Ambulatory veterinarians filled the room at the AAEP Summer Focus Meeting June 25-27 in Raleigh, North Carolina. They were nourished with experience-based strategies for managing profitable mobile practices.

The meeting had two tracks, one of which was Field Skills for Road Warriors. The content for this section included practical business topics along with tips on treating an assortment of medical conditions that are commonly encountered in the field. Attendees had a wide variety of experiences and divergent practice focuses, but they all seemed to find nuggets of take-home, put-it-to-use information.

There was an additional day of wet labs held at North Carolina State University’s vet school to provide hands-on practice for respiratory, ophthalmology, reproduction and lameness skills.

Editor’s note: A big “thank-you” goes out to Boehringer Ingelheim for bringing this information to you.

Practitioner Resilience

Jeannine L. Moga, MA, MSW, LCSW, of North Carolina State University, admitted it was unusual to find a social worker in a veterinary college. She originally was hired to help veterinarians work better with clients, but now she spends most of her time working with veterinarians on occupational health and resilience.

In her talk “Building Practitioner Health, Wellness and Resilience,” Moga said research has moved away from using the term “stress management” and now focuses on “stress resilience.”

“We can’t eliminate all sources of stress, so we need to build shock absorbers and learn to bounce back” from stress, she said. “We get stronger every time we meet a challenge successfully.”

Moga said that resilience is the core strength that enables us to withstand, bounce back, pre-empt and even prevent stress without developing stress-related complications. She noted that the unpredictable nature of ambulatory practice makes learning to handle these stressors particularly important if we want to maintain our well-being and our capacity for high-quality care.

“Recent research in neuropsychology indicated that stress resilience is highly dependent on cognitive, emotional and social resources that can be employed to counteract the complications of chronic stress,” she said.

Stress is a physical problem, Moga noted. “Chronic stress is a neurodegenerative disorder involving the sympathetic nervous system dominance. There is a decrease in functioning of the prefrontal cortex and significant aging of telomeres,” she noted.

Understanding and working with your brain is the key to building stress resilience. “The brain’s evolutionary function is to discern and respond to danger, not to create happiness and contentment,” she said. “The brain has no pain fibers, so signals overload via fatigue, distraction and mood disruption. However, neuroplasticity ensures that new neural pathways can be built through behavior, thought, emotional activation and environmental stimuli.”

The brain, with or without stress, has two modes: “default” and “focused.”

Characteristics of the default mode include:

- mind wandering

- spontaneous thoughts

- often involves negative or neutral thoughts undirected and sometimes superficial thoughts

- deactivation with mentally demanding tasks

Characteristics of the focused mode include:

- undistracted presence

- immersion

- “flow” (see below)

- often being goal-directed

- can be externally or internally focused

- can be triggered by novelty and meaning

“We spend two-thirds of our time in default mode,” said Moga. This is the brain state most associated with depression, anxiety and cognitive deterioration. Stress resilience is found in the focused mode.

How do we work on switching to focused mode? One way is by encouraging the state of “flow” that was mentioned above. “Flow is when you are so immersed in what you are doing that you lose track of time and space,” explained Moga. “It is usually triggered by novelty and meaning.”

She said that we need to spend about two-thirds of our time in focused mode because when we are in that mode, we can’t be stressed out. “We are so relaxed that we can’t trigger the sympathetic system,” she said. “Unfortunately, we spend most of our waking time feeling distracted and dissatisfied,” she added.

Humans tend to:

- habituate to good things (both pleasure and happiness decrease over time);

- overestimate future pleasure (so we ignore what is good right now);

- multi-task (Americans have an average of 150 undone tasks in their subconscious awareness);

- devote abundant cognitive energy to “rehashing and rehearsing,” also known as ruminative thinking.

