Editor’s note: CareCredit has partnered with EquiManagement to bring you summaries of equine business presentations from the 2020 AAEP Convention. We will run two original articles per month in January, February and March, then CareCredit will help us provide in-depth AAEP Convention business coverage in the Spring 2022 issue of EquiManagement magazine.

Mike Pownall, DVM, MBA, a respected veterinarian and veterinary business consultant from Canada, remotely presented an excellent hour-long talk titled “Identifying Industry Trends and Their Effect on Equine Practice: Collaborative Practices” for the 2020 AAEP Convention. During this presentation, the speaker clearly explained the current landscape in corporate acquisitions of equine practices and questioned the financial wisdom of such sales for most practice owners. A panel discussion followed, with seven veterinarians sharing their experiences with collaborative alternatives.

The challenges of equine practice include the exhaustion and burnout of both veterinarians and veterinary staff due to practices being much busier in the last two years, Pownall stated. This increase might be due to horse owners having more time and disposable income, he said, and the result is that “practices are trying to do more work with less staff” at the same time veterinarian and staff retention in the industry has been an increasing problem. With those entering the field inadequate to replace those retiring, exit strategies for practice owners have become more difficult, he said. Increasingly, corporate sales have become the remedy of choice.

However, Pownall suggested that the decision to sell to a corporate consolidator must be made carefully. He suggested asking yourself the following questions: What is your stage in your career? Do you still love practice? Is your legacy important to you? Is taking care of your current staff and associates’ future something that concerns you? What is best for the equine veterinary profession?

“This profession has done well financially for many practice owners,” Pownall said, “and shouldn’t the next generation have the same opportunity?”

Understanding Valuation

Different types of exit strategies could be a sale, a merger or formation of a management company. These all include the need for a valuation. Often value is stated as a multiple of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization), after standard adjustment of the financials, said Pownall. The multiple is related to risk. In the past, equine practices were typically sold for a 4-5x multiple (four to five times the EBITDA), but now corporate aggregators typically buy at a multiple of 10-15x EBITDA, he stated. An increased multiple represents a perception of decreased risk. Because a practice with just 1-2 doctors is more risky, the value is lower. This risk is related to insecure cash flow if one of the veterinarians is injured or leaves the practice. In bigger practices, the revenue is produced by more people, so the loss of one veterinarian can often be absorbed by the team, so risk is lower, he stated.

To maximize the value of a practice, Pownall recommended increasing EBITDA, decreasing risk to increase the multiple and decreasing debt (as liabilities are subtracted from the purchase price).

