Equine veterinarians leave for companion-animal practice for many reasons, ranging from better work-life balance to compensation. One reason unique to the growing population of female practitioners is the struggle associated with getting pregnant and having a child on the job. “This is the issue we need to talk about,” says Christy Cullen, DVM. “We will continue to lose equine vets if we can’t support mothers.”

In a survey distributed in December 2024 on the Equine Vet-2-Vet and AAEP Member Facebook pages, 241 respondents shared information about their experiences with parenthood, most of whom had delivered their children within the past decade (see Figure 1). In this article, we’ll review their experiences to get a better understanding of how practices can improve policies surrounding pregnancy and maternity leave for equine vets.

A Look at the Stats

Most of the survey respondents only reported on their first birth, 21% reported on a second birth, and a few more on a third.

| Years | 1st Baby | 2nd Baby | 3rd Baby | TOTAL | % |

| 1990-2000 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3.3% |

| 2001-2010 | 29 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 11.0% |

| 2011-2015 | 46 | 5 | 2 | 53 | 17.6% |

| 2016-2020 | 65 | 25 | 3 | 93 | 30.9% |

| 2021-2024 | 91 | 18 | 3 | 112 | 37.2% |

| TOTAL | 241 | 52 | 8 | 301 | 100.0% |

Almost a third of the nearly 300 births reported were via cesarean section (see Figure 2). Of the first births, 77 of 238 were born by C-section, or about 1 in 3; that ratio remained consistent for second and third babies.

| C-Sections | 1st Baby | 2nd Baby | 3rd Baby | TOTAL | % |

| Yes | 77 | 17 | 2 | 96 | 32.2% |

| No | 161 | 35 | 6 | 202 | 67.8% |

| TOTAL | 238 | 52 | 8 | 298 | 100.0% |

Maternal complications were more common during first deliveries—with almost 30% of respondents reporting a complication—but were much less likely in second and third births (see Figure 3). Maternal complications during or after birth included eclampsia, gestational hypertension, postpartum hemorrhage, ileus, colitis, mastitis, incision site hematoma or infection, dystocia, significant perineal and/or pelvic floor damage, uterine prolapse with eversion, placental abruption resulting in disseminated intravascular coagulation, and postpartum depression. The need for maternity leave to allow ample time to recover after delivery should be easy to understand!

| Maternal Complications During or After the Birth | |||||||

| 1st Baby | % | 2nd Baby | % | 3rd Baby | TOTAL | % | |

| Yes | 71 | 29.7% | 6 | 11.5% | 1 | 78 | 26.1% |

| No | 168 | 70.3% | 46 | 88.5% | 7 | 221 | 73.9% |

| TOTAL | 239 | 100.0% | 52 | 100.0% | 8 | 299 | 100.0% |

Along with maternal medical issues, some babies also suffer birth-related complications. In this survey, more than 19% of first babies needed special care, along with about 13% of second and third babies. Many respondents referenced NICU stays related to prematurity, respiratory dysfunction, or other issues. In addition, some babies were treated for meconium aspiration, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, or physical injuries related to a traumatic birth. One baby was reported to have microcephaly. However, it is important to note that a vast majority of newborns are healthy (see Figure 4).

| Neonatal Complications or Need for Special Care | |||||||

| 1st Baby | % | 2nd Baby | % | 3rd Baby | TOTAL | % | |

| Yes | 46 | 19.2% | 7 | 13.5% | 1 | 54 | 18.0% |

| No | 194 | 80.8% | 45 | 86.5% | 7 | 246 | 82.0% |

| TOTAL | 240 | 100.0% | 52 | 100.0% | 8 | 300 | 100.0% |

Respondents’ Experiences Varied

It is impossible to predict what one’s birth experience will be like. “I was hospitalized at 31 weeks and delivered via C-section six days later,” reported one equine veterinarian who gave birth in 2022. “I was hospitalized for another week after delivery due to complications. My baby was in NICU for four weeks, and I was out of work for a total of ~19 weeks. I came back part-time for six weeks before going back full-time on a four days/week schedule. I had eight weeks paid through short-term disability. It definitely wasn’t the plan, but I’m so grateful that I was able to take the ‘extra’ time. My boss was very open to making whatever schedule I wanted/needed work so that I would stay in equine practice.”

