Whether you are interested in buying or selling shares in a group practice, buying an entire practice outright, merging with a colleague, or are considering transitioning out of practice ownership altogether, determining the fair value of the practice is the foundation of a successful transaction. There can be important tax considerations for both buyers and sellers with ownership transfers, as well as essential elements of partners’ operating agreements to consider. Consulting with accounting and legal professionals about these matters is recommended.

Editor’s note: The Fall 2020 issue of EquiManagement contained this article “Understanding Practice Value” written by Amy L. Grice, VMD, MBA. Portions of the article cited material written by Mr. David McCormick and the VetPartners Valuation Council publication “Valuation Essentials” and proper credit was not given in the magazine article. We apologize for leaving the citation off of the magazine article.

Types of Ownership Transition

Practice sales can be in entirety (100%) to a group or individual, or the practice can sell a percentage of the shares to bring in a partner. Sometimes neighboring practices decide to merge to increase economies of scale, share resources, and minimize on-call duties. Large hospital practices sometimes acquire small or solo practices in their regions to ensure referral streams.

Mergers require careful attention to details such as which practice’s software and price list will be used, whether the practice will have a new name, and how the shares of the new company will be allocated.

Generally, both practices are valued by the same professional, using identical assumptions to make appropriate adjustments to the financial statements. Then the shares in the new company are apportioned to the new owners accordingly.

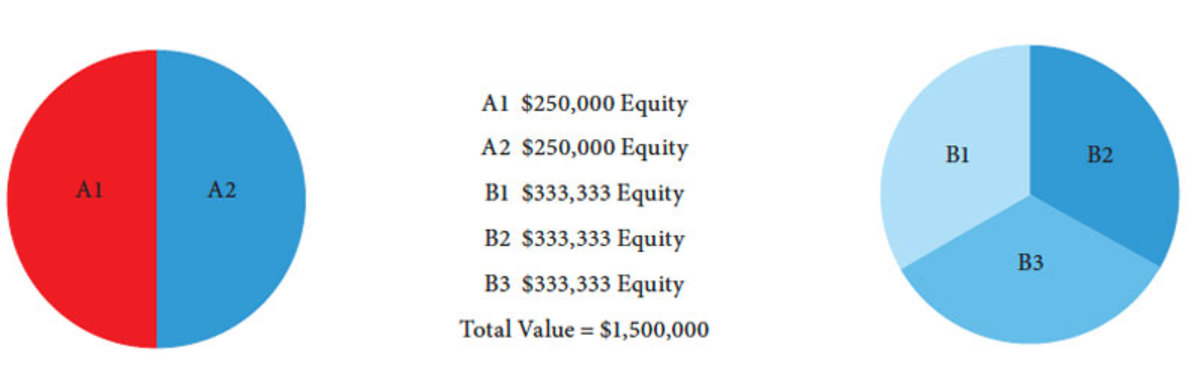

For instance, if Practice A with two equal owners is valued at $500,000 and Practice B with three equal owners is valued at $1,000,000, the merged practice value of $1,500,000 will be apportioned as follows: Owner A1 16.66%, Owner A2 16.66%, Owner B1 22.22%, Owner B2 22.22%, and Owner B3 22.22%.

If the new entity wished to have five equal partners, Owners B1, B2 and B3 would each sell 2.22% of their shares, with Owners A1 and A2 each purchasing 3.33%. (See diagram above.)

Acquisitions allow larger practices to increase their reach through satellite practices. This is a strategy often undertaken by hospital practices to ensure a good referral base. An ambitious practice of any size could also work to consolidate a group of nearby solo practices as their owners near retirement in order to insure practice growth. This orderly transfer often appeals to retiring veterinarians who are concerned about ongoing good care for their clients and patients.

Other acquisition patterns in the marketplace now include corporate buyouts such as those initiated by MAVANA, NVA and Avanti (see EquiManagement Summer 2020 issue).

Valuation

In performing a valuation, it is necessary to adjust the practice’s financial statements in order to determine the practice’s true profitability. this is because financial statements can vary widely depending on practice management and tax accounting policies. As a result, they rarely reflect true economic reality.