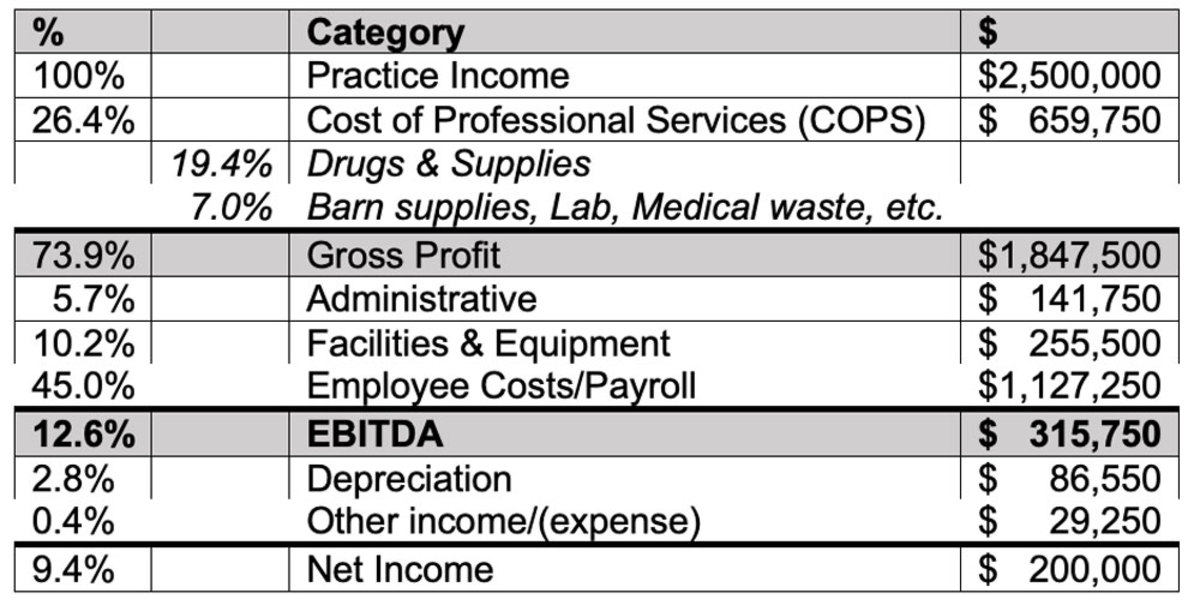

As an example, he demonstrated a concise profit & loss statement of a hypothetical practice based on John Chalk’s benchmarks derived from a group of 30 equine practices (see Figure 1). If this practice produced $2.5 million in revenue with an EBITDA of $315,750 and had no debt, he said, at a multiple of 10 the practice would be worth $3.16 million. At a multiple of 5, as is typical in sales to associates, the practice would be valued at $1.58 million.

“Is it any wonder that practice owners sell to corporate?” he asked.

Boost Practice Value

To boost value, a practice can increase their EBITDA by increasing revenue. The easiest way to do this is by raising fees. With current inflation, he suggested that all practices must increase their prices just so their EBITDA doesn’t fall.

Other methods to increase profit are to decrease expenses by shrinking inventory and to keep staff members happy and engaged so they stay with the practice (recruiting and training is expensive). If the practice receives a lot of cash payments, they must be recorded as income, he said, or this revenue will not contribute to the value of the practice. Likewise, if any of the owner’s personal expenses are run through the business, they must be well tracked so they can be easily removed when a valuation occurs. In addition, under- or over-paying veterinarians for their work must be adjusted to mirror the reality in the marketplace.

Consistency in EBITDA and revenue is one of the most important factors in risk assessment, Pownall stated. This consistency is observed typically over 3-5 years, and a “yo-yo effect” is bad, he said. Other factors that decrease risk (and thus increase value) are consistent staffing, an excellent reputation and client loyalty.

Understanding Corporate Buyers

Corporate consolidation in the equine space has increased dramatically in the last 2-3 years, he said. Corporations typically are interested in practices with at least 3-4 veterinarians because this increases revenue and decreases risk.

“Where does the money come from to pay these huge multiples?” he asked. It comes from the Private Equity Aggregation Model. Pownall then explained how that works.

A Private Equity firm (PEF) accumulates a fund of capital from institutions (such as pension funds or colleges) or high-value individuals, attracting their investment by promising a sure profit over a 4-6 year period. To provide this return, the PEF must grow revenue and increase profitability in the practices they buy.

When purchasing, the firm offers the seller an exit strategy, economies of scale (which might or might not come to fruition, as veterinary practices typically are frugal already), staff recruiting, and back office support such as HR, marketing and bookkeeping. They do not offer direct management, the speaker said, which means “the headache doesn’t go away”.

Although they often promise a personal approach, it is almost always less so than they claim, he added.

It is also important to look for a “drag along clause” in the fine print of contracts. This clause allows all shares to be sold in the future without all shareholders’ consent, meaning that young associates who purchase a small amount of shares at the time of acquisition might not still be owners upon the next sale.

As the PEF accumulates the fund, they take 2% to pay salaries of the consolidator team and 20% of the profits. 80% of the profits are returned to the investors.

Typical initial consolidators acquire a practice for 10-20x EBITDA, then increase the revenue and decrease the expenses. Because it takes the same output of energy to run a practice grossing $10 million as it does to run one grossing $1 million, aggregators prefer bigger practices.

