Is it a recurrent lameness without significant radiographic changes?

- Is it an older horse with significant radiographic changes and a degenerative joint?

- Severity of lesion

- Anatomic location of lesion

- Is the horse metabolic?

- What are the current and long-term athletic expectations for the horse?

- Was a treatment tried, and what was the outcome?

- Is the horse ridden/competed year-round or seasonally?

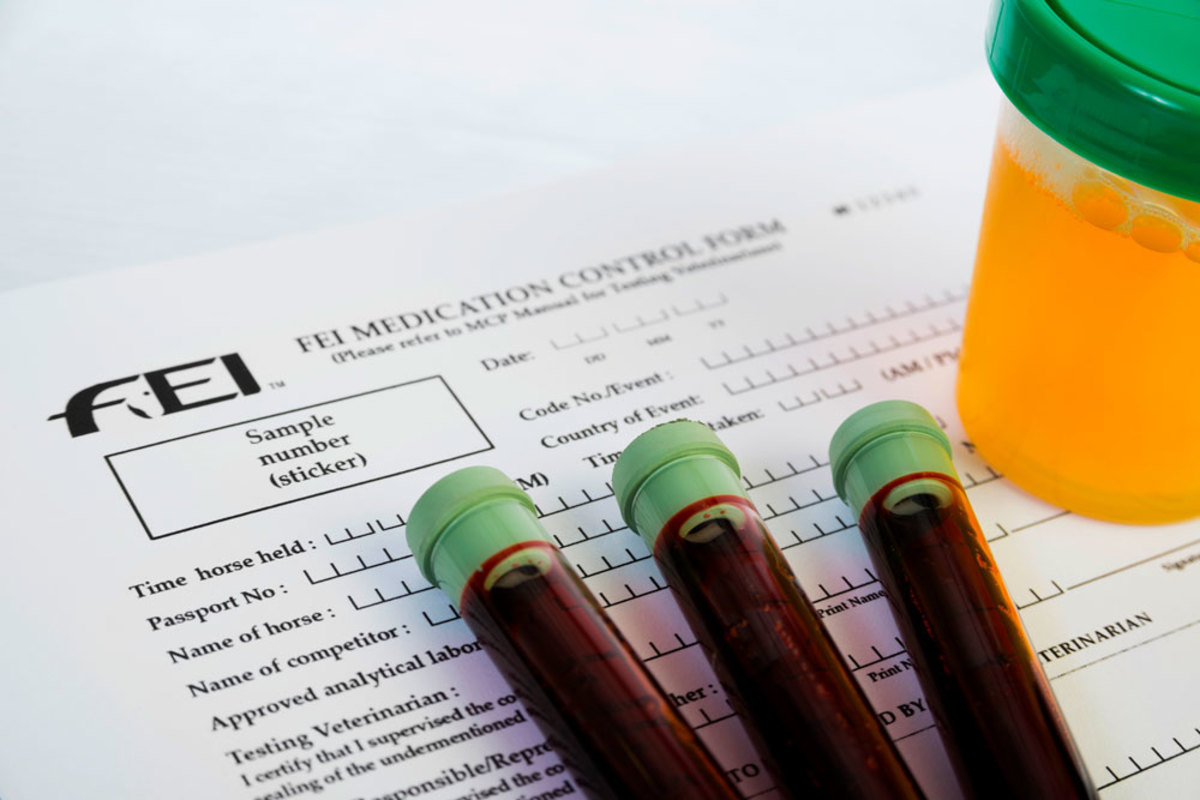

- Are there competition medication guidelines?

- What is the timing to the next show?

- Can the horse be rested?

Treatments used could include:

- Corticosteroids

- Hyaluronic acid (HA) IV or oral

- Adequan® i.m. (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan)

- Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) products

- Regenerative products

- Polyacrylamide gel

- Bute or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Bisphosphonates

- Surgery

- Adjunctive therapies (i.e., shock wave, ice)

- Rest/active rest

White noted that “injecting a horse that needs surgery is not a very effective bandage.”

Tisher voiced what the group members all felt was an issue: oral joint supplements. “The thing I would say that we spend an awful lot of time talking with clients about [is] feed-through oral supplements: the one-million-and-one ‘flex’ products out there that everyone likes to use,” he said.

