It’s an ongoing challenge for any professional, especially the ambulatory equine vet: managing your time and workload so that not only are you practicing good medicine, but in such a way that you’re not burning yourself out. Sometimes, this is a matter of mere logistics. In other cases, it requires a deeper evaluation of the type of medicine that you’re truly passionate about. It also requires thinking about how you can shape your practice’s focus to keep that passion alive. At any rate, avoiding burnout should be one of the equine veterinarian’s top priorities. If you don’t take care of yourself, how can you realistically expect to do the best possible job for your patients?

Robert Magnus, DVM, MBA, emphasizes that the best way to avoid burnout is to improve the practice’s internal operations. “Equine practitioners are very passionate about the horses, but oftentimes, we don’t apply that same amount of energy into setting up our businesses properly,” says Magnus, the founder of Wisconsin Equine Clinic & Hospital and Equine Business Management Strategies in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. “We’re really good at going out and doing emergency calls. But when we’re exhausted from being out there and working so hard, we don’t have good processes and people back at the practice to take care of the operational things that happen throughout the day.”

Taking Care of Business

This invariably adds another level of stress to the job. For example, if you dedicate your busy season only to attending to calls, what happens when things slow down and you discover that your accounts receivable are far behind what they should be? All of a sudden, it’s time to pay bills but you are unable to due to lack of cash flow. “When you look at the things that will help a practitioner reduce burnout, it’s the human resource management and the internal control management of the practice,” Magnus says. “Most of us work so hard, but we don’t take care of our shop at home.”

Bryan Buescher, DC, recognizes that one of the biggest challenges that equine vets face is the 24/7 nature of the business. “In some situations, they feel like they get boxed into that,” observes Buescher, a coach with The Ideal Practice in Temecula, California. “They feel like they’re the only doctor in the area that can see these animals, and therefore they have to be that go-to person regardless of the time of day.” As a result, equine veterinary businesses are based upon a reactionary model, rather than a proactive structure.

For Roland A. Thayer, VMD, of Metamora Equine in Metamora, Michigan, burnout is the result of boredom. Thayer is a solo practitioner who works with a full-time veterinary technician on the road with his wife, Bonnie, managing the office. He underlines the importance of goal-setting, accompanied by a plan that enables practitioners to see the progress they are making. “I find that if I set a goal and work towards it, seeing that goal start to evolve and develop is exciting and it keeps me focused and on track,” he explains. This could mean setting into motion a project that contributes to the streamlining of the business, such as synchronizing the practice’s imaging archive system to ensure that all of the images are properly stored, recorded, managed and are easily accessible. “That’s a goal, and seeing it develop is somewhat exciting and keeps things interesting.”

Schedule Carefully

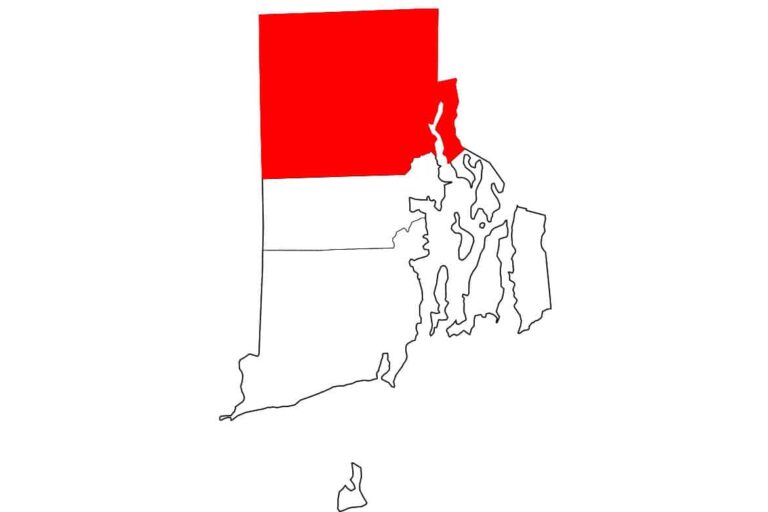

Aimee M. Eggleston, DVM, established Eggleston Equine in Woodstock, Connecticut–in which she is the sole fully ambulatory veterinarian, with her husband managing business affairs and a receptionist running the office. One of her biggest goals was to structure scheduling in such a way that allowed for enough face-time with patients and clients, while taking into account the amount of time she would actually be spending on the road.

“When I worked for other practices, one of the frustrations was how the schedule was done. Specifically, how much time was allotted for appointments, and the expectations related to how long those appointments would take and the travel time in between,” she says.

As simple as it may sound, travel time makes up a significant portion of any vet’s day. So does the time it takes to examine patients and relay the resulting information to horse owners. “When I branched off into my own practice, I knew that having an unreasonable expectation as to the number of appointments per day would contribute to burnout.” By paying attention to scheduling, Eggleston doesn’t feel rushed when dealing with clients. And, clients are satisfied that their questions are being answered.

Scheduling management involves a bit of trial and error. It also requires a clear understanding of how much you need to earn balanced with how much work you are realistically capable of performing, and performing well. While it’s a difficult thing to do, Eggleston emphasizes that sometimes, it’s better for the practice–and its patients–if you don’t accept every case that is presented to you.

“Sometimes you feel like you have to keep driving and keep building that practice in multiple ways. It comes back to the business plan. We find that you don’t need to take anyone and everyone on as clients,” she admitted. “At the beginning, you take whomever, wherever and whenever because you want to start your business and make it profitable as quickly as possible. It can be hard to let that go, and to say, ‘I don’t need to have every single person in this area as my client.’” In some situations, however, turning clients away–or referring them to another practitioner–may be the ideal decision.