The goal of such adjustments is to restate the financial statements so that they reflect the fair market perspective of the revenues and expenses on an ongoing, operational basis.1

How owners are compensated is often the most important adjustment. The value of a practice primarily rests on the profit that the practice produces. Because profit drives practice value, it is necessary to separate owner(s)’ compensation for their effort as veterinarians from their compensation for taking on the work and risk of ownership.

When determining value, financial reports are corrected to reflect owners being paid for their efforts as veterinarians as though they were associates—in other words, by the same formula. This accounts for what the practice would be required to spend to replace the owner(s) if they were injured or otherwise unable to work in the practice.

However, because some practice owners might receive different benefits (e.g., family health insurance versus single, or expenses for a personal horse’s medical care) the compensation formula (% of revenue production) might vary between partners in order to provide equitable compensation.

If owners’ compensation for their work as veterinarians is not accounted for, excessive profit will be shown on the financial statements and will not accurately reflect the practice performance.

An owner’s share of profits is the return on that individual’s investment in the practice. If a partner owns 10% of the shares, typically he or she would be entitled to 10% of the profits. However, sometimes a particular partner (the “rockstar”) might produce vastly more revenue than another, which would provide more profit to the pool. Or one owner might be nearing retirement and only working part-time, while his or her partners work significantly more hours.

The partnership’s or corporation’s operating agreement will specify how profits are distributed—by ownership percentage or by revenue production percentage.

Buyers should thoroughly understand how compensation for shareholders is managed before making the purchase.

While owner compensation might not seem important for sole proprietors, when it comes time to sell shares to an associate or outside party, having clean financial reports that clearly show profit after appropriate compensation for the owner(s)’ professional work is important. This allows accurate profit—the basis of value—to be portrayed.

Compensation for management duties flows to owners according to the percentage of the tasks they undertake. Generally, 1-3% of practice gross revenue is set aside for management compensation. If one partner does 100% of the management, the entirety of this money would flow to him/her. Salary and bene- fits for a practice manager should also be allocated from these funds.

Therefore, a small practice with $1 million in gross revenue has a maximum of only $30,000 for management compensation. This is an indication that hiring a full-time practice manager would be premature. An allocation for management is another typical adjustment made by the valuator, if this is not already in place.

When a practice owns a facility, the real estate is generally held in a separate entity for liability protection. Owners of the real estate entity receive compensation for their return on investment in real estate. The real estate corporation pays the mortgage and leases the facility to the veterinary firm. Any net proceeds from lease payments are distributed to the real estate owners after all expenses are paid.

Real estate income is particularly sought after because Social Security and Medicare taxes are not collected on these monies, so often lease payments can be maximized to increase this tax savings.

Thus, another adjustment that is frequently made when determining value is to the amount of a lease. Typically, the annual lease should not exceed 10-11% of the appraised value of the property or 4-6% of the practice’s gross revenue production.

After this adjustment, there are three approaches to valuing businesses, with one used most frequently for evaluating veterinary practices. The three methods are the Market Approach, the Asset Approach and the Income Approach.

The Market Approach determines the value of a business by comparing it to similar businesses that have been sold in the open market. The comparable businesses must be substantially similar, but not necessarily identical, to the business being valued. The challenge, of course, is finding data about veterinary practices that are substantially similar and have sold recently.

Since most practices are privately owned, data about their sales is not generally public knowledge. Consequently, the Market Approach is seldom used in valuing veterinary practices.2

The Asset Approach derives the value of a practice based on the current value of each asset it owns. Beyond tangible assets (trucks, medical equipment, inventory, etc.), a very significant component of the value of a veterinary practice lies in the intangible asset often referred to as goodwill.

In considering the value of goodwill, a subjective decision must be made by the valuator, because there is an important difference between personal (professional) goodwill versus practice (enterprise) goodwill.

The practice goodwill value is determined by the net income that the practice generates. The value of the practice goodwill is not found in the practice attributes of reputation, client list or geographic area in which the practice operates. Though these things might contribute to profitability, practice goodwill is only quantifiable as the profit that the practice generates.

On average, 70-80% of the practice value will be associated with practice goodwill. The practice goodwill value will be proportionate to the earnings of the practice after fair compensation for professional and managerial efforts.

