Recently, a robust discussion began on the Parenting Rounds of the AAEP listserv. A pregnant veterinarian asked for advice on preparing for the change in her life that was soon to occur.

Her questions ranged from what to expect her energy level to be, to whether it was realistic to think she could take the baby with her in the truck (she was a solo practitioner). Many caring colleagues shared their own experiences and helped answer her questions.

To gather more information about this topic, a 12-question survey about parenting was posted on both the Parenting and New Practitioners listserv groups of the AAEP. A total of 135 veterinarians responded, 29% of them male and 71% female.

The goal of the survey was to gather information about the experience of becoming a parent while employed in the career of equine veterinary medicine. The questions explored the demographics of the families, how child care was provided and what accommodations were made by the practice. Then we compared the expectations before delivery to the reality after the baby arrived. It was clear that the respondents wanted to be heard on this topic, as the majority took the opportunity to write comments about their experiences.

Who Responded

Respondents were asked about the number of children they have. A strong majority of respondents reported having just one (37%) or two (47%) children. Three children were reported by 13% and four by just 2%. The children are mostly under 6 years of age, with 35% reporting one child in that age range, and 26% reporting two. However, 32% of respondents reported that all their children were over the age of 6 years.

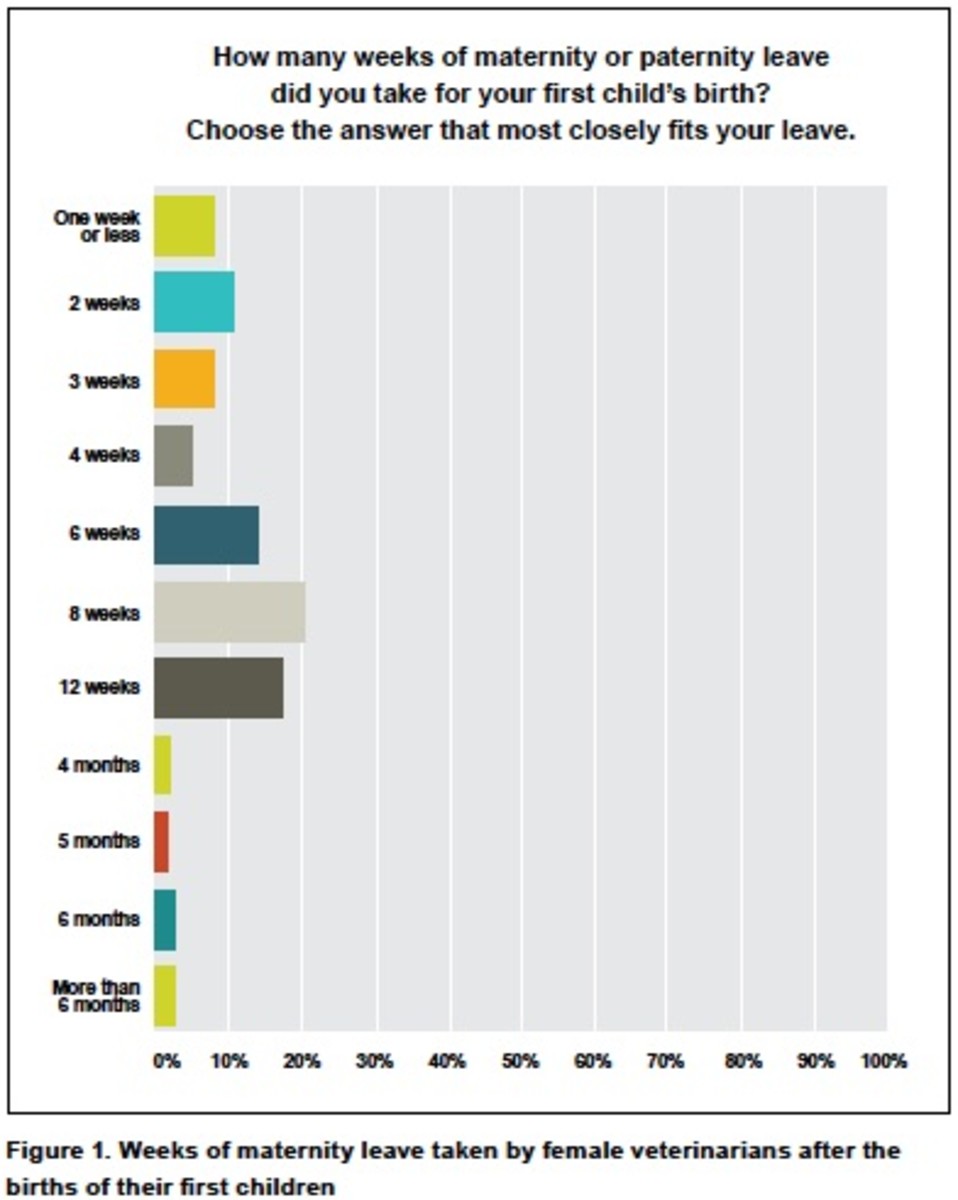

Responses to the question “How many weeks of maternity or paternity leave did you take for your first child’s birth?” were filtered by gender. Male respondents overwhelmingly (89%) took one week or less of leave after the birth. Females had a much broader range of time taken, undoubtedly driven by their personal circumstances. Sadly, 9% of new mothers took one week or less of maternity leave, 11% took just two weeks, 9% three weeks and 5% four weeks. This data indicates that 34% of post-partum women took one month or less to recover from birth and bond with their infants. Six weeks of leave were taken by 15% of female respondents, eight weeks by 21% and 12 weeks by 18%. Much smaller numbers took extended leaves.

Even those women who reported leave times of an extended length sometimes were working prior to that leave ending. For example, one respondent commented, “Technically I took four weeks, but I was doing some appointments and did some reproductive work a week after she was born.” Another veterinarian who reported a week or less of leave commented, “No maternity leave was available with my associate position.”

The leave that was taken by veterinarians responding to this survey was primarily unpaid: 62% of females and 40% of males received no maternity/paternity leave compensation for the time away. Respondents’ comments indicated that they typically relied on a patchwork of vacation time, personal days, disability insurance and personal savings to meet their financial obligations while they were away from work.

One exception was a Canadian respondent who noted that in that socially advanced country, one year of paid leave is provided to share between both parents, with the stipend based on a percentage of previous earnings.

Maternity leave from employment after childbirth provides a critical time for maternal-infant bonding, physical healing from birth and adjustment to life with a new baby. A longer length of maternity leave is associated with increased breastfeeding duration, as well as improved maternal mental health and child development.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) passed in 1996 entitles eligible employees of covered employers to take unpaid, job-protected leave for specified family and medical reasons for up to 12 weeks. However, the FMLA only applies in the private sector to employers with 50 or more employees in 20 or more work weeks in the current or preceding calendar year. Very few veterinary practices are this large, but many of them follow this policy voluntarily.

In the general U.S. workforce, many women cannot afford to take unpaid leaves and instead use a combination of short-term disability, sick leave, vacation and personal days in order to have some portion of their maternity leaves paid. The U.S. is one of only five developed countries in the world that does not mandate paid maternity leave.

According to a report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2011, 65.9% of women in 2006–2008 reported being employed during their last pregnancy. Of those women, 70.6% reported taking maternity leaves. Thus, nearly one-third of employed women did not report taking any maternity leave (29.4%). When taken, the average length of maternity leave was 10.3 weeks.

Nationally, the proportion of women who took maternity leaves for their last children varied by race and ethnicity. Hispanic women were less likely to report having taken any maternity leave than non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic black women (59.5% versus 73.0% and 68.7%, respectively). Among women who reported taking maternity leave for their last pregnancy, 33.1% did not have any portion of their maternity leaves paid. Only 24.9% percent of women reported paid maternity leave for more than two months (nine or more weeks).

These figures represent the United States population of new mothers, not the cohort of equine veterinarians surveyed. The survey data suggested that the situation is certainly no better in the equine veterinary industry, and might be worse.

Did You Return to Work?

