Equine veterinary practice is known to be a “physical” job, not unlike jobs in construction, auto mechanics and agricultural work. Injuries are common in all physical professions, as working conditions include hazards on a daily basis. Recent studies have attempted to investigate the danger of equine veterinary practice, and results have been mixed.

The British Equine Veterinary Association (BEVA) reported, following its study in 2014, that being a horse vet in the United Kingdom appeared to carry the highest risk of injury of any civilian occupation in the U.K. The study, commissioned by BEVA and conducted by leading medical professionals at the Institute of Health and Wellbeing and the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Glasgow, prompted BEVA to raise awareness of these risks within the equine industry and to look at ways of making equine veterinary practice safer.

Their results indicated that an equine vet could expect to sustain between seven and eight work-related injuries that impeded him or her from practicing during a 30-year working life.

Participants were asked to describe their worst-ever injuries. Most were described as bruising, fracture and laceration, with the most common site of injury being the leg (29%), followed by the head (23%).

The main cause of injury was a kick with a hind limb (49%), followed by strike with a forelimb (11%) and crush injury (5%). Nearly a quarter of these reported injuries required hospital admission, and notably, 7% resulted in loss of consciousness. 38% of the “worst” injuries occurred when the vet was working with a “pleasure” horse, and most frequently (48% of all responses), the horse handler at the time of injury was the owner or the client.

In 2016, the physical wellness of equine veterinarians was queried during the AVMA AAEP Equine Economic Study. Questions about injuries received during practice revealed that of 764 respondents, 46% had never been injured, 20% had received one injury, 26% two to four injuries, and 5% more than five injuries. Almost half of respondents reported missing no work days, and 37% missed fewer than seven days of work. 159 respondents (21%) required hospitalization, and 194 (25%) required surgery.

In order to explore this aspect of equine practice more thoroughly, a survey was conducted over five days in February 2018. The survey link was posted on the Facebook pages of Women in Equine Practice, Equine Vet2Vet, AAEP New Practitioners, Moms with a DVM, as well as circulated to three Decade One networking groups and the AAEP General Listserv.

A total of 466 respondents completed the 19-question survey. The majority of the respondents added comments to their submissions, and a number volunteered to be interviewed in-depth for this article, as they felt strongly that the topic was very important.

Define ‘Injury’

In order to carefully define “injury,” which was not done in the AVMA AAEP study, the most recent survey began with the statement: “Injury in equine practice is fairly common, as horses are unpredictable. In the following questions, injury is defined as suffering a trauma, puncture, contusion, laceration, strain, fracture, hematoma, etc., that was of sufficient significance that you applied a bandage, ice or other treatment, or took a pharmaceutical compound (e.g., ibuprofen) at least once.”

Not surprisingly, with this definition, 96.6% reported being injured during their work as an equine veterinarian.

Interesting comments posted on the Equine Vet2Vet Facebook page included the observation: “Well, then, if we call every nick and bruise an injury, then we get injured nearly every day. No different than a carpenter, mechanic or any other soul in a physical profession. But we are a tough lot.”

Another posted: “I believe it’s a numbers game. I have escaped bad situations made by bad decisions (i.e., no restraint) with only bruises, but my tibial plateau fracture and knee obliteration happened with a haltered, sedated recipient mare handled by a very capable, million-dollar rider.

“We were both by her head when the feed tractor entered the barn … the mare pawed and knocked the handler one way, pinning me and her foal against the wall, breaking my leg, my hand and her foal’s ribs while the handler was trying to pull her off.”

Missed Work

We asked, “What is the longest amount of time that you missed work due to an injury received during your work as an equine veterinarian?” 51.9% reported that they missed one day or less of work, and 22.4% reported that they missed two to seven days. Twenty-six respondents (5.6%) missed more than 90 days of work for their most serious injuries.

Among the comments offered for this question were: “I went back to work instead of appropriate rest,” “Should have taken a few days on both occasions described in Q1, but too stupid!” and “I should have been off longer, but as the owner and main practitioner at the time, I had no choice but to go back to work with a cast on my leg.”

Others said: “I probably should have taken more, but was not allowed,” “I don’t actually remember how much I missed—it was a head injury, but I was a solo practitioner so I know I went back earlier than I should have” and “I worked injured many, many times.”