Conversely, another practitioner reported, “When I told [my boss] I was pregnant, he looked right at me and said, ‘This isn’t something I thought I was going to have to deal with.’ ”

Carlin Jones, VMD, said when she underwent an emergency C-section in 2004 and her newborn daughter spent two weeks in the NICU, her boss threatened to fire her if she didn’t return to work. She worked up until the day her daughter was born and went back to work just three weeks later.

While her experience occurred more than two decades ago, these situations continue today. One doctor who wished to remain anonymous reported, “I had my first baby during residency in 2015 and had eight weeks paid. I returned to finish my residency without any penalty. I worked until my due date, then went over by a week before delivering. I had stopped doing rectals and tubing dangerous horses at about eight months because we had a great team in academia that could help keep me safe. My second baby was delivered in 2018 as an established associate in group practice—I was the solo internist. I organized a locum to fill in for while I was gone, and worked until my water began breaking as I was on call. I had a prolonged amniotic sac rupture and expressed concern about infection to my boss, who was also a mother, and she insisted that I was to stay on call over my due date and while I was laboring. I ended up having a traumatic emergency C-section. I took 10 weeks unpaid leave, then worked two weeks part-time, and was off call for 12 weeks. Although I stayed in equine, I left that practice.”

Many of the survey respondents said they felt unable to set boundaries and advocate for their own needs and those of their babies, perhaps because of the culture of traditional equine practice.

Timelines and Challenges of Returning to Work

According to a Harvard Business Review article titled, “4 Ways to Meaningfully Support New Mothers Returning to Work,” more than 25% of mothers return to work within two months of giving birth, and 10% return within four weeks or less, largely due to lack of access to paid federal leave in the U.S. Because equine practices are usually small, the industry lags behind in offering paid maternity leave for employees. The 2024 AVMA AAEP Report on the Economic State of the Equine Veterinary Profession indicated that just 14% of practices offered paid parental leave; this is an improvement over the 11% offering paid maternity leave cited in the 2022 AAEP Compensation Survey and the 7.6% offering paid maternity leave in the 2018 AVMA AAEP Equine Economic Report.

In this survey, 29.5% of the 288 responses indicated they received some amount of paid leave beyond accrued vacation or sick leave from their employer—an encouraging finding. Those working at practices with at least four doctors were more likely to have paid leave, with 37.3% reporting they received some paid leave.

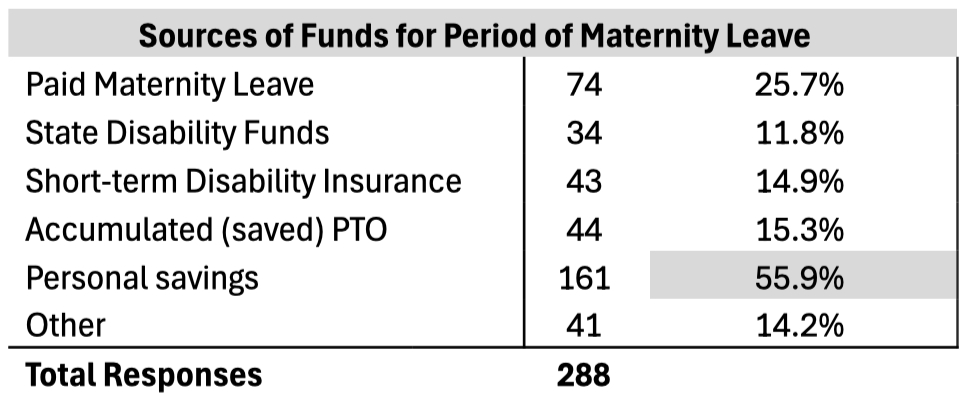

When asked to choose all the ways they funded their time away from work, most U.S. veterinarians used a combination of funding sources, with personal savings leading the way (see Figure 5). The few Canadian respondents touted their country’s one-year paid maternity leave policy.