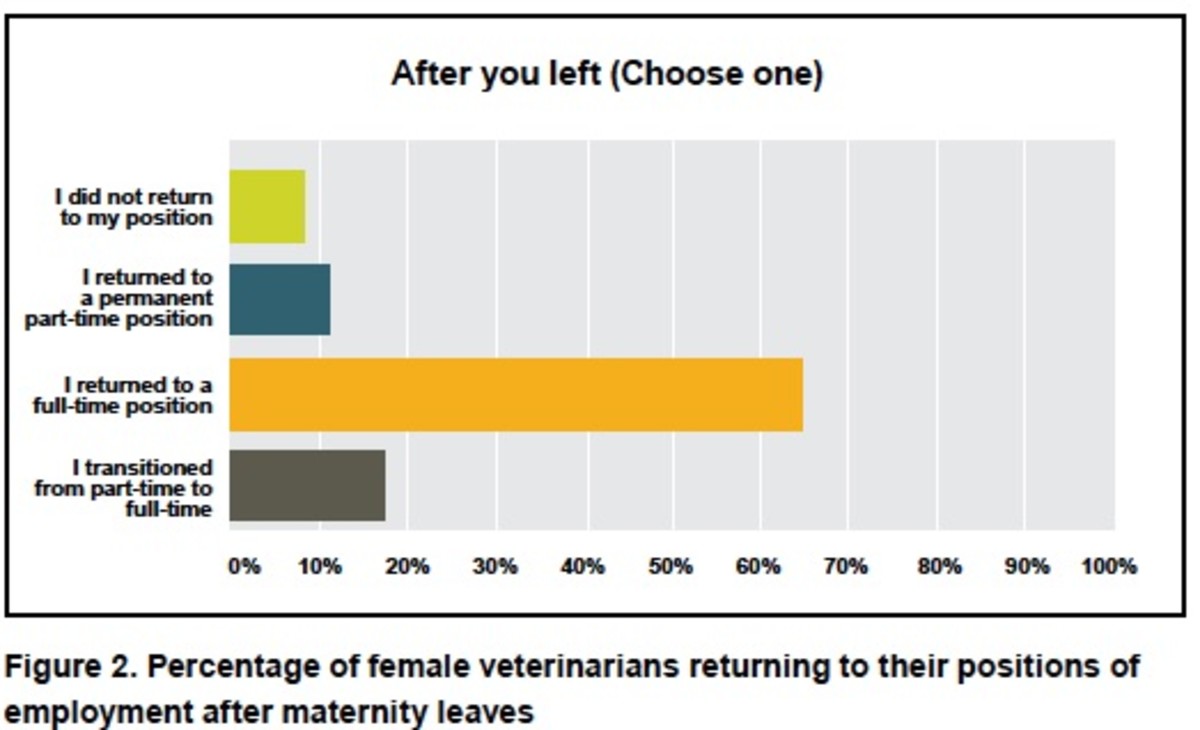

One concern expressed by older practice owners when discussing the marked demographic shift in equine practitioners’ gender over the last decade is that new mothers don’t always return to work at the end of their maternity leaves. When respondents were asked whether they returned to their employment positions after their leaves, 97% of males returned to their work full time. Of the females, 65% returned to a full-time position, 17% transitioned from part time back to full time over a period of time, 11% transitioned to permanent part-time work, and 7% did not return to their position.

Comments by respondents revealed that those in solo practice were generally able to adjust their schedules initially to have a lighter workload. Two female respondents employed as associates stated they were not allowed to return to work after their maternity leaves and were terminated. One subsequently filed a pregnancy discrimination suit against her former employer, while the other opened her own solo practice.