Veterinarians posting on Equine Vet- 2Vet said, “On the bright side, we horse vets are well prepared to deal with injuries. I broke my wrist last week (not work-related), but was promptly splinted with sticks and a shorts drawstring by two fine horse vets. And I attribute my adept one-handed skills now to years of training while having one arm up a rear end.”

And: “In my experience, we equine vets don’t define ‘needing a doctor’s attention’ in the same way most people do. How many have continued working on non-displaced fractures? I know I have done so, cheerfully! I also know I am not the only one.”

Still others posted about equine veterinarians’ propensity to self-diagnose and avoid seeking medical advice. One suggested on the Women in Equine Practice page: “Another question to potentially consider: ‘Have you ever been injured but didn’t seek professional treatment when you should have?’ or some such variation on the theme of getting hurt, but powering through when maybe we should just take care of ourselves instead. Many of us are too stubborn for our own good!” And: “How many times have you diagnosed your own injury via X-ray or ultrasound?”

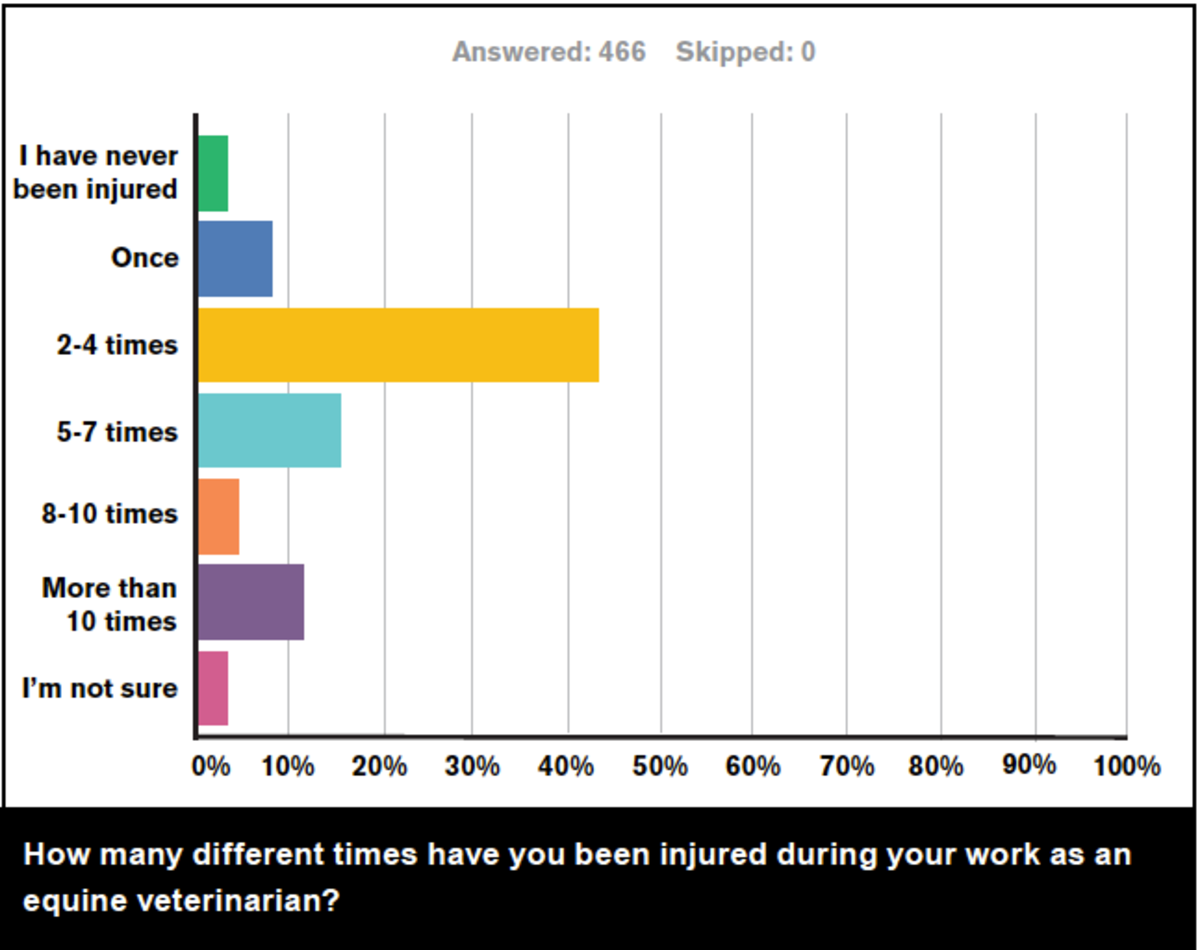

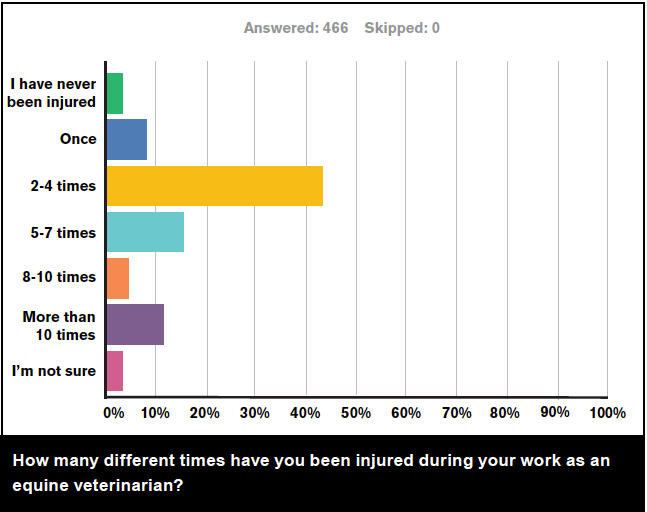

How Often Injured?

The third survey question asked: “How many different times have you been injured during your work as an equine veterinarian?” Almost half (48.5%) of the respondents reported being injured two to four times, and the next most popular answer was five to seven times (17.2%). 12.9% reported being hurt more than 10 times.

Twenty-one of the veterinarians left comments, some of which expressed that they didn’t count small injuries that were considered routine: “Tend to work through the minor injuries and only remember the major ones” and “More than that for fairly minor things (painful, but able to carry on straight away).”