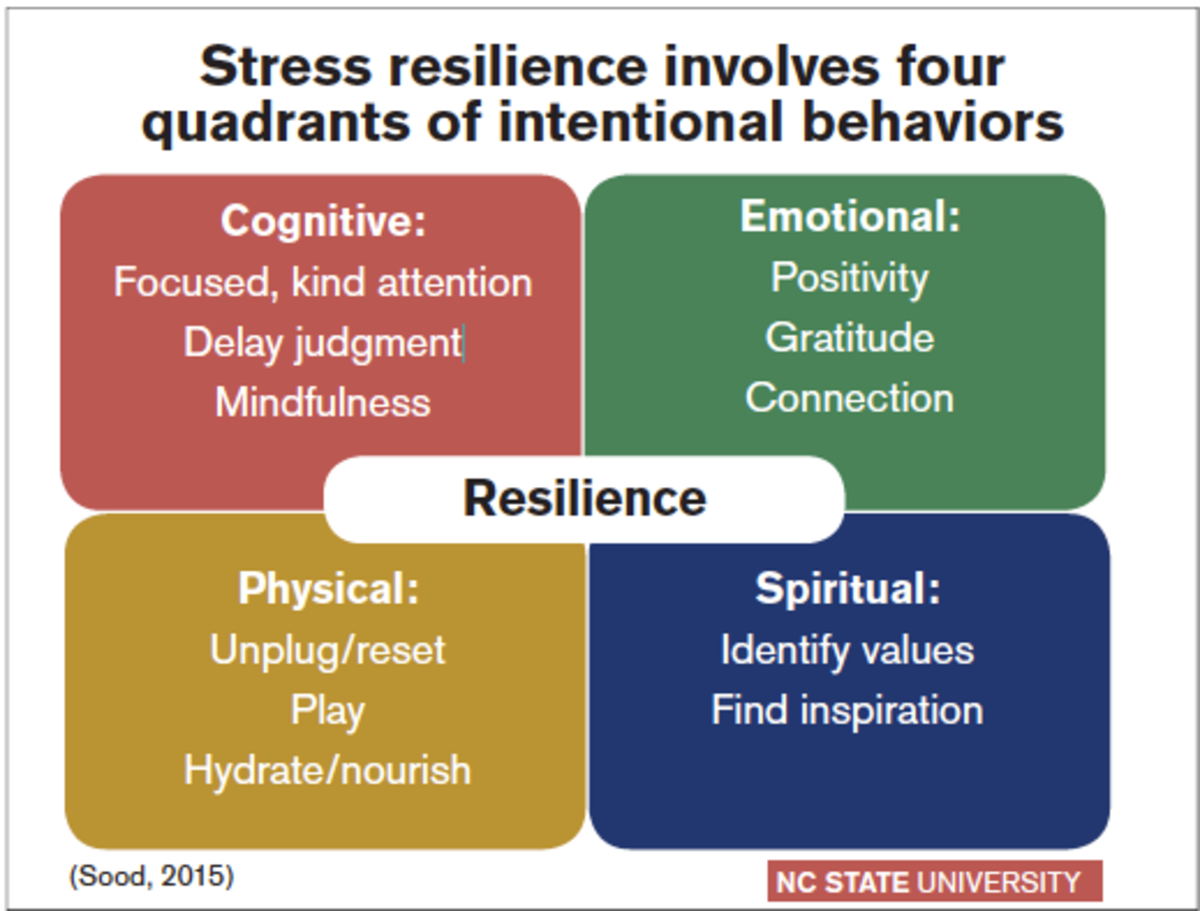

Developing stress resilience requires attention to four quadrants of behavior: cognitive, emotional, physical and spiritual.

Cognitive: One suggestion from Moga to improve cognitive behaviors was to intentionally focus your attention during the first two minutes of any situation or interaction to look and listen for what is new, interesting and meaningful. “Doing this successfully often requires that we suspend judgment,” Moga explained.

She also recommended that you limit worry time. If you or a client are worried about something, set a timer and worry for 10 minutes. “If you are going to do it, do it right,” she said. Then when the timer goes off, you stop. “We need to compartmentalize to cope,” Moga noted.

Another cognitive tool is to trigger novelty, interest and meaning. She used the acronym FOND 5-4-3-2-1 to help you remember. Find one new detail (FOND) and go through your five senses to take note of five things you can feel, four things you can smell, etc.

Emotional: In the emotional quadrant, Moga suggested that you can create a daily practice of remembering positive things that happened. “Positive thinking, as well as gratitude, have been scientifically shown to amplify emotional resilience,” she noted.

Emotional tools that you can use include:

- Cultivate positive thoughts (three positive thoughts to one negative).

- Express gratitude regularly.

- Keep a “happy file” to counteract the negativity bias.

- Cultivate connections with colleagues.

Why do these things? “Positivity improves flexibility, innovation, decision- making and resilience,” she said. “Gratitude builds positivity and resource building, and social support moderates stress, improves appraisal and reduces burnout.”

