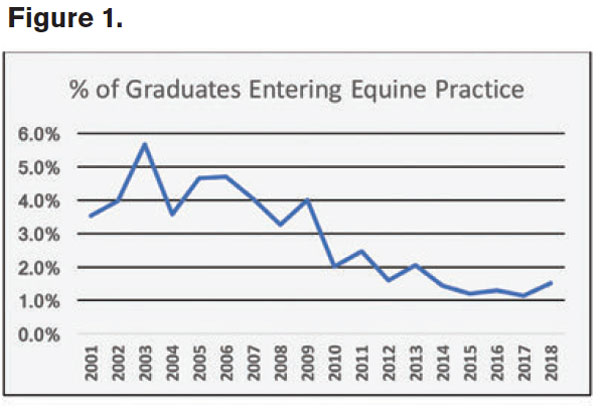

The recently released 2016 AVMA AAEP Equine Economic Survey Report showed that more than 50% of recent graduates have failed to renew their AAEP membership within five years following their graduation. In addition, the number of new graduates that are choosing equine practice has dropped from 5.7% in 2003 to 1.1% in 2017 and 1.5% in 2018, according to AVMA data (see Figure 1). An effort was launched to determine the reasons for this trend.

An eight-question survey link utilizing Survey Monkey was distributed on several Facebook sites in May 2019. The sites utilized were the closed groups Women in Equine Practice, Equine Vet- 2-Vet, Moms with a DVM, and AAEP Member Vet Talk. The survey was open for about 10 days, and 647 veterinarians responded.

Questions included the percentage of equine work done by the practitioner, the year of graduation from veterinary school, whether the respondent was an associate or an owner, and the size of the practice.