Profitability of a practice not only affects the return on investment distributed to the owners over the years of operation, but also has a large effect on the sale price of the practice at retirement.

One of the risk factors when purchasing a practice is the seller’s ability to effectively transfer professional goodwill. How difficult that transfer is depends on whether the professional goodwill belongs to the individual owner, to the practice or to some combination of both.

In a one-doctor practice where the owner knows all the clients and treats all the patients, the reputation of the practice is highly related to the doctor. Therefore, if you were to buy that practice, it would be critical that the owner transfer his/her personal goodwill by introducing you to the clients, speaking highly of your qualities as a veterinarian and as a manager, and working to convince the clients that they will continue to be in good hands.3

By contrast, in a multi-owner and multi-doctor practice, where clients might routinely see various doctors based on available slots on the appointment calendar, they will likely be bonded more to the practice than to an individual doctor. Clients in this instance understand that all of the doctors practice quality medicine and are all representatives of the practice’s brand identity. If one doctor or owner leaves, the odds are good that clients will continue to utilize the practice’s services.

This is an example of practice goodwill, which is easier to transfer to a new owner and less risky for a prospective owner to purchase.4

However, sometimes one of the owners is a very high producer of revenue and has a star-quality reputation, making it likely that revenues will fall when that veterinarian leaves, unless he or she has transferred significant case load in the year or two before departure. When determining future revenues and profits, the “rockstar” factor must be considered by the valuator.

The tangible assets are priced at fair market value. Fair market value can roughly be considered the replacement cost of the subject asset multiplied by its remaining useful life. As an example, a 3-year-old ultrasound machine with a life expectancy of six years and replacement cost of $20,000 would have a value of $10,000 [(6-3)/6) X $20,000]. A professional appraiser is used to establish the value of tangible assets.

The Income Approach is the most common means of appraising a professional service business such as a veterinary practice.5 This method bases value solely on the ability of the practice to generate income (profit).

Fundamentally, this approach has the greatest appeal in that value is based on anticipated future returns. This approach pays no regard to the value of individual assets, because both the tangible and intangible assets are collectively responsible for generating the income upon which the value is based.

The Income Approach views the practice as an investment: The income the practice is forecasted to produce is the return the practice owner receives for making the investment.

There are three types of Income Approaches: Capitalization of Earnings/ Cash Flow Method, Discounted Earnings/Cash Flow Method and the Excess Earnings Method.

Logically, the greater the return, the more valuable the practice is. Unfortunately, many practices provide owners with a good job and a comfortable living, but they generate little earnings (profit) beyond the owner’s salary. Inasmuch as these practices do not produce a fair and expected return on investment, they are of little value.

The value of a business is not based on what it owns as physical assets, but rather what it earns in profit using those assets. In other words, when you sell your practice, you will really be paid for the company’s ability to make money. If you have limited or no profit, all you have is used equipment to sell.

The Income Approach focuses on the income statement (P&L). It is founded on the theory that a business should yield a fair return on the owner’s capital invested in the business. For valuation purposes, both “earnings” and “fair return” need to be defined.

For tax reasons, business owners of “S” corporations often want to minimize their salaries in order to maximize their profit distributions, which pass through to them as individual investment income and are not subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes.

In other types of corporate entities, owners might want to maximize salaries in order to minimize taxable profits. In addition, owners usually want to credit the company with as many discretionary (personal) expenses as possible. Strategies such as these will help hold down the company’s taxable income; therefore, “earnings” must be restated to reflect the actual return on investment to the owner, in order to determine the accurate value.