Physical: In the physical quadrant, remember that it is important to care for the body in order to care for the mind. She said that slow, deep breathing helps to manage the physiological stress response by triggering the parasympathetic nervous system and getting the higher brain “online.” Moga said that additionally, movement and exercise are critical for discharging stress-related negative energy.

Physical tools that you can use for restoring balance include:

- Use technology wisely.

- Exercise to reverse the shortening of telomeres.

- Hydrate and refuel wisely.

- Breathe.

Moga noted that technology overstimulates the brain and makes it difficult to rest/relax. She also pointed out that aerobic exercise reverses the shortening of telomeres. “Water and glucose are required for optimal cognitive functioning,” she reminded.

What can happen if you don’t take care of yourself? “Decision fatigue can set in by 10 a.m.”

Spiritual: Finally, the key spiritual tool is a sense of purpose and service based on your values. “By intentionally living and working in alignment with your values, your ability to tolerate pain and cultivate resilience will grow,” she said. Spiritual tools that you can use to cultivate meaning in your life include:

- Identify your core values and maximize them.

- Maintain a link between your daily work, your sense of purpose and your best skills.

- Remember who and what inspires you.

“Self-care should be thought of as part of our oath to do no harm,” Moga said. She added that resilience-building behaviors are the responsibility of each practitioner, because improved health and well-being translate to healthier practices and better medicine. “Remember,” Moga said, “you can’t serve from an empty vessel.”

Some resources that Moga listed were: Stressfree.org, Positivityratio.com and Gratefulness.org. She also recommended these apps: Calm, Headspace and 8 Fit (a physical fitness app).

Review of Laceration Repair and Acute Wound Management

Timo Prange, Dr. med. vet., MS, DACVS, who is a surgeon at North Carolina State University’s vet school, noted, “A thorough initial examination of a wound followed by appropriate and aggressive treatment—especially in the early phases of wound healing—increases the chance for a fast recovery and a satisfactory outcome.”

He discussed his method of taking a history on the horse, restraint, controlling bleeding and exploration of the wound. A couple of his recommendations from this section included avoiding well water for cleaning wounds and using wet gauze sponges or KY Jelly to keep hair out of wounds when you are clipping around them.

Prange noted that the earlier a wound is treated, the better the chances are for a successful outcome. “Veterinarians have the greatest impact on the early phases of wound healing (hemostasis and acute inflammation), where proper surgical debridement and wound irrigation, in combination with adequate hemostasis and good drainage, can support faster healing.”

Field Endoscopy

Callie Fogle, DVM, DACVS, of the North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine, gave an informative presentation on field endoscopy of the upper respiratory system accompanied by short, how-to videos that enabled the practitioners to visualize the structures and procedures she discussed.

“Recognizing normal anatomy and developing a systematic approach to a complete evaluation of each portion of the upper respiratory tract are essential for accomplishing a successful examination,” she noted. “A complete field endoscopic evaluation should also enable the veterinarian to identify the subset of horses that can benefit from dynamic upper respiratory evaluation. Horses that have normal resting examinations or subtle abnormalities on resting examination may have significant exacerbation of disease or dysfunction under exercising conditions, which can help provide a more definitive diagnosis.”

Among the tips she gave was to consider sampling with endoscopic biopsy forceps or using the endoscope to guide sampling with endometrial biopsy forceps. She discussed the importance of cleaning and leak-testing the endoscope after each use. After use on horses with potential infectious disease, the endoscope should be sterilized.

In summary, Fogle reminded veterinarians to look carefully at each segment of the upper respiratory tract, take care of equipment, know what normal looks like and consider taking samples during examinations when indicated.

Lameness Exams in Ambulatory Practice

Rick Mitchell, DVM, MRCVS, DACVSMR, Certified ISELP, of Fairfield Equine Associates in Connecticut, noted that a thorough and efficient lameness exam can be a major practice builder. His presentation was filled with short video clips that allowed the audience to see the types of lameness cases that Mitchell discussed.

“Today’s technology allows the ambulatory practitioner to have a great deal of sophisticated diagnostic equipment at his or her fingertips, including portable digital radiography, diagnostic ultrasound and even commercial objective lameness detection devices,” said Mitchell.

He stated that he thought a qualified vet tech was a good investment. “A veterinary technician can make the process of lameness diagnostics much more efficient and accurate, as well as professionally fulfilling,” he said. “They also ‘have your back’ when you have a difficult horse, so you can get through an exam efficiently and safely.”