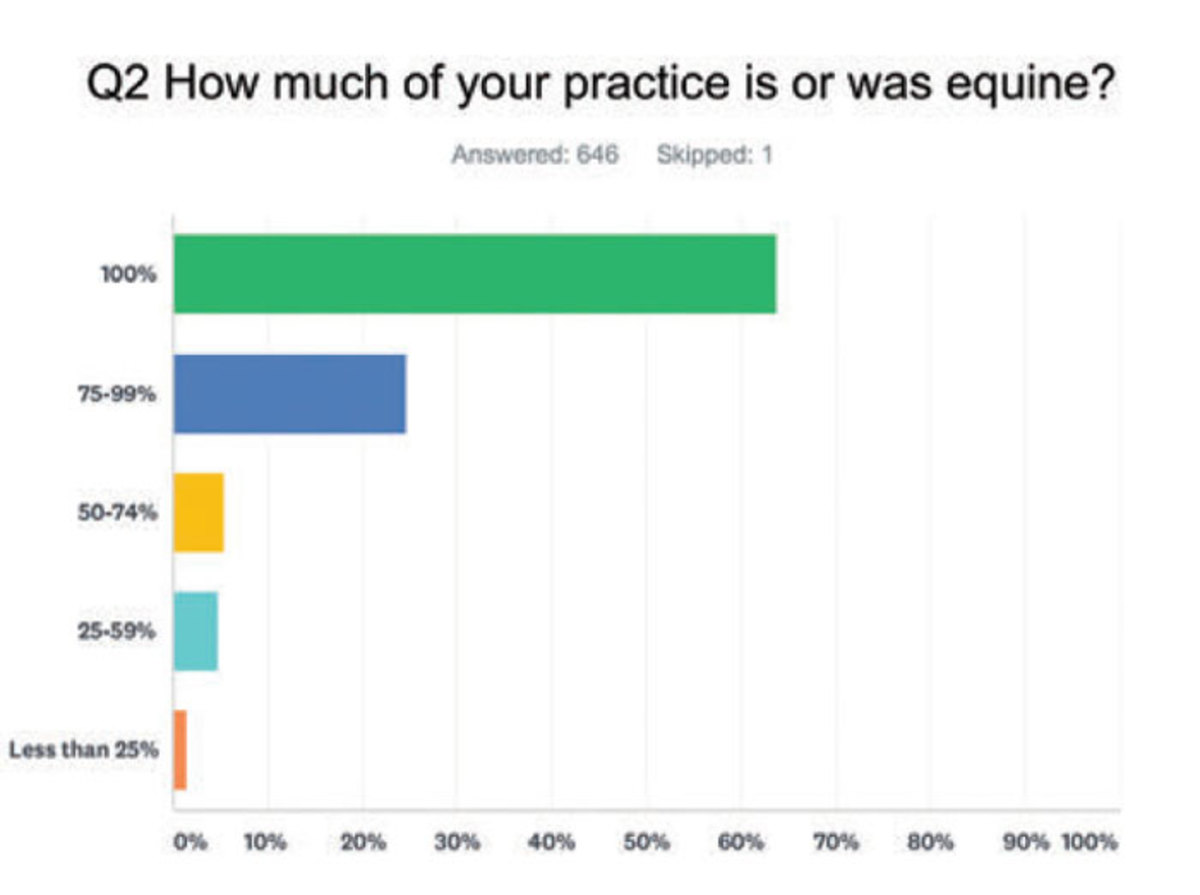

All of the questions allowed the veterinarians to write comments, and they wrote many to explain their decisions. The questions asked the doctors to answer based on the equine practice where they were currently working or where they had previously worked before leaving the career. The majority of the respondents (63.8%) reported that they were currently or had formerly been at a 100% equine practice, followed by 24.6% that reported their practice was 75%- 99% equine (see Figure 2).

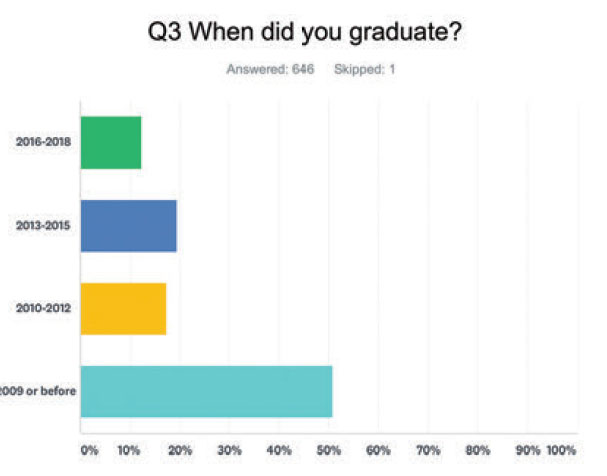

Because the phenomenon of attrition of equine graduates from AAEP membership showed an increasing trend from 2000 onward, the survey broke the respondent cohort into fairly small groups in order to see whether there were differing or worsening trends among different graduation years.

Those graduating 10 years or more ago were grouped together, while the most recent decade was grouped in three-year increments. As might be expected, the majority (50.8%) of respondents graduated in 2009 or prior to that. The most recent decade was well represented in each of the three segments of graduation years (see Figure 3).

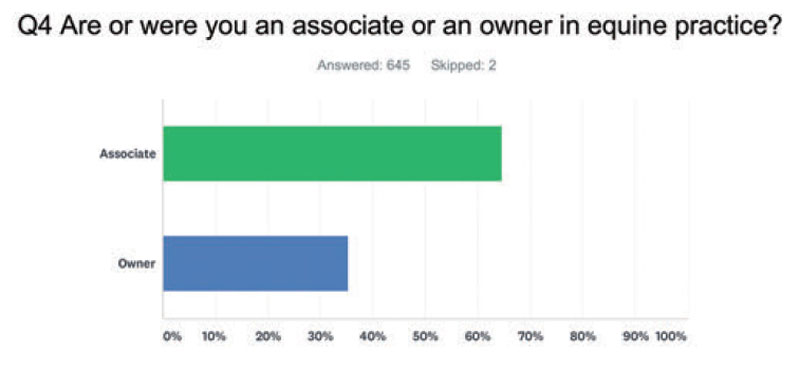

Most likely due to about half of respondents graduating in the last decade, associates (64.6%) outnumbered owners (35.4%) overall.

When looking at just those who graduated in the last decade, 80.6% identified themselves as associates and 19.4% as owners. This is in contrast to those graduating in 2009 or before, of whom 49% reported they were associates and 51% reported they were practice owners (see Figure 4).