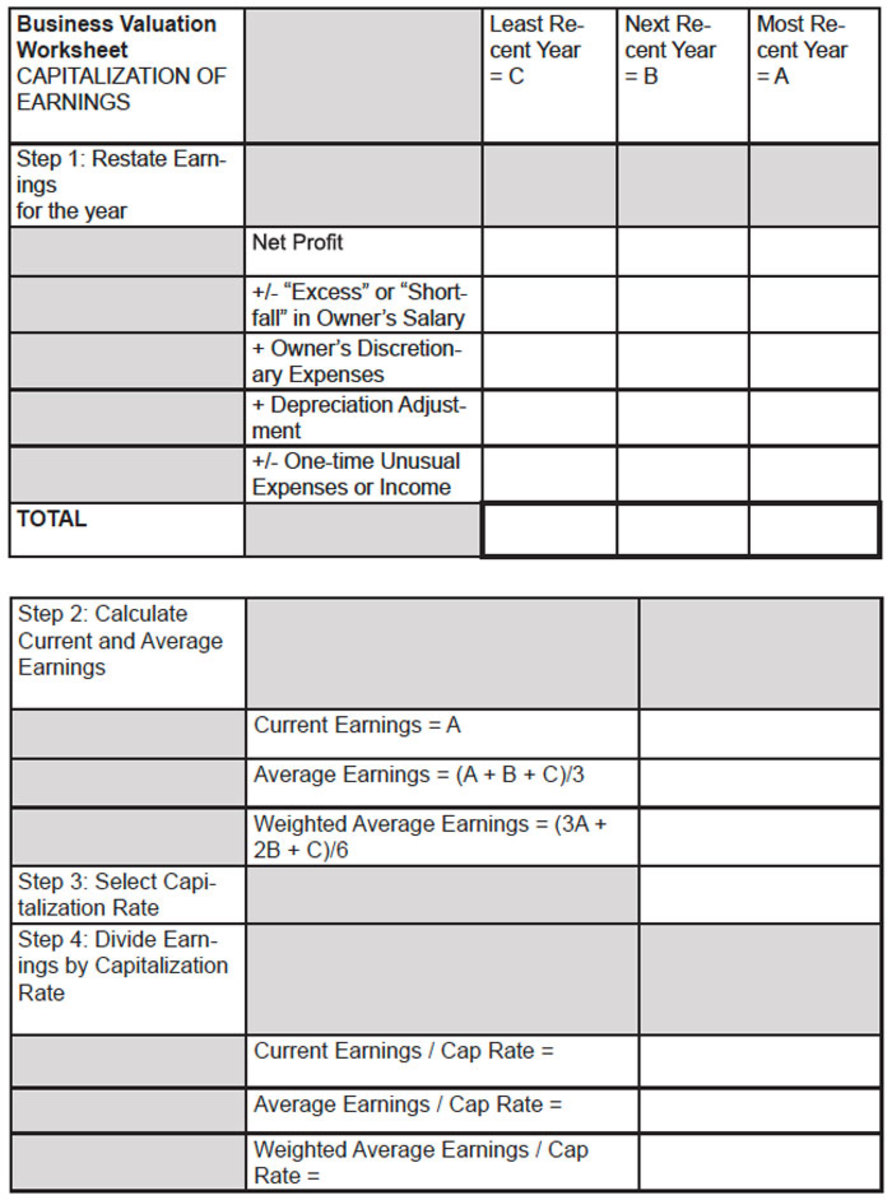

For closely held businesses, “earnings” are commonly defined as a combination of:

- the accounting net profit +/-

- excess or shortfall in owner’s salary— the amount an owner is paid above or below the amount a hired veterinarian would be paid for the same job +

- depreciation/amortization expense (non-cash expense items) +

- discretionary expense items (personal expenses) +/-

- extraordinary one-time expenses or income

The value of the company is based on what it will earn in the future, not on what it produced in the past. But the past provides the basic data on which to base future projections.

Past earnings can be used in three different forms to calculate value. The basis for selection would be which form most accurately reflects the earnings which the company is expected to produce in the future:

- average earnings (for three to five years)

- weighted average earnings (for three to five years)

- current (or most recent) earnings.

The earnings available to the owner of a business represent a return on the funds that have been invested in the business—in simplest terms, the initial capital stock plus retained earnings (cash that could have been distributed but was left in the company).

As an example, if a buyer were to invest $100,000 in a practice and wanted a 20% return on his/her investment, the business would need to produce $20,000 per year ($100,000 Å~ 20% = $20,000) in earnings (profit).

Taking the opposite approach, if a business produced $20,000 in earnings per year and a prospective buyer required a 20% return on investment, he or she would, in theory, be willing to invest $100,000 in the business.