Mitchell said that having good, portable imaging equipment is essential to making on-the-spot diagnoses and for client satisfaction. He said it is a logical investment, and you can calculate the return on investment (ROI) fairly easily. “You can get an excellent rate of return on your investment if you do significant lameness exams. If the equipment is easy to use, you will use it. If it is antiquated or heavy, you won’t use it as much.

“I encourage you to engage your client when you are doing the exam,” he added. “It’s a great practice builder.”

Mitchell said you should start by watching the horse in his stall. Then you need to be prepared for not only a visual and hands-on examination out of the stall, but to watch the horse go in-hand while moving at various gaits, over various footing and using different patterns (circles, serpentines, backing, etc.). He also noted that some horses only show a lameness problem when ridden.

Since Mitchell is trained in acupuncture, he uses a modified hands-on exam that utilizes acupoints. “An obvious lameness may be easy to elucidate, but a more subtle lameness may require an extensive exam,” he explained.

Mitchell will remove shoes for diagnostic radiographs other than foot balance images, and he will manipulate limbs and use hoof testers before he asks for the horse to be walked or jogged.

If there is a performance complaint, but no real lameness was demonstrated with manual palpation and in-hand examination, Mitchell will ask to see the horse perform. This might be jumping or lateral work. “Disturbed performance or disobedience may be evident in cases of neck-, back- or sacroiliac-related discomfort,” said Mitchell. “Some organic issues, such as gastric ulcers, may cause similar behavior when the horse is worked under saddle, which may mimic a sore back.”

He added that observing a riding exam might require a veterinarian to get training and experience in observing horses under saddle. “That often changes the horse’s way of going, which may be useful in locating the origin of discomfort,” said Mitchell.

“Observe the horse at a sitting and rising trot, and at the rising trot with the rider on the wrong diagonal,” Mitchell said. He noted that changes of diagonal or the rider posting on the wrong diagonal might accentuate the lameness.

There are other tools that veterinarians can use, including nerve blocks. Mitchell warned that severely lame horses might be at risk of more damage due to structural instability if the animal is desensitized and exercised.

Mitchell said at this point the practitioner should have a good idea of the area or areas in question that need to be examined by radiograph or ultrasound. “Keep in mind that a thorough examination provides value, and there is nothing unprofessional about charging appropriately for time spent,” stated Mitchell.

He noted that there could be liability in asking someone to ride horse that is lame. “That must be agreed upon between you and rider,” he stated. “Also, I don’t let anyone get on horse without a helmet. Safety is important.”

Mitchell said that a horse working at a canter under saddle might show different clinical signs of lameness than it did when lunged at the canter. “You could see a stabbing, foreshortened gait indicating a possible stifle or hock problem, or lead-swapping, crow-hopping or bucking indicating lumbosacral or sacroiliac pain,” he noted.

Mitchell also advised the audience to look for saddle slip, which might be evident in horses with subtle hind limb lameness. “The saddle will slip toward the side with the affected limb,” he said. You can repeat Flexion tests with a rider aboard, which might reveal further evidence of lameness, said Mitchell.

In response to a question from the audience, Mitchell said he prefers to have the horse’s regular rider aboard, but if that person isn’t available, he wants a good, quiet rider. That holds true for English or Western horses.

Mitchell added that a bone scan might be useful when radiographic findings are inconclusive. “Scintigraphy is useful for regionalization of a problem,” he said.

When should a practitioner look to MRI? Mitchell said that if there are negative or questionable radiographic results, with suspicious or negative ultrasound findings, then it might be time to look at an MRI.

“Keep in mind that disturbed performance may be seen in cases of axial and appendicular musculoskeletal pain, but organic issues such as EGUS may cause misbehavior and mimic lameness,” he advised.

A practitioner in the audience asked whether Mitchell saw primary SI pain. “I think SI pain is a common occurrence in dressage, show jumping and reining horses,” he replied. “There are two kinds of SI pain: primary and secondary. It can be primary, but more often it is secondary pain due to distal limb lameness and asymmetrical carriage. The horse will ‘work into’ an SI problem because of other low-grade problems.

“I find that a distal limb problem Comes first, then SI,” he said. “Some horses can develop SI pain from athletic effort or getting cast.

Editor’s note: A big “thank-you” goes out to Boehringer Ingelheim for bringing this information to you.