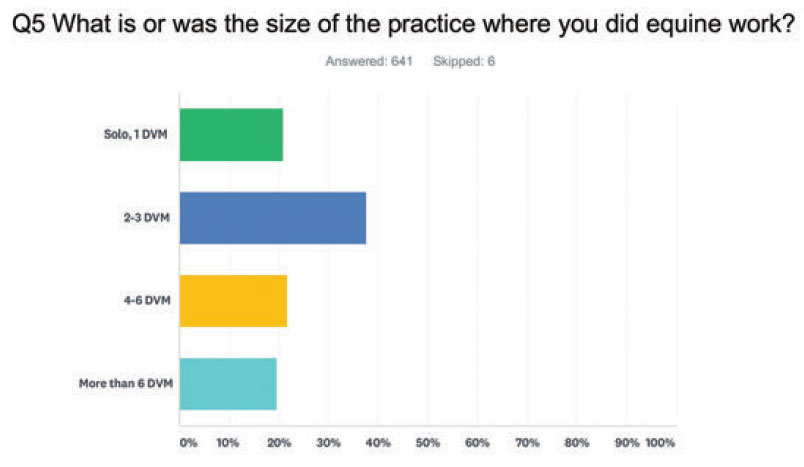

Respondents were fairly equally distributed among different sized practices, providing a view of equine veterinarians across a variety of work settings. While 20.9% reported being solo practitioners— well below the approximately 40% of AAEP members that report being solo—a majority reported working in practices of two to six veterinarians. Another approximately 20% reported working at large practices with more than six doctors. When those respondents who had never considered leaving equine practice were not included, practice size responses were virtually the same, leading one to conclude that practice size might have little effect on veterinarians leaving equine practice (see Figure 5).

Would You Leave?

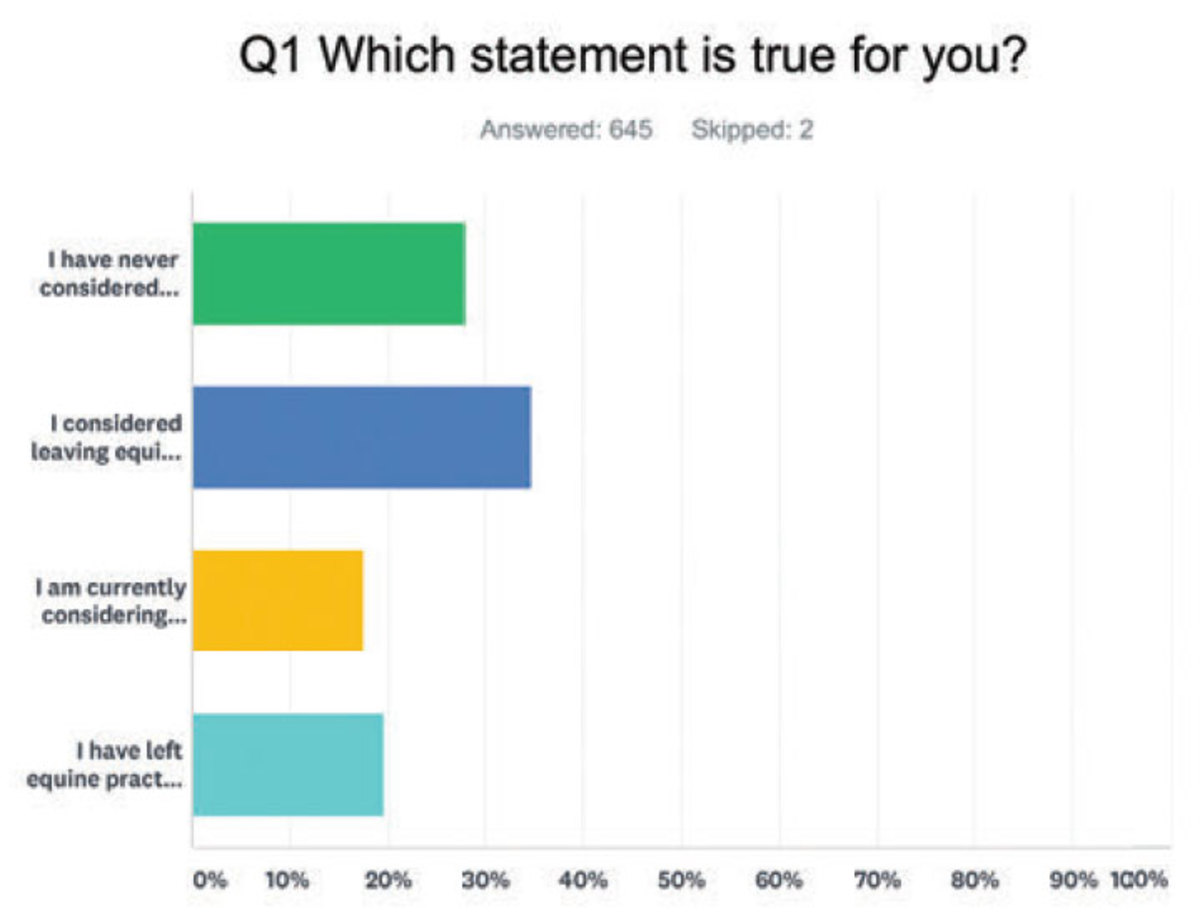

The most important questions in the survey were those that focused on leaving the profession. The first question in the survey asked, “Which statement is true for you?” and the answers included:

• “I have never considered leaving equine practice”;

• “I considered leaving equine practice but decided to stay”;

• “I am currently considering leaving equine practice but have not decided,” and

• “I have left equine practice or have definitely decided to leave equine practice.”

Somewhat shockingly, only 181 (28%) of the 645 respondents have never considered leaving the profession, of which 107 graduated in 2009 or before. Of the 80 respondents who graduated in 2016-2018, 22 (27.5%) had never considered leaving and 30 (37.5%) had considered leaving and decided to stay.

Similarly, 20.6% of the 126 respondent graduates of 2013-2015 had never considered leaving, and 35.7% had considered leaving and decided to stay. Of those 110 respondents graduating in 2010-2012, only 22.7% had never considered leaving equine practice and 37.3% had considered leaving and decided to stay.

Because the recession of 2009-2011 affected equine practice substantially, one might have expected there to be higher attrition in those graduation years, but the data does not support this.

Sadly, 127 (19.7%) of the 645 respondents have left or have decided to leave equine practice, and another 113 (17.5%) are currently considering leaving the profession.

When considered by graduation year, 19.5% of those graduating in 2009 or prior have left or have decided to leave, compared to 18.2% of those who graduated in 2010-2012; 27.0% of those who graduated in 2013-2015; and 11.3% of those who graduated in 2016-2018.

Currently considering leaving the equine veterinary career path are 14.9% of 2009 or prior graduates, 21.8% of 2010-2012 graduates, 16.7% of 2013-2015 graduates, and 23.8% of 2016-2018 graduates. The data suggests that the reality of life as an equine practitioner might become untenable to some after several years in the career (see Figure 6).

Understanding why talented equine veterinarians are leaving the profession was the main objective of this survey, and to that end, questions were asked to identify both the contributing as well as the primary reasons for the exodus.

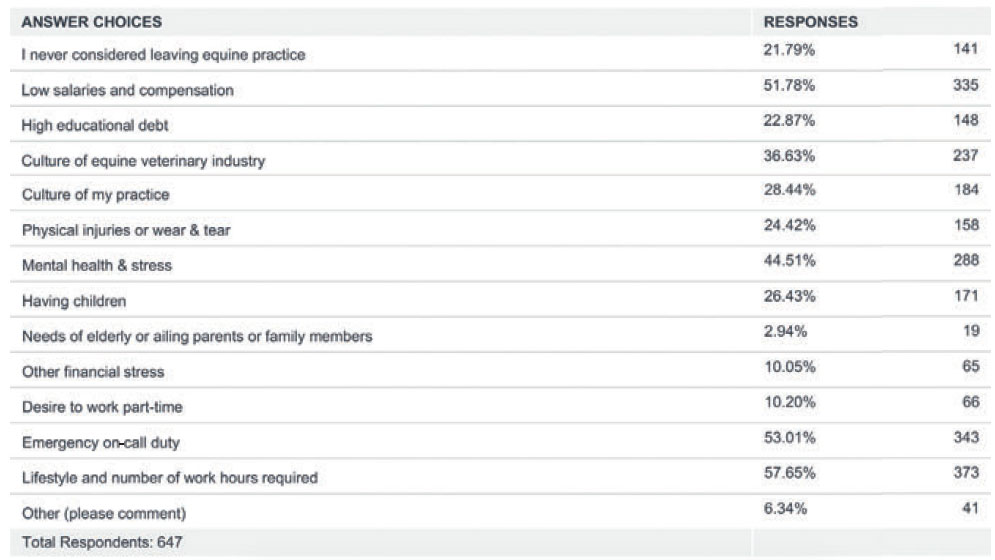

The top five contributing factors when respondents could select all factors that influenced their decisions were lifestyle and number of work hours required (57.7%), emergency on-call duty (53.0%), low salaries and compensation (51.8%), mental health and stress (44.5%), and culture of equine veterinary industry (36.6%).