Child Care Options

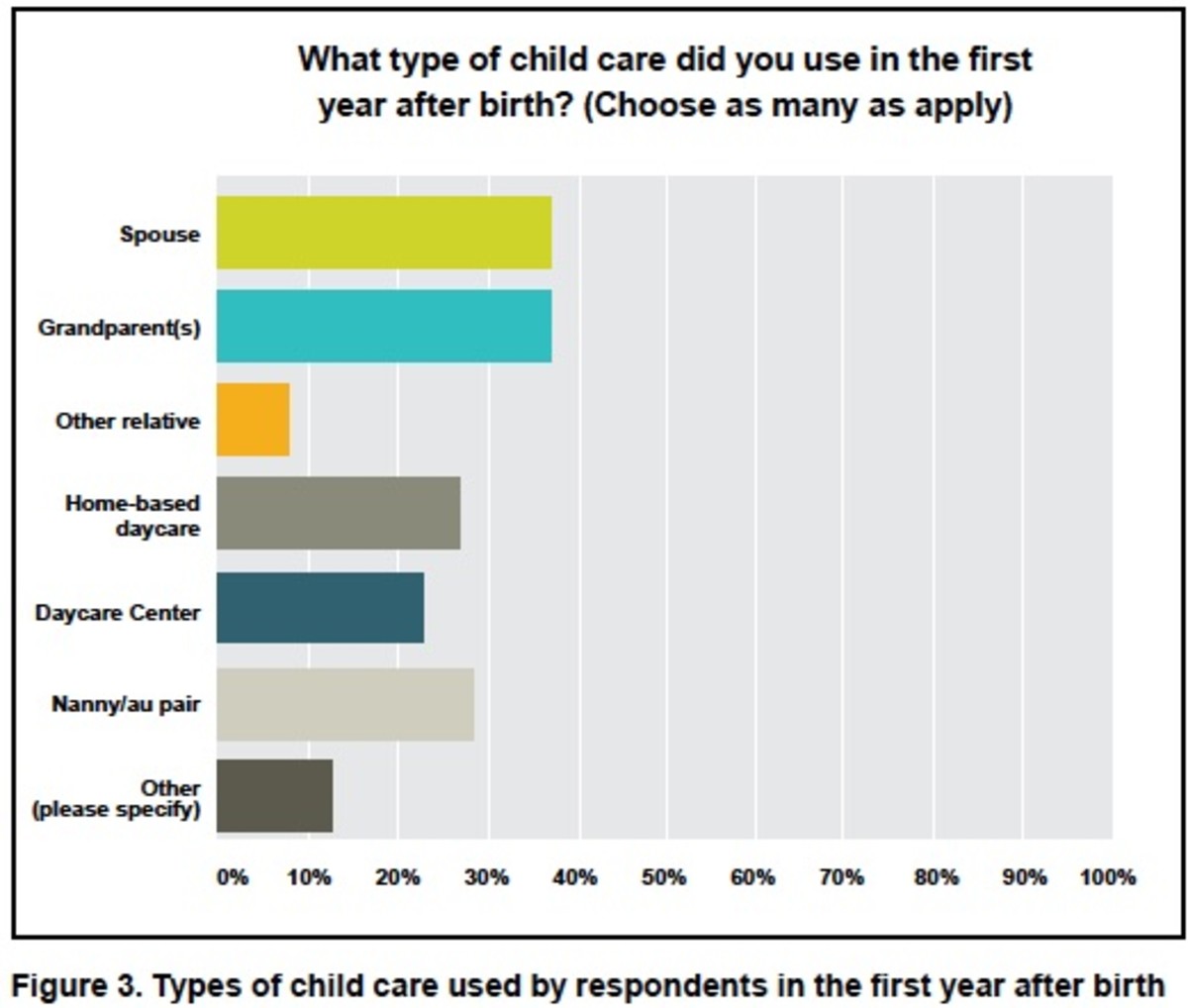

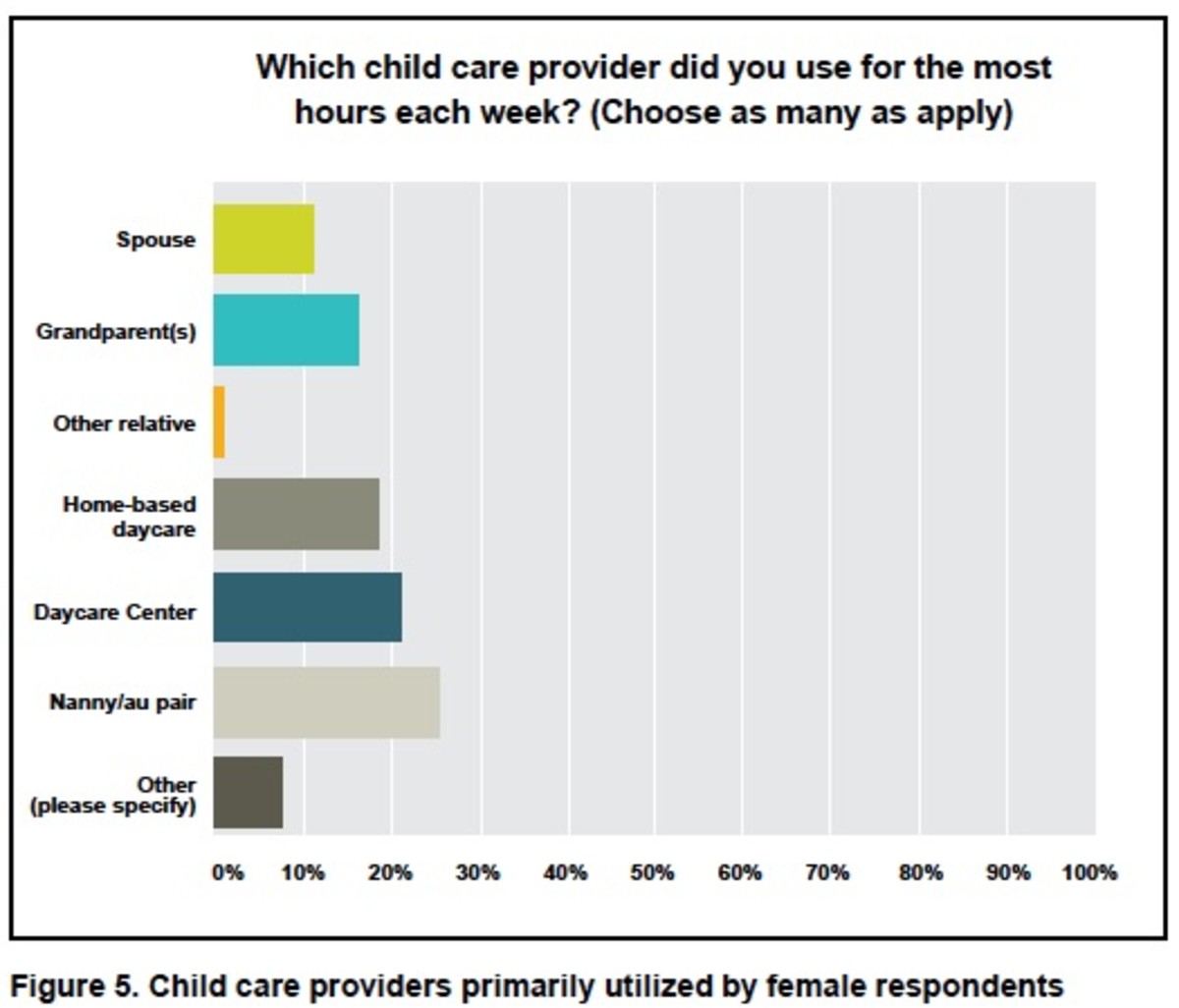

Equine veterinarians responding to this survey were asked to indicate all the different types of child care they utilized in the first year after the births of their children. Spouses and grandparents were both utilized by 37% of respondents, with smaller percentages also utilizing a nanny (28%), home-based daycare (26%) or a daycare center (22%). In addition, 7.5% used other relatives for care.