Or they described the injuries they were counting: “Finger bitten, kicked in leg, broken finger, broken wrist.” And: “These constitute minor injuries, contusions, lacerations caused by trauma by horse or associated with horses, some of which should have been brought to the ER but were managed conservatively with good results.”

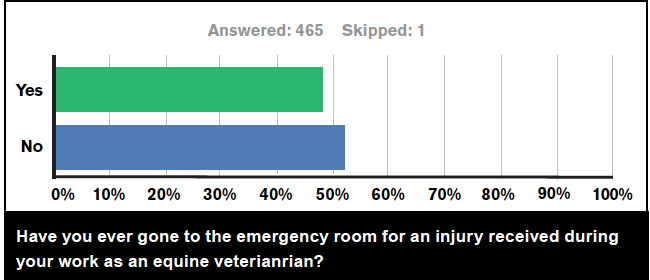

Hospitalization

The survey respondents were next asked whether they had ever been hospitalized or been to the emergency room due to an injury received during their work as equine veterinarians. About a fifth (18.4%) had been hospitalized, and 48% had visited the emergency room.

Of the 39 commenting, one said, “The ER doctor was quite amazed that I brought my own X-rays of the fracture with me.” Another wrote, “Once for laceration at eyelid, two times for the quad hematoma.” Another revealed, “Probably should have, but I have a bad habit of self-treatment.”

Overall, equine veterinarians revealed themselves to be tough and resourceful, often diagnosing and treating themselves and returning to work promptly.

A total of 32.3% of respondents revealed that they had broken a bone from an injury received during their work as an equine veterinarian. Of the 39 comments reporting which bones were fractured, the most commonly reported were ribs, followed by toes and fingers, tibial plateau and facial bones. A shocking 52.2% of respondents reported receiving an injury to their faces or heads during their work as an equine veterinarian. Among the 28 comments, the most common reported injury was a laceration, followed by black eyes and concussions.

Cause of Injury

Getting kicked by a hind limb was reported by 89.3% of respondents and getting struck by a forelimb was reported by 75.5%. Those commenting on being struck (25) revealed that they had been struck multiple times, mostly resulting in bruising, hematoma formation and lacerations. Those that commented on being kicked (11) also reported multiple incidents, and one poor doctor reported that he was kicked “several times, including once cow-kicked directly in the testicles by a mule while standing at least 18 inches forward of his shoulder.”