Mentioned less frequently as contributors to leaving equine practice were culture of my practice (28.4%), having children (26.4%), physical injuries (24.4%), and high educational debt (22.8%). The least chosen factor was needs of elderly or ailing parents or family members (2.9%) (see Figure 7).

One respondent commented about her reasons for leaving the equine veterinary profession, saying, “I think for me, the main reason I could not make equine practice work was because of the culture and demanding hours. It was a challenge before kids, but afterwards it became impossible. Being on call 50% of the time with a newborn that didn’t sleep was an enormous strain on our family, and if I’m being completely honest, it put my marriage in jeopardy. Then taking time off to take my sick daughter to the doctor was a strain on the practice.

“Planning to leave early one day to pick up my kid on a day my husband had a late meeting was a lot to ask. Trying and failing to make it home in time for dinner was the norm. The list goes on. I did look for other equine jobs, but never found one in our area that seemed to be enough of an improvement to make it worth it.

“For now, I am doing small animal, and hope to get back to equine after my kids are a bit older—maybe solo. I hate to be another female vet that couldn’t make it in equine practice. It’s all I ever wanted to do since I was 7; I completed an internship and almost accepted a residency; I thought I was well prepared and fully informed on what to expect out of this career path. I love equine medicine, but could not find a way to do it and also feel like I was being a good mother/wife—or even daughter/sister/ friend, etc.”

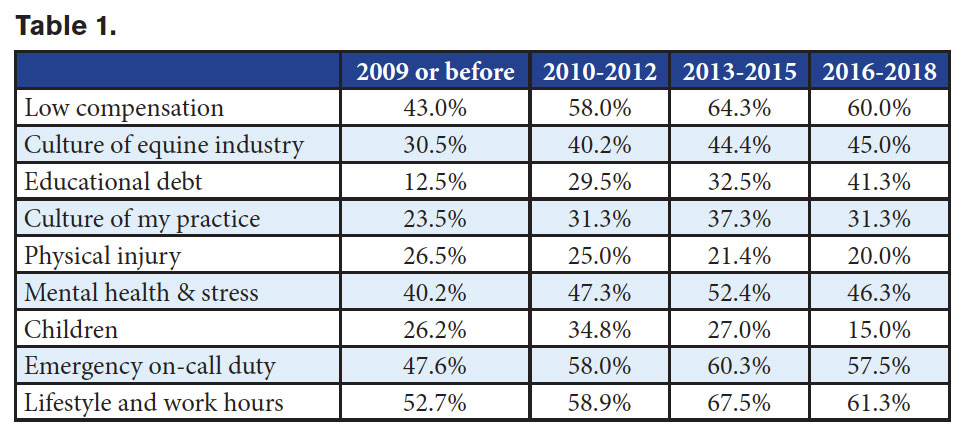

The most prevalent reasons chosen for leaving equine practice did not differ considerably between graduate year cohorts, but there were interesting trends in the percentage of respondents choosing each option.

Lifestyle and number of work hours required was the most frequently named contributor to respondents’ decisions to leave or consider leaving equine practice across all graduation years, cited by 52.7% of those graduating in 2009 or before, 58.9% of those graduating in 2010- 2012, 67.5% of 2013-2015 graduates, and 61.3% of respondents from 2016-2018.

Those from more recent graduating years were more likely to attribute low salaries and compensation to influencing their departure, with 43.0% from 2009 and before, 58.0% from 2010-2013, 64.3% from 2013-2015, and 60.0% from 2016-2018 citing this factor.

One respondent commented, “I could literally not afford to eat meat … I love the job, but it wasn’t sustainable.”

Emergency on-call duty and mental health/stress were less frequently reported by those graduating in 2009 or prior compared to the most recent decade’s graduates. A rising trend in the importance of educational debt and the culture of the equine veterinary industry was seen across graduation years (see Table 1).

Why Leave?