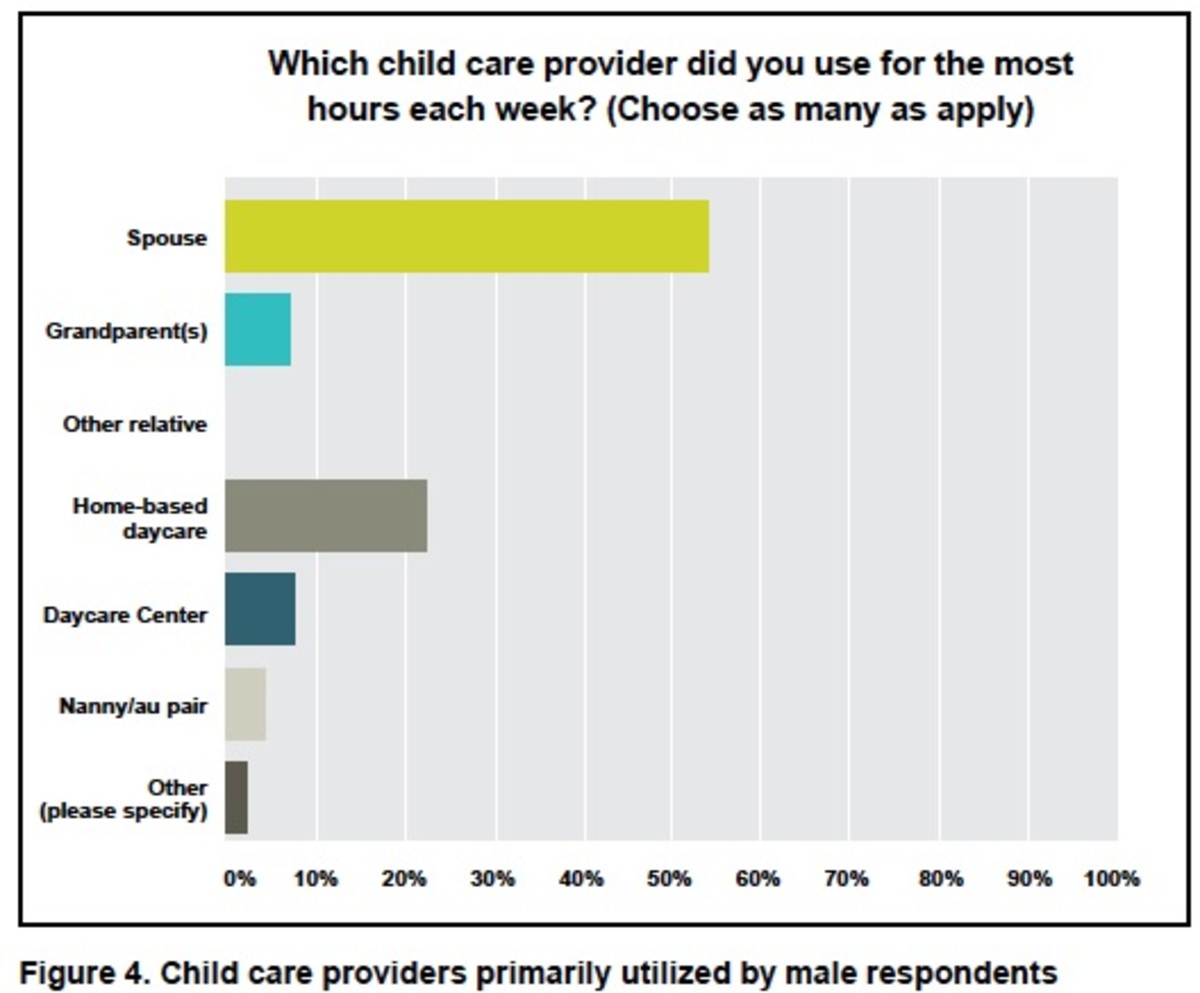

When queried which provider of child care assumed responsibility for the most hours of care, responses differed between male and female respondents. 54% of male veterinarians indicated that their spouses provided the majority of care, with 23% using home-based daycare primarily. Among the females, only 11% relied on a spouse to provide the majority of care. A nanny or au pair was primarily utilized by 25.5% of respondents; 20% depended on a daycare center; 19% used mostly home-based daycare; and 16% mostly had care from grandparents.

These statistics show that female equine veterinarians most often do not have the comfort of having their babies cared for by a family member, unlike the males. The stress that these women feel about parenting is most likely increased by this lack of relatives involved in child care. Meanwhile, gender roles in society continue to be weighted toward mothers caring for their children.

In a 2012 Pew Research survey, the vast majority of Americans (79%) rejected the notion that women should return to their traditional role in society. However, when asked what is best for young children, 42% said that having a mother who works part time is ideal and 33% said it’s best to have a mother who doesn’t work at all. Even among full-time working moms, only about one in five (22%) said that having a full-time working mother is ideal for young children. Thus, female veterinarians who are mothers might also face societal pressure and judgment about their choices to have careers.

Additional findings of the Pew Research Center suggested that women continue to bear a heavier burden when it comes to balancing work and family, despite progress in recent decades to bring about gender equality in the workplace. A 2013 Pew Research Center survey found that mothers with children under age 18 were about three times as likely as fathers to say that being a working parent made it harder for them to advance in their job or career (51% vs. 16%). In addition, they found that mothers were much more likely than fathers to report experiencing significant career interruptions in order to attend to their families’ needs. Part of this is due to the fact that gender roles are lagging behind labor force trends.

While women represent nearly half of the U.S. workforce, on average, they still devote more time than men to housework and child care, and fewer hours to paid work—although the gap has narrowed over time. When these responsibilities are layered on the robust working schedule of most equine veterinarians, the stage is set for some to become overwhelmed and unable to achieve balanced, healthy lives.

Parenting Concerns