Buescher notes that in most cases, an ambulatory equine vet boasts two types of clientele: small, single or two-horse facilities combined with large farms or ranches. The tendency, he says, is to treat both in the same way, which can be time-consuming, especially when it comes to the smaller barns. Buescher suggests that where possible, vets should encourage single or two-horse owners to bring their animals to the veterinarian’s own facility for examination in the interest of better time management.

“Some vets that I’ve worked with actually have trailers that they rent out to owners so that they can come in and do their own deliveries,” he offers. “Encourage people to bring their horses in to your facility, at specific times, on specific days, to get them into more of a routine. If they can schedule that routine ahead of time, it becomes much easier.”

Stick to Eight Hours

It’s also important to avoid becoming a slave to the sun. Eggleston recounts a piece of advice a veterinarian gave her back when she was externing: “We were driving around, and it was around daylight savings time, and he said, ‘You have to be careful – just because there are more hours of daylight available doesn’t mean you have to work until it gets dark,’” she recalled. “It’s so simple, but every single equine veterinarian has probably gone against that, or forgotten that.” If there are three additional hours of daylight, the temptation to continue working is high, but veterinarians are people, too, and they need to remember to take time out of their days for themselves.

This means managing your personal life as well as your professional one. Thaler relays that one of his interests is photography, and in his spare moments–sometimes even when he is out driving around, and has enough time in between appointments–he takes photos.

“I’m learning how to use a new lens on my camera, and I am developing some proficiency with photo-imaging software,” he explains. “It makes life interesting for me and that limits the burnout.”

He also notes that if one does start feeling burned out, she should examine whether part of this can be attributed to who she is in regular contact with.

“It’s important to determine whether or not you are surrounding yourself with people that are grinding you down. Overcoming burnout means managing negativity. You don’t want to speak negatively, and you don’t want to be around people that are making you negative; you want to be around uplifting people.”

As much as they may wish to, it’s important for vets to concede that they can’t be all things to all people (or horses). As your practice expands, it’s necessary to ask yourself: do I enjoy all aspects of the medicine that I am practicing? If you’re finding yourself attending to cases that you’re not that excited about, consider changing your focus.

Eggleston relays that a couple of years ago, she decided that the reproductive aspect of equine medicine no longer captivated her. “I don’t feel that I’m as current as some of my other colleagues and I don’t enjoy it,” she says, adding that lameness and pre-purchase work is what she prefers and concentrates on. “I made the blanket decision that I would not handle the breeding of these mares.”

She advises vets to remain attuned to what it is they really enjoy doing, because this can play a factor in the onset–or avoidance–of burnout. “If I concentrate the bulk of my time on what I enjoy doing, I will have an enjoyable day as opposed to having to deal with other fields that don’t excite or challenge me as much.”

Beat Back Boredom

Keeping things exciting may not even involve doing something as drastic as eliminating a practice area. “With veterinary medicine, it’s very easy to get burned out if you limit yourself to what you’ve been doing for the last 10 years and keep on plodding through the same-old, same-old,” Thaler said. “Once you start feeling bored, that’s a warning sign that you need to start learning something new.” This may simply mean acquiring more knowledge or gaining a new certification in your area of focus. “Feeling bored is your system’s way of saying, ‘Learn something.’ If you set a goal and start working towards it, you’re not going to get bored.”

One way of managing heavy workloads is sharing that work with other practitioners in the area. Eggleston notes that her focus on networking and developing relationships with the other equine practitioners in her area has given her the comfort of knowing that if it is difficult for her to make an appointment or an emergency call, most times, she will be covered.

“People say, ‘You’re a solo practitioner; you have to do all of your own emergency calls?’ Yes, it’s a challenge,” she admits. “However, I do have great relationships with the other vets so that my clients can call other vets if I’m not able to work. I can leave and get away.”

While the signs of burnout–lack of patience, a shorter temper, fatigue–are obvious, in many cases the sufferer is so wrapped up in taking care of business that they don’t notice it themselves, Magnus points out.

“Most likely, your significant other, your spouse, or your staff and friends will recognize these signs before you do, and usually you’re too busy to listen,” he says. “Listen to the people around you that care about you, because they are probably right. Take care of yourself; if you’re not in a good place in your life it will affect everything around you.”

SIDEBAR

A Helpful “Tech”-nicality

Roland A. Thaler, VMD, of Metamora Equine in Metamora, Michigan, has practiced ambulatory equine medicine completely alone, as well as with a veterinary technician. When he started his equine veterinary business with his wife, Bonnie, they decided that the investment in a full-time vet tech was well worth it.

“My most important time is my face-time with my clients,” he says. “I can’t have that face-time if I’m walking back and forth to the truck with equipment.” The transfer of trust and knowledge that takes place between doctor and client is one of the most important aspects of medicine, he says. Plus, many of the techniques and procedures that he currently performs require a second set of hands. “I really need someone there to operate machines or hand me things while I’m doing the procedure, so there is that part of it as well.”

Bryan Buescher, DC, a coach from The Ideal Practice in Temecula, California, believes that the cost of hiring a vet tech involves more of a return on investment than one might think, especially when it comes to time. “The doctors have time – that’s what they bill,” he says. “It’s very important for them to recognize that the more they can maximize their time, the more effective they’re going to be.” If you can pay someone $10 to $15 an hour to help support you to be more effective, it will add to your bottom line.