Some areas of the country, particularly east of the Mississippi River, are endemic for botulism. Equine practitioners in those areas are familiar with clinical signs and protective measures. Other parts of the United States rarely see cases of botulism.

With changing climatic conditions and poor hay yields in many regions this year, forage might be imported from one area to another, bringing with it the risk of contaminated feed leading to outbreaks of botulism.

A recent botulism outbreak in Florida has highlighted this disease as a concern among horse owners and veterinarians. Joe Lyman, DVM, MS, director of Professional Services and Product Development for Neogen Vet, presented a webinar discussing details that are important to horse owners and veterinarians throughout the United States.

As a neurologic disease, botulism is rapidly progressive and 90% fatal, especially if left untreated. Early on it is difficult to differentiate it from other neurologic diseases or even colic. Clinical signs are caused by toxins generated from Clostridium botulinum anaerobic bacteria, one of the most potent toxins on Earth. Lyman reported that one pint is able to kill all human life; just 1 gram (1/2 teaspoon) can kill 10,000 horses!

Types of Botulism

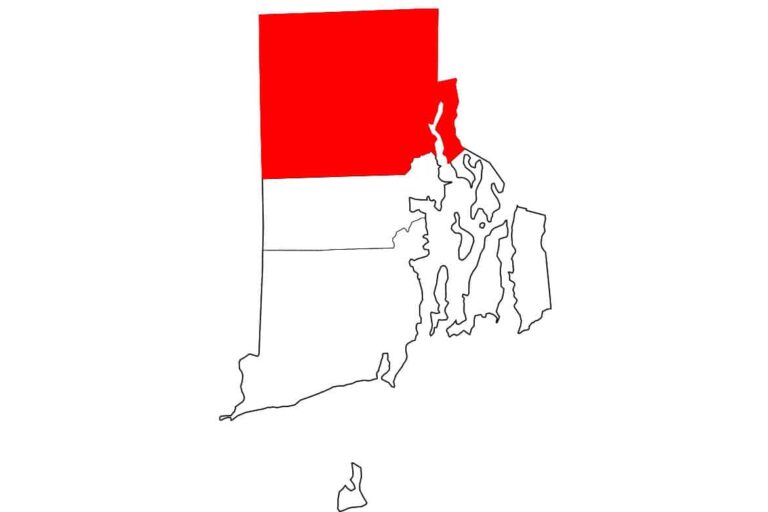

While there are eight different types of botulism toxin, Type B is responsible for at least 80% of equine cases and is most prevalent east of the Mississippi River. The western United States might also see cases of Type A that thrives in drier alkaline soil with little organic matter. Botulism can develop with three different forms:

- Forage poisoning is acquired by ingesting preformed toxin existing in a feed source from decaying grass, hay, grain, haylage, grass clippings or a decaying carcass. This is the most common form.

- Toxicoinfectious botulism (shaker foal syndrome) occurs when foals ingest spores from the environment—especially through licking dirt—rather than from ingesting hay. Then conditions in the foal’s gastro-intestinal tract favor bacterial growth and release of toxin that is absorbed systemically. By several months of age, these GI conditions diminish. Most cases of Shaker Foal Syndrome (70%) occur between two to five weeks of age.

- Wound botulism develops from soil contamination, especially of deep wounds with poor blood flow. These could be puncture wounds, injection site abscess and castration sites or umbilical infections.

Clinical Signs

The botulism toxin acts at the neuromuscular junction end plate by interrupting transmission of acetylcholine across the channels, leading to flaccid paralysis. Severity of disease depends on the dose of bacterial toxin involved.

Early on, the adult horse or foal displays decreased tongue, eyelid and tail tone. Clinical signs are symmetrical in severity and distribution, unlike asymmetrical signs seen with other neurologic diseases such as EPM.

With progression, botulism causes generalized weakness with non-specific signs such as a stilted or short-striding gait. Dysphagia is particularly symptomatic of botulism before other signs appear. Despite having a good appetite and wanting to eat, the horse is unable to coordinate muscle movements—feed drools from the mouth. While this might look like choke, feed and saliva dribble from the mouth and not the nostrils. A “grain test” (feeding grain by hand) is helpful to diagnose the difference.

Also, a botulism-affected horse is unable to control the rate of descent to the ground when trying to lie down, so he “plops” to the ground. Eventually, progressive paralysis keeps the horse recumbent; death usually occurs within 48-72 hours due to respiratory paralysis.

Shaker foal syndrome has similar signs, including muscle trembling or fasciculations. The foal is unable to nurse or swallow and might experience aspiration pneumonia.

Because botulism is not a central nervous system disease and only affects peripheral motor nerves, horses are completely aware of sensations of hunger, thirst, pain, fear or a full bladder. They are unable to move in response to their needs.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Often, diagnosis is presumptive based on clinical signs and history, as well as by ruling out other neurologic diseases. Most typical diagnostic tests such as PCR or antibody measurement take time, and these horses fail so quickly that it is impractical to wait for results. The faster the disease progresses, the worse the prognosis.

Treatment relies on aggressive strategies:

- Remove the likely source of toxin. Every minute contributes to paralysis that cannot be counteracted.

- Nasogastric intubation with mineral oil hastens GI transit time.

- Administration of antitoxin with hyperimmune plasma-trivalent antitoxin is best to address both Type A and B. Antitoxin binds to circulating toxin in blood but is unable to reverse damage to endplates. It takes seven to 10 days to regrow end plate tissue and without treatment, horses don’t have that much time before they die.

- Medical treatment includes antibiotics and intravenous fluids because of risk of aspiration pneumonia.

- Oxygen therapy is necessary in about half of cases, and 30% of horses might need ventilatory support.

Clinical signs can progress for another 12-24 hours following antitoxin administration. If the horse is not improving, another dose of antitoxin might be necessary. With timely intervention with antitoxin, 90% of horses recover. If horses are still standing at time of treatment, survival rate usually is high, but if the horse

is already recumbent, then survival rate is around 18%. In general, 62% of cases experience complications.

Prevention

Prevention is everything with botulism. It is a “silent killer” that can be fatal without warning. Ensure a good feed source, particularly when feeding round bales. Store hay off the ground and in a dry area. Control rodents and discard decaying feed.

Keep in mind that forage travels across the country. That means veterinarians and horse owners need to be acutely aware of the potential for botulism during drought periods when local hay sources are scarce.

Vaccinate horses living in endemic areas with BotVax B toxoid, a risk-based vaccine that is USDA-approved for use in horses. Lyman recommended vaccinating any horse fed high-risk feed—compressed feed, round bales, on-ground feeding—or those living in high-risk conditions. He also advised vaccinating broodmares within 45 days of foaling to maximize colostral antibodies. Other horses to consider vaccinating include equine athletes and horses with sentimental value. Botulism vaccine is boosted annually following the initial primary series of three doses administered monthly.