“They ask about the latest [flex] product that is going to ‘cure everything.’ I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time talking to people about that,” continued Tisher. “I’ve used some products myself, so I feel like perhaps there is a place [for them],” he added. “And, by the way, if you add up what your feed-through costs [are], you may be able to do a box of Adequan i.m. as an FDA-approved product for about half the price that you’re paying for that ‘flex’ product that has somebody famous on the box.”

Allen noted that whatever is used to treat the horse—even if the horse is traveling through and is not staying with you—he cautions owners or trainers to recheck the horse. “Because you have to determine whether or not what you placed in that joint made a difference,” stated Allen. “If it didn’t make a difference, the process needs to be rethought and another product utilized. But you can’t determine that unless there is an objective reality check somewhere along the way. And I try to make it about 30 days.”

As far as joint injections go, Dabareiner said she has decreased the amount of steroid—regardless of what corticosteroid it is—in the joints. “And I don’t see a difference as far as response. I know Chris [Kawcak] has done some work on it, but I think using more is not better with corticosteroids in joints.”

A research project she did at Texas A&M that was not published looked at a group of 50 horses that were diagnosed with distal hock joint pain or arthritis. They did radiographs on them all at day zero, three months, and a year. The horses were randomly assigned to three treatment groups and all groups had similar disease severity score. Dr. Dabareiner was blinded to treatment group when medicating the horses. One group was treated with HA and Depo-Medrol; the other was HA only; and the third group was Depo only. The horses received lameness exams at three months, six months and 12 months, and all were radiographed.

“The conclusion of the study was that horses that were injected with HA and Depo overall stayed [sounder] longer—two and a half months longer—than either one of the other groups,” Dabareiner said. “And there was no significant difference in radiographic changes at three, six or 12 months in any of the groups.

“So, if the client can afford it, regardless of the age of the animal, I try to convince them to put hyaluronic acid even in the lower hock joints,” concluded Dabareiner.

Kawcak said the case that always worries him is the jumper that comes in with acute forelimb lameness, blocks to the heel, and has got some effusion in its coffin joint. “I think most of us have probably had this case, where you inject them with triamcinolone and within weeks—sometimes days—they come up crippled. And we find out on the MRI the horse has been cooking a collateral ligament that you just made worse.

“We’ve done a great deal of research on pretty much everything that’s out there that’s available,” said Kawcak. “And, obviously, we have shown various symptom- and disease-modifying effects of each of them. But at the end of the day, I think, whether you asked me or [Drs.] Dave Frisbie or Wayne Mcllwraith, there’s still that personal approach to it.

“There are areas where I think Depo is far more effective than triamcinolone,” Kawcak continued. “I think there’s a point with some horses that are IRAP’d [receive interleukin receptor antagonist protein or IRAP] continually that maybe the IRAP is not really helping and, in fact, I think in some cases the IRAP might be a little bit detrimental in a kind of a chronic-use situation. There are times where we jump back and forth between steroids and IRAP—or, in our case, a biologic product.

“Sometimes just simply using bute—if you can use bute—in the time that you’re working or pushing the horse might be just as effective,” he said.

He also said that managing the horse with active rest is important, not jumping as much with the older jumpers that know their jobs and working on core strength and stability without pounding joints can be useful.

Loppnow mentioned the issue of using corticosteroid injections and increased laminitis concerns in senior equines. “I pay a lot more attention to the endocrine status of the older horses,” he said.

The veterinarians agreed that while there might be different abilities to pay for diagnoses and treatments among top-level performers, mid-level athletes and backyard/senior horses, veterinarians should “offer the best alternative first, [and] if that’s not workable, find out what is,” summed up White.

White said an “old-timer” veterinarian named Dr. Doyne Hamm often told him, “It doesn’t matter what the people look like or what their horse looks like; offer them the best treatment first. If they don’t want to go with that, then you can find ground where you can go ahead and treat.”

Allen said experience with the medications is a big factor in choosing treatments. “As you do different things and you keep rechecking and questioning your particular view of reality, I think you learn a lot,” he noted.