Before the arrival of their first children, 52% of all respondents to the AAEP listserv parenting survey worried a great deal about not “being there” for their children. 32% worried about their schedule their time effectively, being physically or mentally exhausted, or having difficulty arranging child care.

Perhaps because of the close bond of infant to mother, females had more concern than males about emergency duty: 83% of females reported moderate to a great deal of worry versus 29% of males. Similarly, 68% of the women had concerns about physical and mental stress, versus only 31% of the men.

Of the female respondents, 47% worried about being seen as less dedicated by the practice owner, compared to 2.5% of the men. 48% of women worried about being seen as less dedicated by clients, compared to 13% of men. The survey showed that 64% of women worried about losing momentum in their careers, compared to 15% of men.

When these same factors were examined under the spotlight of reality after the birth of that first child, 77% of parents responding indicated that having enough time with their babies was a real concern. That result was not much different between the men (79%) and women (76%). Perhaps because so many of them had spouses providing the bulk of the child care, only 33% of male respondents reported experiencing significant physical or mental stress, compared to 72% of the female respondents.

“Overwhelming is an understatement!” commented one mother.

Career Fears and Facts

Although emergency duty did prove to be difficult for 67% of women and 23% of men who were new parents, the reality was less serious than they had imagined before the birth.

“On occasion, it seemed like coordination of child care for emergencies was a total disaster, but for the most part, it worked well,” said one female veterinarian.

“In the first six months, this was a huge issue, especially when trying to navigate breastfeeding and pumping,” said another.

Despite the challenges, these new parents found ways to meet their personal and professional responsibilities.

Losing momentum in their career trajectory was an issue for 45% of the females, but a concern for only 8% of the males. This result was more positive than the respondents had feared. However, one female respondent commented, “This is my number-one large fear, and I feel it is happening, which is a great source of depression for me.”

Another said, “I wish this were less true. I don’t regret my priorities shifting away from work and toward my girls, but I wish I didn’t get ‘punished’ quite so much for doing so.”

The same difference in perception held true for worries about being seen as less dedicated by owners and clients. men reported that difficulty in reality.

However, there were certainly some individuals who had different experiences. As one respondent commented, “Funny, I did not even think this would be a problem before I had my first child. Boy, was I mistaken!”

