This article originally appeared in the Winter 2025 issue of EquiManagement. Sign up here for a FREE subscription to EquiManagement’s quarterly digital or print magazine and any special issues.

Veterinary literature reports that at least 80% of gray horses will develop melanoma after 15 years of age. Most of the tumors develop in the perineal area, tail, prepuce, parotid region, eyes, and mouth. Melanoma can also potentially metastasize to internal organs. The high incidence in aged gray horses seems to be due to a mutation in the STX17 gene.

Fortunately, small dermal melanomas that are well-circumscribed nodular lesions do not cause significant problems unless they interfere with tack or eating (in the mouth area). Many of these are left untreated under the premise of benign neglect. Recent study results, however, suggest that if nodular lesions ultimately progress—as 66% tend to do—subsequent “life-threatening issues” can potentially develop due to enlarged size and/or coalescence.

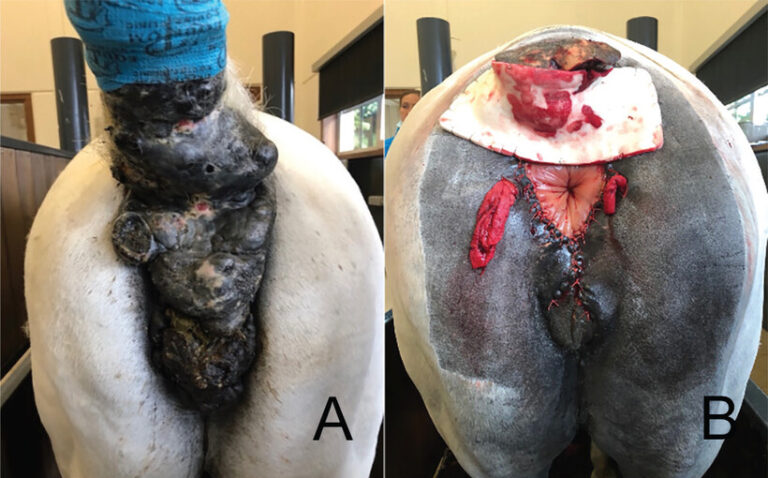

Perianal melanomas can develop side effects such as ulceration, necrosis, bleeding, infection, and pain. If lesions grow large enough, they can adversely affect a horse’s defecation and urination. Perirectal masses grow in height and length rather than width, thereby reducing the risk of rectal compression.

Research on Surgical Excision of Perianal Melanomas

Researchers in Belgium evaluated the efficacy and outcomes of complete surgical excision of perianal melanomas.

Anecdotally, some veterinarians believed surgical excision might lead to tumor activation with tumor regrowth and metastasis, the study authors noted. Equine surgeons have more recently reported that “surgical excision is a viable treatment option for melanomas that will not activate malignant behavior or accelerate tumor growth.”

Study Population

The Belgian study took place from July 1, 2020, to July 31, 2023, and included 59 horses with tenesmus, weight loss, or hind-limb lameness associated with perianal tumors. Six horses presented with no complaints. Perianal melanoma ulceration occurred in 28 horses, and 52 horses also had perirectal masses. All horses’ tails were affected.

Surgical Procedures

Prior to excision surgery, practitioners ultrasounded the abdomen and thorax to rule out internal abdominal or thoracic masses. They also performed rectal exams to check for internal perirectal masses. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia for eight horses; the other 51 patients underwent standing surgery with sedation, epidural anesthesia, and a ring block with lidocaine. Following careful dissection of a wide margin around the lesions and hemorrhage control, the incisions were closed with sutures in all but one horse. The tail was amputated in 13 cases with extensive tail lesions. Only one horse needed second intention healing because primary closure was not an option. All horses received antibiotics and anti-inflammatories for the week following surgery, were fed a mash diet, and were given manual evacuation of manure as necessary. Hospitalization following surgery lasted 3-53 days: Timing depended on horses being able to evacuate manure on their own and owners’ comfort level managing wound care at home.

Surgical Outcomes

Fifteen horses had complications (wound dehiscence, severe inflammation and edema of the rectal mucosa). Healing in noncomplicated cases took 10-14 days. With dehiscence, it took 6-8 weeks.

The researchers obtained follow-up information from the owners of 50 of the 59 study horses over six to 48 months.

- Forty-seven of the 50 horses recovered completely with uncomplicated healing; 44 experienced improvement.

- Seven horses had suture dehiscence, with complete healing by two months.

- Three retained a small, nonepithelialized scar at the tail base for 12 months.

- Recurrence developed in six horses:

- A perianal melanoma a few millimeters in size in five horses.

- One horse developed perianal and perirectal recurrence and eventually was euthanized due to weight loss and nonresponsive fever.

- Excision surgery did not impair rectal or anal function.

- In cases where melanoma remained in other areas, no horse experienced tumor activation.

- Five horses died because of reasons unrelated to the melanoma excision surgery (e.g., colic, penile squamous cell carcinoma, unknown).

- All horses returned to their intended use at their previous level of activity.

The authors noted that standing surgery allows for better visualization and improved hemorrhage control compared to general anesthesia.

They reported that perianal surgical excision is an effective treatment of large perianal melanomas, particularly in comparison to previous attempts with conservative treatment, such as radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy with cisplatin, or diode laser surgery. Timely surgical excision should obviate the need for euthanasia in most cases.

Final Thoughts

In summary, the authors said complete surgical removal of perianal melanomas is “an effective and safe technique with a good cosmetic outcome” that improves horse comfort and mitigates potential complications or metastasis.

Reference

Haegeman L, et al. Surgical technique, outcome, complications, and recurrence rate for removal of extensive perianal melanomas: 50 treated horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc May 7 2025.

Related Reading

- Kester News Hour Hot Topics: Melanoma, EHV-1, and Lyme Disease

- Equine Melanoma Treatment Research

- Equine Melanoma Update

Stay in the know! Sign up for EquiManagement’s FREE weekly newsletters to get the latest equine research, disease alerts, and vet practice updates delivered straight to your inbox.