“I’m in the process of relearning and rethinking how I’ve dealt with backs and necks all these years,” Allen continued. “Before, I just grabbed a bottle of Depo and went merrily on my way, and I helped a lot of horses. Well, since we’ve now switched and started using a lot of PRP in those areas, well, you know what? I’m shocked. I can actually fix some of these horses. Where before, the only question was ‘What’s the interval I need to re-inject?’ Some of these horses, I don’t need to re-inject, or it lasts a really long time. I was not expecting that.

“Like I say, ‘Question your version of reality because it may not be correct.’ That’s why I still get a kick out of doing this at this age; horses debase me of my view of how intelligent I am on a daily basis,” Allen concluded.

Dabareiner said that sometimes veterinarians forget about the simple things, especially with the older horse that’s been through the ringer and now is just asked to tote around a little kid for a playday or teach someone how to ride.

“Those horses have hock issues, stifle issues, maybe a knee, and coffin joints,” she said. “And it’s just not efficient to inject multiple joints on an older horse like that. I think some of those tough old horses just need a little daily bute. I’ve had horses that have been on a gram of bute for years, and they can still go out there and do their job. And I strongly encourage the use of Adequan [i.m.] and have been impressed with the treatment response. Just don’t look at their X-rays; just look at the horse.”

Loppnow brought the perspective of a recent vet school graduate to the group. “I’ve still got the university training on the one side and the private practice experience on the other side that are sometimes in conflict with each other.”

Loppnow added that younger veterinarians sometimes don’t have the “equity” with the clients that older practitioners do. “I work in a practice with doctors that have been there for 25-30 years,” he explained. He said his more experienced colleagues have more leeway with clients to the point where, if they don’t get the lameness resolved on the first treatment or they want to use an additional treatment such as shock wave, they have the equity with the clients to do that.

“Whereas I think the feeling as a young practitioner is I don’t necessarily have that opportunity,” Loppnow said. “The mentality can be, ‘I’ve got to hit on this treatment right now, so that they believe I know what I’m doing and they don’t want to go back to a different practitioner because they’re not seeing the immediate results.’

“The temptation often is to fall back on the corticosteroid injections—the heavy hitters that are going to see impact right away—so that those clients see it as something that’s being effective for their horse,” he continued. “I don’t want to say so they believe in you, but that’s part of it.”

He said young practitioners want clients to believe in them. “I may not have the window of time with those clients to use other modalities that I think are just as effective, but [that] may not provide those immediate snapshot results,” Loppnow said.

Some horses in Loppnow’s Minnesota practice are only seasonally ridden. That means veterinarians need to determine what treatments could be done in the fall versus before active riding/competition season begins in the spring/early summer.

As far as treatments in Mitchell’s practice go, he said, “We’re certainly seeing more and more horses that are 15 years of age and older that are still really working. So, we’re seeing more of those horses that potentially have insulin dysregulation of one sort or another, or have PPID, or they have a metabolic condition. They may be more prone to laminitis.

“For those horses, I strongly recommend the regenerative products, and I stay away from corticosteroids altogether if I can convince a client of the importance of it,” Mitchell continued. “Obviously, we’ve tried to help those horses metabolically already, but it helps me sleep at night when I inject the hocks on an 18-year-old, fat Welsh-cross pony with a regenerative product versus a corticosteroid.

“We’ve got a lot of horses that are just really pleasure horses that get a course of Adequan [i.m.] once a quarter,” he noted. “They’re happy to do it because they perceive that the horses really do benefit from it.”

Allen was quick to add, “I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention discipline medication rules, because that’s a major thing in choosing treatments. Adequan i.m. and Legend are universally accepted across all disciplines, even FEI. Where an NSAID like firocoxib, on the other hand, gets a little misused by clients. Because again, at the regular dose, it takes three days to ramp up to steady state. So, if they’re actually trying to give it to a horse for a couple of days to make them feel better after an event … bute and flunixin would be a better choice just for a couple of days.

“Then, additionally, because firocoxib does achieve stasis, it hangs around a lot longer,” Allen noted. “So, it’s maybe not the best choice for an FEI horse who’s going to competitions every 10 days or so.”