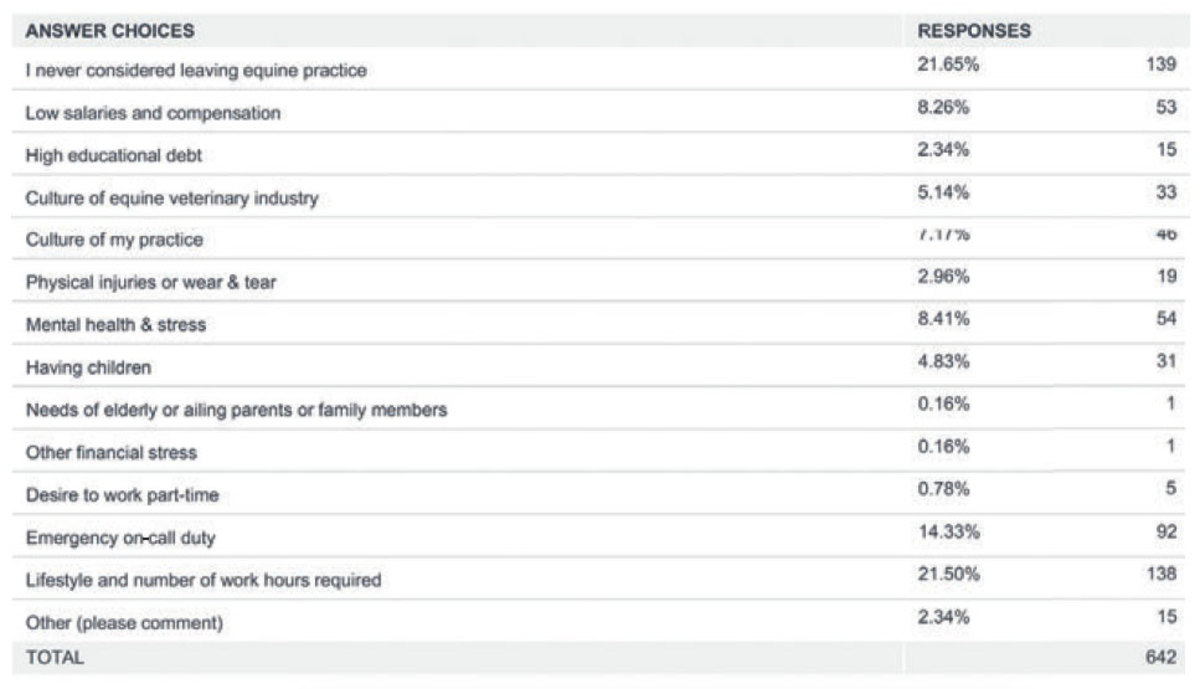

Respondents to the survey were asked to choose the most important factor in their decisions to leave equine practice. Not surprisingly, the factors that were the most prevalent when multiple rea sons could be chosen again rose to the top.

Across all graduation years, lifestyle and number of work hours required was the most frequently chosen response (27.5%), followed by emergency on-call duty (17.9%) and mental health and stress (11.6%). Low salaries and compensation (10.0%) garnered fourth place in importance, followed by culture of my practice (9.8%) (see Figure 8).

Respondents showed a love for the profession but a frustration with the constraints of the culture. Said one, “Equine practice is still very much a lifestyle, not a job. The line between clients and friends is blurred. Not only must you be available 24/7 and are made to feel guilty if not, but forget about going to the barn to play with your horses uninterrupted. I go only when I know others won’t be there, and it causes me more anxiety than calm.

“As much as these clients act like friends, I am a monkey that serves them. And if I died, they’d find another monkey. That’s a tough reality when you dedicate your life to something. The people, the stupidly low pay and the constant on-call make it sick. The horses make it worth it.”

As another put it, “As I’m sure many people will say, the on-call and the hours (working every weekend during breeding season whether on call or not, staying late frequently, etc.) are major contributors in considering leaving equine practice. When most of my friends were vets this seemed normal, but now that many of my friends have non-vet jobs I am insanely jealous of their ability to make definitive evening and weekend plans, have entire weekends off, and not be restricted to the on-call radius and tethered to the phone. I enjoy emergencies but have come to hate being on call.”

Interestingly, only 6.3% selected the response of having children as the primary reason for leaving or considering leaving the profession. This might reflect the fact that because having a family is a natural and expected part of most adults’ lives, those aspects of practice that do not allow for this normal life phase would be called out as the reason, not the act of having children. Comments certainly highlighted the difficulties of veterinarians blending young families with equine practice as it exists today.