73% reported being bitten while on the job, but none of those commenting (19) indicated that the bites caused anything more than bruising and minor skin disruption. Being slammed or crushed against a wall was reported by 77.7% of respondents, with only two of 17 comments indicating serious injury— one reported fractured ribs and the other noted that the injury “resulted in chronic SI joint subluxation and vertebral facet injuries.”

Permanent Limitations

Almost a third (30.2%) of respondents reported permanent physical limitations or chronic pain from an injury received during work as an equine veterinarian.

Fifty-two practitioners responded with comments ranging from “After 29 years, there are definitely aches and pains, bone spurs, DJD, etc., but nothing debilitating” to “Chronic back pain from lumbar spinal arthritis and disc disease, arthritis in the knee where I had the tibial plateau fracture.”

Only 10 of the 466 (2.2%) respondents reported being permanently disabled and unable to continue their former level of work as an equine veterinarian from injuries received during their work as an equine veterinarians.

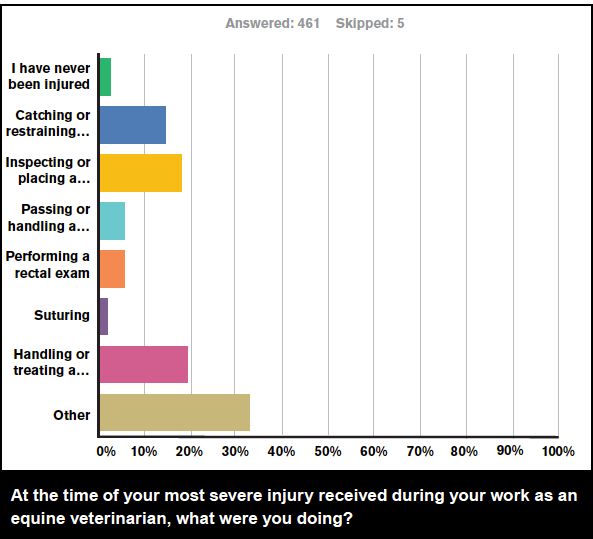

Tasks When Injured

Survey respondents were next asked: “At the time of your most severe injury received during your work as an equine veterinarian, what were you doing?”

About a fifth (19.1%) were handling or treating a limb other than suturing or placing a needle; 17.8% were injecting or placing a needle; 14.5% were catching or restraining a horse, mule or donkey; 5.9% were performing a rectal exam; and 5.7% were passing or handling a nasogastric tube.

The most common response (32.3%) was “Other,” and the 149 comments revealed a broad variety of activities being performed at the time of the injury. The most frequently mentioned included recovery from anesthesia, followed by cleaning a sheath, euthanasia, activities in the horse’s mouth, radiographing neurologic horses and applying a twitch.

About half (45.3%) of respondents reported that at the time of their most severe injury received during work as an equine veterinarian, the patient had received sedation. Multiple respondents also stated in the comment section that the injury occurred while they were attempting to administer sedation.

About a third (33.0%) of respondents revealed that at the time of their worst injury, the patient was restrained by the owner or their agent, and 27.4% reported that the patient was restrained by a veterinary technician or assistant. A farm or barn employee was restraining the patient in 15.3% of cases, and 10.4% of patients were not restrained. 11.5% of respondents chose “Other,” and most of the 53 comments indicated that the respondents themselves were restraining the patient when the injury occurred.

Injury and Experience

The respondents were equitably represented among years from graduation in five-year blocks. However, 52.2% of the worst injuries received during work as an equine veterinarian occurred during the first five years of practice, and 22.6% during years six-10.

One respondent commented, “Although I have not been hurt as badly as many of my fellow equine vets, I fully recognize this is unusual and that ‘my time will come,’ which is scary. I believe that my residency certainly reduced the number of injuries, as I was working with very skilled technicians restraining the animals. We weren’t going to accept any poor behavior from the horses, as we had to protect the students (whereas we likely would have continued working in a bad situation if the students weren’t there).

“Now, after residency, I have been kicked or nearly kicked much more often. Relying on owners to restrain their animals is risky. I am lucky that my clinic is good about allowing us vets to refuse to treat dangerous animals. I have refused clients once or twice, and while I felt guilty doing so, I also know that my career depends on their animals’ behavior.”