Mitchell added that adjuvant therapies (such as shock wave therapy) also can be used with these horses, and those modalities also have regulations depending on the regulatory body of the competition.

In addition, Tisher mentioned that there are other topical things, such as icing, that can be used as a management tool for these horses.

Owner Communication

As was mentioned before, the veterinarians feel they spend a lot of time talking to owners about treatments that are effective and scientifically proven versus oral supplements. They shared some of their conversations and tips on communication since some owners are serious about their use of supplements.

Loppnow said, “The conversation I always have with a client is that ‘I can’t tell you yes or no that it’s going to work for your horse. Some people swear by them. Some people think they don’t work at all. If I’m going to recommend that you spend your money, I want to have some research or solid proof that it’s going to be effective and that I’m not just throwing your money away.’

“When it comes to recommending things that I think are going to be interventional and helpful for these horses, it really falls back on the science for me,” Loppnow continued. “I need things that are going to be provable, things that are going to have concrete results for these clients.

“So I try to incorporate all that in my discussion with them: How am I spending your money? How am I protecting your horse? How am I going to have some effectiveness with what I’m doing to help treat the issues that are going forward? And acknowledging, too, that there’s a wide range of other things outside of those three questions that may play a role,” he said.

Mitchell said he tries to go the “educational route” with clients and explain the differences and the chemical similarities of various things. He said he doesn’t recommend many oral joint supplements, but he does “steer people away from the off-brand products that really don’t have clear scientific data at all.”

Ortved said she discusses the science—or lack thereof—of most of the nutraceuticals, as well as the fact there is no regulation on the manufacturing process or ingredients like there is for FDA-approved products like Adequan i.m.

She said there is also the “weird peer pressure to give supplements to your horse. If you don’t give a supplement, you’re a really terrible owner.” She added that the discussion is the same whether it is an oral or an injectable supplement that is not FDA-approved.

Tisher said he feels there is over-supplementation with these oral products, “especially in the fear-based, peer-based world that we live in.”

A couple of the veterinarians mentioned a study where joint supplements were researched to see what was (or wasn’t) in them and in what amounts (“Evaluation of glucosamine levels in commercial equine oral supplements for joints”). Some had no levels of the “active” ingredient and others had 221% of label levels.6

Tisher said he talks with owners about the safety, the quality and the consistency of these non-approved supplements. “Is the bucket you’re buying today really the same thing as the bucket you’re buying tomorrow?” he asks owners.

Tisher also mentioned that in competition horses, with regard to regulatory controls, “we just don’t know what’s in a lot of oral supplements, the nutraceuticals. And you can get jammed up a little bit on testing for different things that are in those products that you may or may not know.”

He added that non-FDA-approved injectable products—mostly those that are called “medical devices”—are a harder subject to discuss with owners. “People think that if it comes in a vial and is injected, that it must be FDA-approved, and it must have a safety margin with it. As a practice, we really steer clear of those products.”

White likes to help owners understand what each class of drugs can do for horses. “I’ll say, ‘This is what the non-steroidals like bute and firocoxib do. This is what corticosteroids do. This is what HAs do, and this is what Adequan [i.m.] does. They all have an important place in what we’re doing.’ I think if you do that, people understand that there are differences. I think that helps both you and them make the choice.”

White added, “I’m going to be a little bit harsher about the oral supplements. I don’t think they work. I base that on both research experience and clinical experience. I tell most of the owners, ‘Use a good quality one and it won’t do any harm, but I’m really not sure that it’s worth the money.’

“You can take what it costs you to feed some of these products and you can buy quite a bit of Adequan [i.m.] or Legend, which we know work,” he said. “Or, as the injectables go, I’ll show them a bottle or a box of Adequan [i.m.] or a box of Legend and I say, ‘Look right here. It has an NADA approved by FDA.’ If it doesn’t say that, I don’t sell it, and I don’t recommend it.”

Mitchell stated that “the Polyglycan thing is a big elephant in the room here. I have never purchased it. I have never used it. I will not. But I still have clients that want to use it.”

Kawcak has been involved in research on numerous joint products. He summarized by saying that “safety and efficacy studies support use of medications and protect end users. Short cuts for use put patients at risk.”