Stated another way, the value of a business that produces $20,000 in earnings per year is worth $100,000 for a buyer that requires a 20% return on investment. In this example, the “20%” is the “capitalization rate,” and it is equivalent to the required return on investment on earnings. Capitalization rates can be used to determine the value of a business, based on earnings.

The higher the risk in an investment, the higher the required return will be. A buyer would require a higher rate of return on investment from a business that was perceived to be higher in risk. The capitalization rates for “risky” businesses are, therefore, higher than those for less risky companies.

The commonly used capitalization rates for veterinary practices are 20-40%. The capitalization rate is the inverse of a multiple of earnings: A “cap rate” of 20% equals a “multiple” of 5.

Using the previous example: Earnings $ 20,000 x multiple of 5 = value $ 100,000.

If this practice were at higher risk, the capitalization rate could be 40%, or a multiple of 2.5. In this case, the practice would be worth $20,000 x multiple 2.5 = value $50,000.

In other words, the key for value is how much profit and how much risk.

Determining the appropriate capitalization rate for a given practice is one of the most significant responsibilities of the valuation professional since small variations in the capitalization rate can change the determined practice value significantly.

Risk factors that a buyer should consider in purchasing a practice include consistency of past revenue growth, expected future earnings, transferability of goodwill, location, quality of staff and facility, demand for services, regional demographics, effective practice management, competitive environment, practice stability and lease terms.

A capitalization rate multiple of 5 generally reflects a well-managed practice with multiple doctors, all of whom “ride for the brand” and will continue producing the same amount of revenue after the sale.

This profitable practice would also have excellent risk mitigation by having written policies and procedures, compliance with OSHA, DOL and DEA regulations, and dedicated, long-term staff members. Minimizing risk increases the capitalization rate multiple.

(Note: You can calculate your practice’s valuation using the diagram below.)

The Discounted Cash Flow Model is similar to the earnings method described above. This method has become one of the standards in valuing equine practices over the last decade. In essence, your practice is worth exactly the amount of excess money it can generate for the new owner or shareholder into infinity, discounted to today’s present value.

This can be calculated via a formula and is then further discounted (35-65%) for transferability (ease in sale compared to publicly traded stock). When a practice is valued fairly, buyers should be able to service the debt, interest and tax (on the flow of cash that they receive for being an owner) with their share of the profit (cash flow) when the sale is financed over 10 years at the prevailing interest rate. To get a quick semi-accurate estimate of your practice’s value, you can use a calculator at www.calcxml.com/calculators/business-valuation.

Purchasing an existing practice is generally a safer investment than establishing a new practice. This is because the existing practice has an established clientele and a history of financial performance and resulting cash flows (profit).

However, a fair valuation of the practice being purchased is of paramount importance to the purchaser. Regardless of the valuation approach or methodologies used to derive a value, the purchaser must develop projected financial statements to ensure that there is sufficient cash flow to meet the financial obligations of the practice after purchase.

When fairly valued, a practice should have sufficient cash flow to allow the new owner to retire the debt obligation associated with the purchase over 10 years after being fairly compensated as a veterinarian and business manager.

Through the initial decade of practice or share ownership, regardless of whether it is a startup or a purchased practice, significant equity will accumulate, but little money will likely be available to be extracted for personal use unless the practice and profit are growing. However, after the debt associated with the practice purchase is satisfied, ownership allows the practice owner to reap higher income than that a veterinarian could earn as an associate because of distribution of profit.

In addition, at retirement, the equity that has accumulated can be harvested when the owner sells the practice or his/ her shares in the practice.

Take-Home Message

Practice ownership is the key to financial success in equine practice, but a fair valuation is essential for the transaction to occur.

Sellers need to allow three to five years of ownership before sale of their practice or shares in order to utilize efficiencies to increase profit and value, and potentially to correct business practices that obscure true profit. Add Worksheet

Resources

1 David McCormick, MS CVA Simmons & Associates State College, PA, USA

2 Vet Partners Valuation Council “Valuation Essentials for Veterinarians” https://1fhivcvvu5m2qa2i427xyuc1-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Val-Essntl-for-Vets-2017-version-10.pdf

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #18391](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wp-s3-equimanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/30141438/EDCC-Unbranded-5-scaled-1-768x512.jpeg)