Said one doctor, “I never considered leaving until my daughter. I was all-in, gung-ho equine. And then she came along and the time, financial and quality of life sacrifices I was making for the privilege of working with horses were not just my sacrifices anymore. I was also in a fairly family friendly practice, but it’s still the reality of equine practice, especially at the referral level, because ‘the buck stops here.’ I miss horses, but I love my family more.”

Said another, “I’m one of the ‘dark side’ converts … I was a solid equine ambulatory vet for 11 years, then worked a handful of small animal days while on maternity leave with my second kid. Ended up making the switch. It has been good for me and my family, but I still struggle with my choice some days.

“The decision was primarily made to have better quality of life with two kids. I now work only four days a week, with no on-call, and I earn considerably more. I struggle with the decision, partly from the sense that I ‘gave up’ my passion/ dream career, as well as proving that a mom can be a badass equine vet (which I did, working through two pregnancies, pumping, breastfeeding, carting a kid around on calls, etc.), but I had to also accept that doing what was best for myself and my family ended up being more important than my job.”

What Are You Doing Now?

The final question of the survey asked what those who had left practice were doing now. About 47% of respondents reported that they are now in companion animal practice, and another 10% have an academic position of some kind. Industry and government positions have each been taken by another 4% of respondents. Although opportunities in other areas of the veterinary field abound, those who have trained for and dreamed of a career in equine veterinary medicine often have sadness about their transition.

Dr. J.J. Vautier-Brown planned to be an equine surgeon and was proud to be chosen for an internship at Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital several years ago. She described her training there as exceptional and perfect for her career trajectory. After a second surgical internship at the University of Georgia, she was poised to apply for a surgical residency when she became pregnant.

Understanding that an infant wouldn’t mix with residency training, Vautier-Brown took a job at a mixed animal practice, where she was thriving. Unfortunately, a death in the family led to the need for a cross-country move to California, where finding an equine job within commuting distance was difficult. To pay her student loans, she took a temporary job at Banfield, where “they were really good to me, even though I only had equine experience.” She is still looking for an equine job. As she said, “I can’t do this small animal thing forever! It’s a job, not a career.”

Her second child is almost 2 years old, and her first is 4. “It is horribly crushing to invest eight years of your life to be a surgeon, loving every minute of two intense internships, but feeling like your dream has been crushed. But my son is the biggest blessing of my life, and I wouldn’t ever trade him for a residency.”

Vautier-Brown worries that her educational loans are a burden to her family and said, “I don’t know how to balance my love for my family, my career aspirations and my financial obligations. We don’t leave the equine profession because we want to; we leave because we have no other choice!”

Another Rood and Riddle alumnus, who intended to specialize as a theriogenologist, said, “Being a horse doctor was always my dream since I was 7 years old.” After her internship, which she described as an amazing experience, she began equine practice at a six-doctor firm. Although the practice seemed progressive in its medicine, the culture was not family friendly. Neither the staff nor other associates had children, and there was little teamwork.

“Every doctor was a silo, never sharing cases or treatments or helping each other.”

When this veterinarian became pregnant, she felt she needed to prove that she could do the work without accommodations because of the culture. She worked until the day she delivered, including emergencies. As her first child grew, she felt torn by the demands of her job, saying, “I felt I had to choose between the two and couldn’t have both. I felt like I wasn’t doing a good job in either role.”

When she became pregnant with her second child, she and her husband decided to move closer to family. Due to a lack of part-time equine employment opportunities in her new location, she took a full-time job at a companion animal practice working 36 hours a week with no emergency on-call hours. Her compensation is 50% more than her previous equine position for two-thirds as many hours. She stated, “I feel guilty, embarrassed and like I don’t belong in the equine vet tribe anymore. I took a spot at a prestigious practice for my internship, and now I’m not using that training. I used to judge people for leaving because they couldn’t hack it. And now that’s me.”

Take-Home Message

These stories of the career paths of some of “the cream of the crop” highlight the fact that even the “the best in class” are affected by our industry’s long-standing workplace traditions and outdated cultural mores.

In 2018, the AVMA reported that there were 3,142 U.S. veterinary school graduates and that 42 (1.8%) took an equine job at graduation. Another 146 entered equine internships. More than 50% of AAEP members are over the age of 50, and many are approaching retirement. Recent numbers of jobs on the AAEP Career Center have well exceeded 200.

Our profession cannot continue to stay strong with the loss of talent that we are now experiencing. New paradigms must evolve that allow our changing workforce to have the flexibility and support that they need while still keeping practices financially healthy.