White added, “We often forget that that FDA approval also covers the manufacturing of the drug, so that you know that this is manufactured under optimal conditions.”

Allen said he has three things he communicates to clients on the topic of supplements. “One of them is simply that upper-level eventing riders ask if they aren’t sure of what is in their supplements.” The potential penalties involved for a drug positive at the upper levels are so significant that the riders can’t be too careful.

He said he was given one of the supplements, and he had to look up something in it. “It turned out that it was GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid or GABA) which is banned by almost every regulatory body,” said Allen. “I didn’t even know synthetic GABA existed. We immediately started talking to riders and the manufacturers; then we had a whole slew of positives on it. So, you’ve got to be really careful about what’s in those supplements.”

The second illustrative point Allen uses is this story: “The best American event horse in the ’92 Olympics, I took her to Burghley one time,” recalled Allen. “She goes out and ties up on back then what we called Phase A. She hadn’t even run cross-country. She tied up to the point where I had to give her 20 liters of fluids to get her up off the ground. Then I took her back to the stall, proceeded to give her 125 liters that night. At one point I asked the groom ‘Why don’t you go and get me the supplements that this mare had?’ The groom looked at me and says, ‘You want me to go bring them now?’ I said, ‘Yeah, just go bring them.’ She comes back with a wheelbarrow. This horse is on 24 supplements. I’m going, ‘Well, that’s why the horse was on the ground before it ever got to run cross-country.’ These things have effects, and not all of them are good, particularly in combinations.”

The third way Allen explains treatments and supplements to clients is to give them a scale of 1-10 based on safety and efficacy. “On the low end of the scale would be the oral supplements, because they’ve got to get through the gut and, as supplements, they don’t have to have as much proof that they work. Further up the scale would be intramuscular PSGAG and intravenous HAs that are FDA approved pharmaceuticals to be injected in the horse. The gold standard, at the opposite end of the scale from oral supplements, are intra-articular FDA-approved pharmaceuticals because they are placed directly into the affected joint.

“Look at it as a sliding scale from 1 to 10, then you decide how you want me to spend your money or how you want to spend your money,” Allen said. “And I’m happy to do that, but you need to understand the relative scale.”

Dabareiner said she tells owners “it may cost the same amount to give your horse intramuscular Adequan as it does to supplement with a product that’s not metabolically available or not absorbed.”

While at Texas A&M, Dabareiner was involved in the resveratrol study that Dr. Ashley Watts did. “It was a double-blind study in which horses diagnosed with distal hock OA were fed either a placebo or the resveratrol. There was a slight improvement on recheck in lameness if the horse was on the resveratrol versus placebo. But that’s the only study that I’m aware of comparing an oral supplement vs placebo.7 But still, I try to talk to clients, telling them I feel ‘it’s a bigger bang for your buck if you go with the intramuscular Adequan.’ ”

Kawcak said with oral supplements, “a lot of it’s based on theoretical approach—kind of building up the basic tissue building blocks of whatever it is. I just try to stress to the owner that they’re investing in hopefully strengthening tissues, and maybe that will help prolong athletic use.

“I think the other is, as Gary [White] touched on, and I think it’s important, stressing the importance of FDA approval,” continued Kawcak. “Not only for the safety aspect, but for the efficacy aspect and the manufacturing component. I think most people are unaware of what the FDA actually does to protect the consumer, and once they realize that, a lot of times they start to realize that they’re approved for a reason.”

Use of Adequan® i.m. (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan)

“Adequan i.m. is something that we’ve all used for years, and certainly it has played an important role for the equine athlete,” said Allen. “Adequan i.m. is going to be most effective at managing that horse when it has mild to moderate OA. Identifying that group and identifying them before they get to the severe stage” is important to treatment success, he noted.

Allen said you want to catch these horses relatively early in the DJD process, when treatment is going to be most effective. “You’re going to be able to [help] them. They’re going to be successful at their job, and they’re going to keep doing the job,” said Allen. “And that’s where I’ve focused my efforts on use of Adequan i.m., and I’ve found it very successful.”