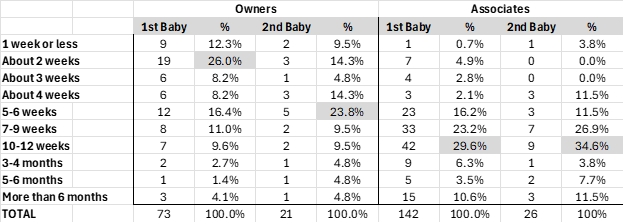

Among survey respondents, practice owners took much shorter leaves from work after birth than did associates. Solo respondents numbered only 10, so this phenomenon was not completely based on being the only veterinarian (see Figure 6). However, the responsibility to be present for clients, as well as financial stresses, might affect owners more than associates, especially for those in solo practices. As one solo owner wrote, “I still answered the phone. I took no appointments for two weeks with my firstborn but only took two days off with my second.”

Some solo practitioners have support systems that allow for different experiences. Solo practice owner Dr. Holly Bingman said, “For my first maternity leave, I took nine weeks, and for the second I took 12 weeks. I own my own practice, so I came back ‘part time,’ and then bumped up to my normal full-time schedule within three to four weeks. My mom watches my kids, so my schedule was very flexible with her. I have a huge support system with my family and some pretty wonderful supportive colleagues. I am a part of an emergency co-op sharing with three other women equine practitioners. We are all moms and without the on-call sharing, I could most definitely not do equine practice with my family. We support each other and lean on each other if we need to, so we can all have a quality of life and be there for our families. We rotate weekends and then cover each other during the week if needed and when going on vacation etc. I honestly think having people around you that are supportive of you as a mother and your journey has to be the norm for us to survive in equine medicine. It’s not easy, but it makes it all worth it if we can prioritize our families first. I am a strong believer we can have it all, but it may just be a little messy at times!”

More than 40% of equine veterinarians returned to work part-time after giving birth, at least for some period. Fifty-six percent resumed full-time work at the time of return, and 1.7% did not return to equine practice. Two respondents left veterinary practice altogether. One respondent who returned full-time said, “This was a mistake. I should have come back part-time to start. In retrospect, I was not ready either physically or mentally. But I needed a paycheck.”

Seventy percent of returning first-time mothers and 80% of second-time mothers started taking emergency shifts immediately when they returned to work. Among first-time parents, 12.3% started back on the on-call schedule after about a month, while only 4% of the second-time parents did. Twenty respondents said they stopped taking any emergency shifts. The comments in this section revealed the difficulty of after-hours duty for new parents.

“This was awful,” said one respondent. “In the first month back, during one stretch I didn’t see my baby awake for three full days due to my schedule and her sleep schedule.”

Another shared, “I could not have left a newborn to see emergencies. I would have fallen asleep at the wheel, not to downplay the unbelievable mental toll that would have taken, on top of being a new mother.” Difficulty with the unexpected nature of emergencies led one doctor to remark, “This was the hardest part to manage as it was impossible to know when you needed to leave, during the period when breastfeeding was really difficult.”