But another said, “The clients were very excited and supportive throughout my pregnancy, and often were glad to see me back and hear about the kids. I do not ever bring my kids along to farm calls, though, as I do worry this would make me seem less professional.”

Only 53% of females struggled with scheduling, which they had anticipated would be more problematic prior to the birth (69%). Interestingly, 33% of males reported concern with scheduling after their children arrived, but only 26% had been worried before birth. A stronger- than-expected bond of the men to their infants might account for those findings.

These statistics are strong evidence that the reality of having a child while working as an equine veterinarian is quite different for males than it is for females.

Practice Reality

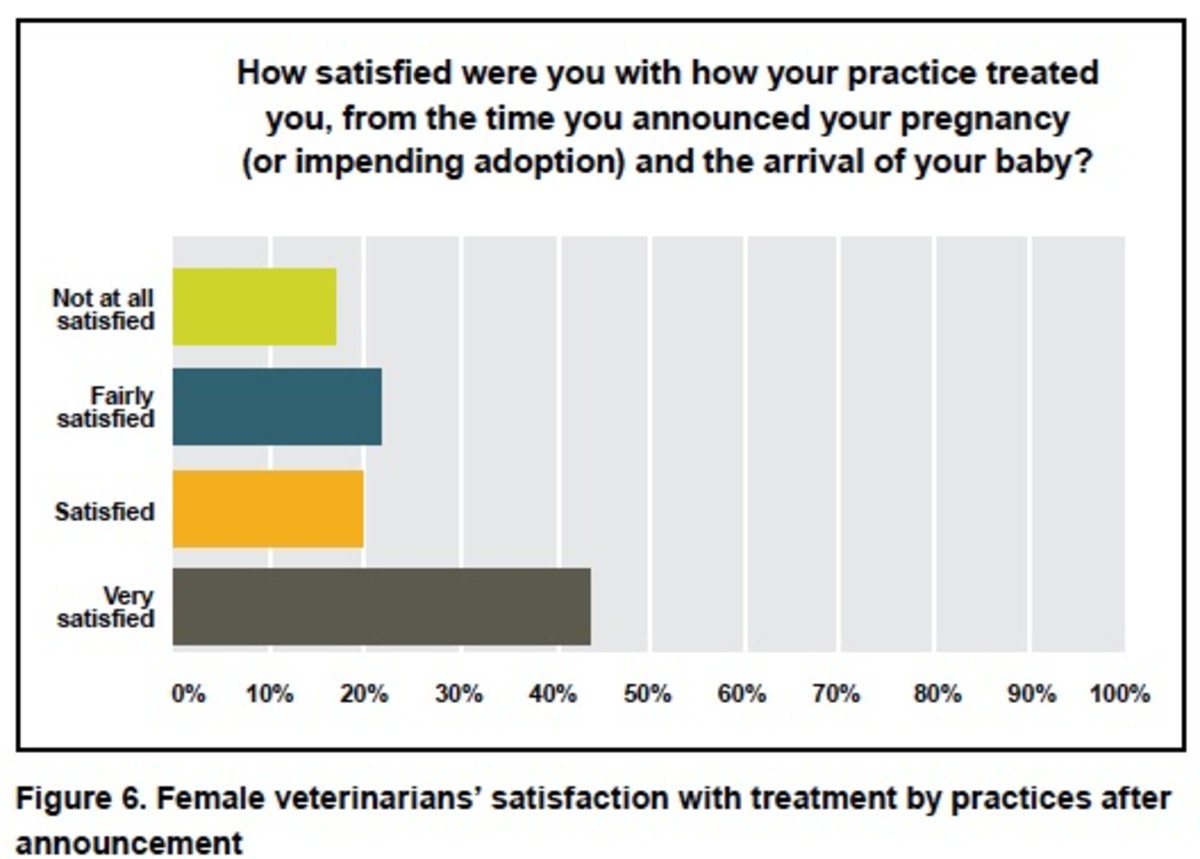

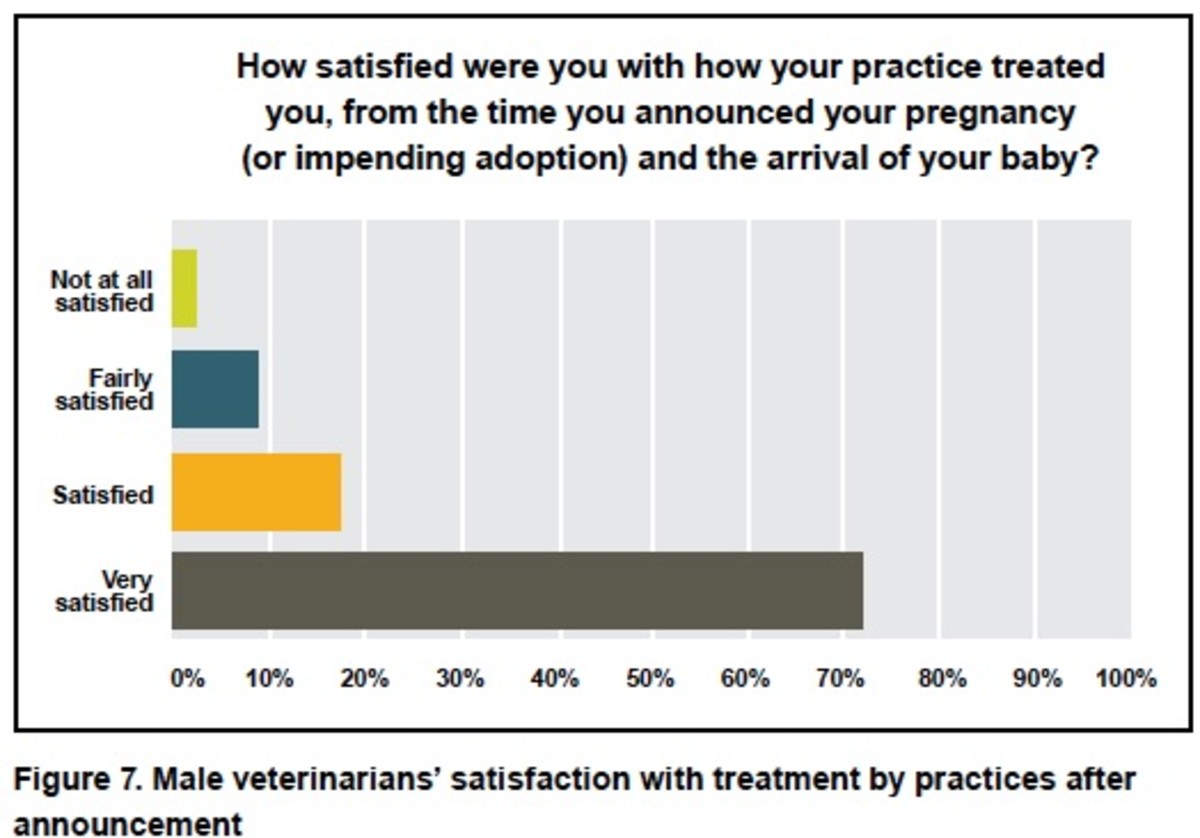

In the concluding question, the survey participants were asked how satisfied they were about how their practices treated them from the time they announced their pregnancies or impending adoptions until the arrival of their babies. Not unexpectedly, a very strong majority of the male respondents were satisfied, with 90% reporting they were satisfied or very satisfied. 43% of female respondents reported being very satisfied. One commented that she was “overwhelmed with how great everyone was and continues to be.”

Another veterinarian reported, “My practice was happy to hear the news, worked with me on my schedule, and picked up more emergency duties so that I wouldn’t have to be on call after month 7.”

Another 41% were satisfied or fairly satisfied. One new mother said, “It all turned out really well, but my practice does not communicate well. It was on my shoulders to be proactive and discuss any changes in my schedule, etc. They ended up allowing me to change my schedule completely as I had proposed it. After three months back with decreased hours, my production has increased every month compared to last year. I am much more focused and driven with my time at work and away from my child, especially while paying for child care. Having a child was one of the best things I have ever done.”