Dabareiner said she has issues trying to convince owners to use Adequan i.m. as directed every four days for seven treatments in the muscle. “The vast majority of clients that are on intramuscular Adequan do not follow labeled dosing. And sometimes it can be difficult to convince them to change their ways.”

Kawcak said that Adequan has been around a long time, and it obviously has stood the test of time. “If we want to improve communication around Adequan i.m., I think making sure that the dosing paradigm is communicated clearly [is important] because there’s many people who don’t use it according to the label.”

Loppnow said he would argue that Adequan i.m. is one of the treatments that “is in the running for the best thing you could do for the overall health and well-being of that horse. The fact that Adequan really works not only in that joint where you diagnosed DJD but also to promote joint health and mobility, I think, is a huge benefit of it.”8

Loppnow said the way he communicates to clients about use of Adequan i.m. is that “Adequan really works to fight those early DJD problems before they’re diagnosed. Even if I am not working on specific joints, Adequan is still working on improving their health, potentially delaying me having to come treat more advanced DJD in those joints later.”8

Mitchell said he tells clients, “If you’re going to use the product [Adequan i.m.], use it correctly.”

He said that discipline rules that have enabled veterinarians to use Adequan i.m. and similar products “legally and openly” have been important, because they’re supportive products that have been “a big help to the welfare and to the soundness of our high-level competitive horses.”

At one time, the FEI did not allow the use of those products. “We have seen a perceived difference in the health and welfare and soundness of the horses since we’ve been able to use those products legitimately,” said Mitchell.

Tisher noted that “you asked us in one of the previous questions about the backyard horse, the medium-level horse, and the high-end horse. And my thoughts on Adequan [i.m.] is that it is such a great product to recommend for all three of those groups.

“For the group of backyard horses, that is a reasonably cost-effective way to do a really good job of helping that horse’s joints,” he explained. “The medium performance horse for the same reasons, plus or minus some more intensive intra-articular therapies. And the high-level horse to perhaps take that interval of joint injections and extend it.”

Tisher said that the group had talked about diagnosis and finding out what the problem is before determining what needs to be treated, as well as not over-treating. He thinks that for label-indicated joints, Adequan i.m. can perhaps help with some earlier DJD issues.8 “So we’re not having to perhaps go into as many places later with intra-articular therapies when we’ve included [Adequan i.m.] as part of the horse’s management through its athletic career.”

White said Adequan i.m. is “certainly a cornerstone of my approach to treating DJD … I agree with Kent [Allen] that it is most effective on a mild to moderate synovial inflammation without a lot of radiographic changes. I strongly encourage people to do the seven-dose series and repeat it as needed. I’ve found it to be extremely useful. My clients have found it to be extremely useful. And I’m going to continue to keep it as a cornerstone.”

In discussing Adequan i.m. use in low-level, medium-level and high-level horses, White said, “It should be a no-brainer in the high-end horses, and it’s almost a no-brainer in the lower-end horses because here is an intervention that has a potential to prolong a horse’s career. I get the objection once in a while, ‘Well, this costs a lot.’ And I say, ‘Well, what would it cost you to replace this horse?’”

Ortved said that veterinarians should drive home the narrative “that Adequan [i.m.] truly can be given in a safe manner.”

She added that it makes a lot more sense to be using something like Adequan i.m. that has been tested and has demonstrated efficacy and safety than using other products that have no efficacy or could be actually harmful.

Mitchell agreed with other practitioners who talk to the client about preventative medicine versus what it could cost the owner to replace the horse. “I encourage and try to get my clients that have actively competing or training horses [with] soundness problems to consider Adequan i.m. on a regular basis … The way I pitch it is that … there is clear scientific evidence that this [Adequan i.m.] helps to inhibit the development of cartilage degradation and degenerative joint disease.8 So why wouldn’t you use it?”

Mitchell also said he sees owners more willing to use the Adequan i.m. product because they had previous favorable experiences with other horses and the ease of administration.

While the product must be administered by or used on the order of a veterinarian, Mitchell said “It does not have to be given by the veterinarian every time.” He added that “the relatively low reaction rate if given properly is also very comforting [when] handing the product to someone who may not be the most experienced injection administrator.”