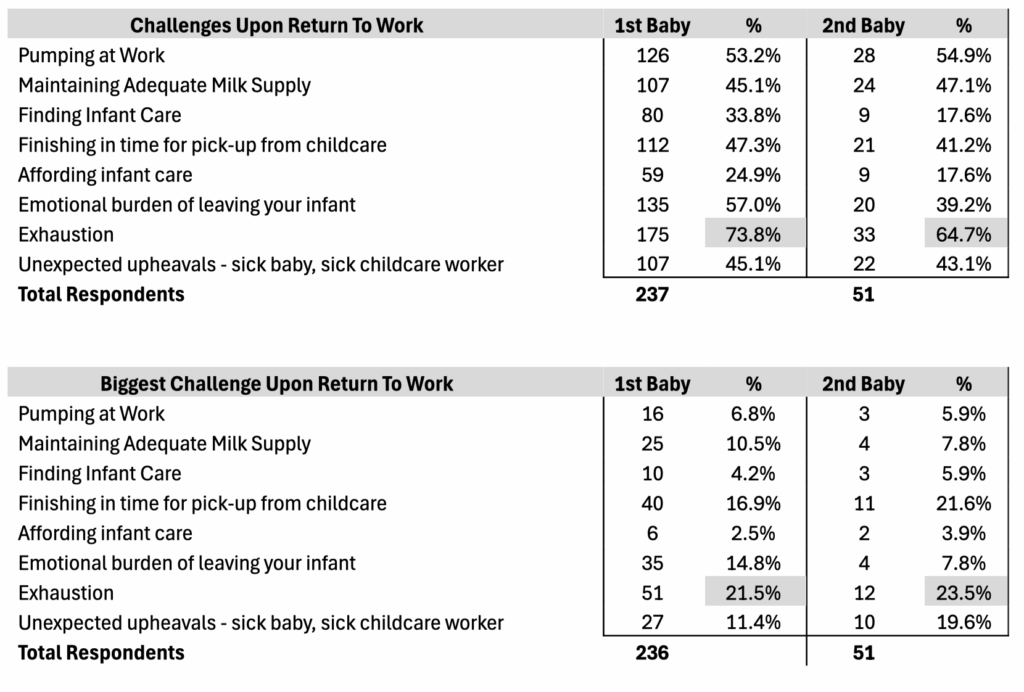

When asked about the many challenges of returning to work, first-time mothers most frequently cited exhaustion, the emotional burden of leaving their infant, and pumping at work. With second babies, exhaustion was followed by pumping at work and maintaining an adequate milk supply. The single most difficult aspect for both first- and second-time parents was exhaustion, followed by finishing their day in time to pick their children up from child care. Third was the emotional burden of leaving their infant (see Figure 7). One respondent commented, “Finishing on time while still fitting in all appointments and pumping felt impossible!” A practice owner reported, “I had a nanny come with me to work so I could continue breast-feeding but be able to hand the baby off when needed. I plan to offer this kind of child care to future employees if they want. I was still able to have a productive workday.”

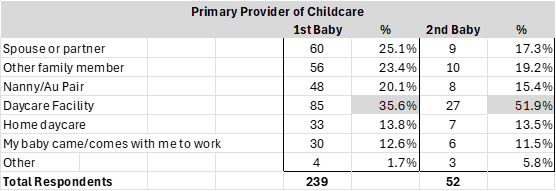

The most common primary provider of child care for both first and second babies was a day care facility. In the survey, 35.6% of respondents with one child reported using a day care service, compared to 51.9% of respondents with two children. Just over 10% of veterinarians reported bringing their infant to work with them regularly (see Figure 8).

Team Perceptions and Reactions

Veterinarians generally reported receiving positive reactions from their practice teams upon sharing the news of their pregnancies. However, these reactions varied. One respondent said, “I was told I was a burden to the other doctors, and I was put on leave early.” Another stated, “My immediate boss was thrilled and loved the news. My colleagues were not as thrilled and asked how I was going to make up my missed on-call time.” Still another said, “Family-friendly, my ass. It was like some days I was really worth protecting, but if we were short staffed nothing mattered.” One doctor said, “My boss was very inconvenienced by it, to the point of making snide comments.” Another commented, “I was fired from the job I had at the start of my pregnancy when the news was shared.” Fortunately, these experiences were rare among respondents.

Katie Coleman, DVM, reported having a very good experience at the practice where she works as an associate. “My first was born 4/2/24,” she said. “I worked until just before her due date, but stopped doing lameness about a month before and took no on-call the last three weeks. I had eight weeks off after her birth. Per my contract, I was not supposed to have maternity leave pay, but once I was pregnant, my boss told me she would pay eight weeks maternity leave anyway. She offered that I could start back to work at three days per week for a while, so I’ll probably continue this for six weeks total and then go back to our full-time regular schedule of four days/week. I don’t take pump breaks but have an awesome tech and pump in the truck or at my desk if in the office. I have felt very supported through the process and really appreciate the flexibility and support of my co-workers and boss. My husband had a one-month paternity leave through his work (corporate small animal), and having him at home too at the beginning helped the transition to parenthood a ton.”

Take-Home Message

Navigating pregnancy and maternity leave as an equine practitioner is certainly more challenging than in other professional settings because of the traditionally long hours and the need for emergency coverage. By adopting new paradigms and following the lead of some of these amazing equine veterinarians making it work, those entering the profession can feel assured that they can start a family and still have a career as a horse doctor.

Related Reading

- Parenting as an Equine Practitioner

- The Equine Practitioner’s Mid-Career Crunch

- The Business of Practice: Balancing Parenthood With Equine Practice

Stay in the know! Sign up for EquiManagement’s FREE weekly newsletters to get the latest equine research, disease alerts, and vet practice updates delivered straight to your inbox.