Unfortunately, the 16% of women who were unsatisfied had some pretty bad experiences. One veterinarian said, “I was told to hide my pregnancy, and then I was told, two weeks after a C-section, on the day my daughter was discharged from NICU, that I would be fired if I was not back to work in one week. We had previously agreed on six weeks leave. I had gone into acute kidney failure and delivered via emergency C-section. When I called to say I was being admitted to the hospital, I was screamed at and berated.”

Another female veterinarian said, “My employer was completely unsupportive during my pregnancy. I was appalled at some of their behavior.”

Take-Home Message

The current equine veterinary industry is largely made up of practices owned by older male veterinarians who employ younger female associates. Because of biological imperatives, the issues of pregnancy in practice, maternity leave and flexible scheduling in the early years of child rearing need to be addressed by practices in advance of the inevitable. It is clear from this survey that male equine veterinarians experience becoming a parent much differently than female practitioners.

Male practice owners need to look through the lens of the young women they employ and become familiar with their different perspective. Solutions to providing excellent patient and client care with a team of female veterinarians who have young families can lie in new paradigms. The old business model might need to give way to fresh approaches to equine practice.

Accepting the new demographic reality of the profession requires embracing change. Change is difficult, but practices leading the way into the future with new business models are likely to be the future success stories of our profession.