Cases in Point

Mary Swartz, DVM, a solo equine practitioner from Oklahoma, has been practicing for nine years. However, she will be transitioning to companion animal practice soon because “I will be crippled at 50 if I keep doing equine work that long—it’s just not sustainable.” Swartz recently tore her meniscus when she twisted away from a horse that stepped on her foot. But her worst injury was a separated shoulder that occurred when a horse she was palpating per rectum squatted in the stocks.

As an ambulatory doctor, she drives about 30,000 miles a year, making the odds much higher of being in an accident. And last year that happened; she was in a serious car wreck but was not badly injured.

Although she is leaving the equine veterinary field, she offered this advice to new equine veterinarians: “If a horse is dangerous, you should walk away. Needle-shy horses are the worst. Remember, it’s not worth getting injured, because if you’re hurt, you can’t help your practice grow.”

The worst injury that Elizabeth Schilling, DVM, suffered during her 26 years (and counting) in equine practice was a head injury. It was sustained when she was attempting to catch the patient, a mare with behavioral problems due to an ovarian tumor, in the stall before the owner arrived. Schilling has no memory of that day, but she was found unconscious by the owner in the stall.

Because she was in solo practice at the time, when she was discharged from the hospital after being unconscious for three days, she returned almost immediately to work. During that time, she had someone else drive and limited her practice somewhat.

She sustained a second serious injury several years later while suturing a wound on a horse’s limb while the horse was held by an amateur. Although the horse was sedated heavily with detomidine and butorphanol, Schilling reported, something caught the horse’s attention and she was kicked in the face and sustained a fractured jaw.

Her advice to prevent injuries is: “Be smart about it. Don’t take chances. Remember that we increase the horse’s threat level—they don’t see us as benign. Always have a good handler and know your limitations.”

Cathy Lombardi, DVM, of Virginia, has been practicing equine medicine for 15 years. She was preparing to inject a sarcoid on the girth line and had already placed her needles. She squatted down by the forelimb to get another look and was “nailed in the face with a roundhouse kick from the hind foot, splitting her forehead open just above the eyebrow.” The patient had been sedated with 10 mg of detomidine and was being held by the owner.

Lombardi went to the emergency room to be sutured and developed two black eyes, but she had no lasting effects except an extra-cautious approach to her work.

Her advice is: “Never fully trust sedation. Have an experienced assistant with you. Realize that nothing is worth getting killed for, and remember: We’re responsible for the patient, the client and our own safety, and we would feel awful if someone got hurt.”

Other Human Injuries

Sometimes it isn’t just the veterinarian who is at risk. Two years ago, sports medicine practitioner Jen Baltrus, DVM, from Arizona, was performing a lameness exam on a large warmblood dressage horse. She was 29 weeks pregnant at that time.

After localizing the lameness, she prepared to block the medial compartment of the stifle. Her technician was holding the horse and a lip chain was applied, as the owner said the horse reacted badly to twitches. From the left side, Baltrus reached across to place the needle. The big horse lunge forward, knocked her technician over, then backed into and kicked the veterinarian twice.

The vet was slammed into a wall, lacerating her elbows and head, and she immediately went into labor. With placental separation, her baby was delivered by emergency C-section at the hospital and was hospitalized in the NICU for two months. Thankfully, the little boy (now 18 months old) survived and is doing well.

Because she is self-employed, Baltrus returned to work just three weeks after her accident. She said, “Returning to work was therapeutic and less stressful than staying at the NICU.” While “there was absolutely no warning” from this patient, Baltrus hasn’t backed off from practice. She said, “There is no other job for me. This is my passion!”

Oklahoma veterinary surgeon Trent Bliss, DVM, has been practicing for 12 years. During his surgery residency, he suffered a subluxated shoulder and torn labrum while recovering a horse from anesthesia. Repair of this injury required two surgeries. Three years ago, while collecting a stallion, he suffered a knee injury that tore his medial collateral ligament off the bone, damaged his ACL and caused a depression fracture of his lateral femoral condyle. Bliss noted, “I don’t know how I’m going to make it to the finish line!”

He lamented that attracting veterinarians to equine practice was difficult because “the physicality of the job of an equine practitioner, in conjunction with the stress and hours, are not commensurate with the wages—especially when compared to companion animal practice.”

After 28 years of clinical practice, Barbara Crabbe, DVM, has experienced a lot of minor injuries, but she was not prepared for the speed with which her most serious work injury occurred. She was finishing up flushing an abscess on a 20+-year-old Quarter Horse mare. The horse was well-sedated and twitched at the time, but it suddenly struck out without warning, hitting Crabbe forcefully in the shin.