Loppnow said his practice is promoting joint health sooner rather than trying to promote it after the horse already has DJD or osteoarthritis that is causing problems. He wants to have that conversation about using Adequan i.m since it is easy for owners to miss subtle signs in their horses.

Allen added to that, saying, “If you’ve got 10 useful years in this horse’s life as an athlete, and if you can keep it going during that time and not have the year or two or three down, that could be 30% of its athletic lifespan, which is huge.”

White concluded by saying “I think the better we’re able to understand what’s happening in the joint, the better we’re going to be able to develop treatments, or as in the case of Adequan [i.m.], justify that Adequan [i.m.] is still a very useful treatment. And I think the better we understand, the better we treat.”

Take-Home Message

Veterinarians want to do what is in the best, long-term interest of each horse’s health, whether it is a backyard pet, a weekend warrior, top-level sporthorse competitor or elite racetrack athlete. Diagnostics for joint disease are expected to improve tremendously in the next couple of years, primarily due to the proliferation and use of standing CT scanners across the country. With these improving diagnostics should come the ability for veterinarians to intervene in DJD earlier in the disease process and work on slowing or preventing career-limiting or -ending effects.

Extending the useful lifespan of all levels of horses starts with veterinary involvement in the horses’ lives at an early age and continues through the golden years.

Communication of best practices with horse owners on joint issues and treatments is expected to continue to be a battle, especially when owners spend money on unproven oral supplements and injectable products that don’t carry the same safety and efficacy assurances as FDA-approved products.

Even an FDA-approved product such as Adequan i.m. requires communication between veterinarians and owners to ensure the product is being used according to label instructions in order to provide the best outcomes for horses.

The need to educate veterinary students and young veterinarians on proper diagnosis of lameness in horses is critical.

Adequan® i.m. (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan) Safety Information

INDICATIONS

For the intramuscular treatment of non-infectious degenerative and/or traumatic joint dysfunction and associated lameness of the carpal and hock joints in horses.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

There are no known contraindications to the use of intramuscular Polysulfated Glycosaminoglycan. Studies have not been conducted to establish safety in breeding horses. WARNING: Do not use in horses intended for human consumption. Not for use in humans. Keep this and all medications out of the reach of children. CAUTION: Federal law restricts this drug to use by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. For more information and Full Prescribing Information, visit www.adequan.com.

PP-AI-US-0552 01/2021

References

1. USDA. Equine 2015: “Changes in the U.S. Equine Industry, 1998-2015” USDA-APHIS-VS-CEAH-NAHMS. Fort Collins, CO #723.0517

2. Dabareiner RM, Cohen ND, Carter K, Nunn S, Moyer W. Lameness and poor performance in horses used for team roping: 118 cases (2000-2003). JAVMA 2005; 226: 1694-1699.

3. Dabareiner RM, Cohen ND, Carter K, Nunn S, Moyer W. Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance among horses used for barrel racing: 118 cases (2000-2003). JAVMA 2005; 227: 1646-1650.

4. Swor TM, Dabareiner RM, Honnas CM, Cohen ND, Black JB. Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance in cutting horses: 200 cases (2007-2015). JAVMA 2019; 254: 619-625.

5. Dyson S, Greve L. Subjective Gait Assessment of 57 Sports Horses in Normal Work: A Comparison of the Response to Flexion Tests, Movement in Hand, on the Lunge, and Ridden. J Equine Vet Sci 2016; 38: 1-7.

6. Oke S, Habashi AA, Weese JS, Fakhreddin J. Evaluation of glucosamine levels in commercial equine oral supplements for joints. Equine Vet Journal 2006; 38: 93-95.

7. Watts AE, Dabareiner R, Marsh C, Carter GK, Cummings KJ. A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of resveratrol administration in performance horses with lameness localized to the distal tarsal joints. JAVMA 2016; 249: 650-659.

8. Adequan® i.m. Package Insert, Rev 1/19.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #18392](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wp-s3-equimanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/30141455/EDCC-Unbranded-7-scaled-1-768x512.jpeg)

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #18383](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wp-s3-equimanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/30141253/EDCC-Unbranded-29-scaled-1-768x512.jpeg)