Despite the fact that her Levis were not torn, a deep laceration extended from just below her knee to the ankle, with the tibia completely exposed. The result was an ambulance ride, three days of hospitalization and two surgeries to repair the laceration. She reported, “I was extremely lucky—if she had gotten my knee or ankle joint, or broken my tibia, it would have been much worse. And if she had gotten my abdomen/chest/head, I would probably be dead. It was a good wake-up call. As it was, I was back at work a little over a week after coming home from the hospital, with light duty for a bit.”

New Bolton Center Field Service veterinarian Liz Arbittier, VMD, was seriously injured in her 16th year in practice. “It was a wake-up call,” she said. Arbittier was attending to a needle-shy mare with a large shoulder laceration.

The owner was holding the mare, which was restrained with a lip chain as well as a twitch and was sedated with 10 mg of detomidine and 10 mg of butorphanol. The veterinarian was standing at the point of her shoulder and had just begun to clip the area of the wound. The mare stomped her front foot and nearly fell over. Arbittier waited a moment— then, without touching the mare, turned the clippers back on. Like a flash, the mare cow-kicked and ruptured the doctor’s quadriceps. The injury was very painful and caused a non-weight bearing lameness for months. Fortunately, although she has adhesions, no permanent disability occurred.

Arbittier’s advice is: “You can get hurt doing something routine, when you have taken all the steps to stay safe. Remember not to take chances; nothing should trump your safety and well-being!”

Reporting Injuries

When you are injured at work, it is important to report your injury promptly to your employer if you are an associate. Workers’ compensation insurance might pay for your medical care, rehabilitation, salary replacement for lost work time and permanent disability benefits if you don’t recover fully. To get these benefits, you must file a claim and follow your state’s procedures carefully. Generally, your employer will provide forms for you to fill out, and the employer will submit those forms to the insurance company.

If you are seriously injured, always get immediate emergency medical care. However, be aware that except for emergency treatment, some states require you to go to a treating doctor or medical provider network that your employer has designated. State laws vary on the details of workers’ compensation claims, so be sure to explore this carefully. You can find specifics for your state at www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/ free-books/employee-rights-book/ chapter12-5.html.

Young Veterinarian Injury

Because the majority (52.2%) of serious injuries reported in this study occurred during the first five years of practice, it is important to consider why that could be the case. Perhaps new graduates feel obligated to prove that they are able to “get the job done.” If they have been around horses all their lives, they might have a degree of overconfidence and forget that veterinarians often perform uncomfortable or outright painful procedures that elicit fear and aggression in patients.

Some of the injured reported that they were the one restraining the patient when the injury occurred. While this is understandable if the available help is inadequate, no doubt it is a contributing factor. Those with equine experience might feel they are invincible.

Equine veterinarians with less horse experience might simply lack the ability to “read” horses and miss subtle signs of an impending “blow-up.” Some young veterinarians might feel pressure from their employers to never refuse to work on a horse. They also might feel guilty if they are afraid, and they could get into dangerous situations as a result.

Some advice from respondents on how to stay safe included: “It’s not our job to train badly behaved horses.” And: “If the horse is dangerous, walk away!”

Another explained, “There’s a lot of pressure on new veterinarians to put themselves in unsafe positions to get the job done, but later, with more experience, you realize it’s not worth getting killed for.”

Many respondents indicated that associates need to advocate for themselves and make their own safety a priority.

Solo Practitioner Concerns

Because about 40% of equine practitioners are in solo practice, unless they return to work swiftly after injury, they risk losing clients and essential income. Comments made by respondents to this survey made it clear that returning to work against medical advice was the norm.

While it is important for all veterinarians, disability insurance is essential for the self-employed. If you are able to save enough money for at least 90 days of living expenses in an emergency fund, purchasing a policy with a 90-day waiting period is sensible. However, most ambulatory veterinarians working alone should pay the premiums for a much shorter waiting period.

Take-Home Message

Equine veterinary practice is a physical job that involves large, unpredictable, powerful animals. Some injuries are inevitable, but careful use of sedation, knowledgeable assistants, appropriate restraint methods and caution can minimize accidents.

Refrain from taking responsibility for training a badly behaved horse. Be willing to walk away from danger, and pay close attention to controlling the environment where you are working in order to keep you, your patient and those around you safe.