Next, they nurture the practices to higher profits, trying to bring EBITDA to 20%. In this phase, requests for new equipment or additional staff typically go unanswered, as efficiency and high productivity from existing assets increase profit more than additional capital investment in the short term, he said.

Typically, the next sale of the practice will occur in about 5 years in order to give the original investors the promised 20-30% return on investment.

Pownall raised the question, “Is this a good thing for the equine veterinary industry?”

In the stage of acquiring the practice, the sellers are induced to stay working in the practice for 1-3 years. They receive 75% of the sale price upfront and the remaining 25% if the practice hits the expected performance targets. Often associates are offered a small number of shares to ensure their retention. Even at this stage, the PEF generally know who they will be selling to next. “They have talked to the bigger fish,” shared the speaker. “They are in the business of selling at a higher value—that is the primary goal.”

Unlike veterinarians, whose primary goal is doing what’s best for their patients and clients, a PEF has to deliver on their promise of high return or their reputation suffers.

In the nurture phase, typically the sellers have departed and the work to squeeze cost savings and increased profit begin in earnest. The consolidator is preparing to sell at a higher value, Pownall stated. Despite good relationships that might have developed with the aggregator management team during these initial years, once the next sale occurs, the veterinary team will have new bosses and perhaps new policies. With the goal of such a high ROI (return on investment), “what will happen when there are no next buyers?” he asked, describing one Scandinavian country where all the equine practices were purchased by one aggregator who subsequently five years later sold them back to the veterinarians at 50% of the price they initially paid. “Being bigger doesn’t necessarily mean more stable,” he concluded.

However, there are corporate veterinary practice owners that are not fueled by private equity, said Pownall, and these are some of the biggest. Mars Incorporated is a privately held multinational manufacturer of confectionery, pet food and other food products and a provider of animal care services, with $40 billion in annual sales in 2020. Fifty percent of this family-owned company’s revenue is in pet health care and nutrition. Antech Diagnostics and Sound became part of Mars in 2017, he added. The AniCura group is similar in Europe.

The very high multiples that are paid by big corporations are related to the decreased risks when buying a group of practices that have already been curated by a smaller aggregator, said Pownall. If one practice is experiencing lower profits, it is likely another in the group is earning higher EBITDA. This diversifies the risk. In addition, systems are already in place to manage the practices as a group. “The hard work has already been done,” Pownall said.

Fear of Missing Out

He also highlighted the “fear of missing out” that is common among younger practice owners from their 30s to early 50s. He described the partner disruption that can occur when an older partner wants to cash in with a corporate buyout, but the younger partner doesn’t agree. For some, the disruption and aggravation of the pandemic have made owners of all ages ready to sell. To help owners make a rational decision, the speaker outlined an example to compare selling a practice now to a corporate aggregator versus keeping it for another 10 years.

Selling a practice with a $1-million revenue and 15% EBITDA would yield a selling EBITDA of $315,750, which if sold for a multiple of 15 would give a sale price of $4,736,250. If that money were invested with an annual investment yield of 5%, and the seller received a salary of $130,000 for his last three years of work and he withdrew 4% of his investment per year to live on, over 10 years he would have an investment return of $5,751,296 and three years of salary along with the 4% withdrawals of $1,974,341 for a total of $7,725,637.

In contrast, if the owner kept the practice an additional 10 years and grew the revenue by 5% a year, with an EBITDA of 15%, final sale multiple of 10, and annual salary increases of 3%, he would receive $4,923,404 in cumulative EBITDA, cumulative salary of $1,490,304 and a sale price of $6,205,313 for a total return of $12,619,021. This is a difference of $4,638,009 the speaker stated. “And who couldn’t use an extra $4 million?” he quipped.

Take-Home Message

In concluding, Pownall stated: “Why are we giving away the value of our practices when we have a long professional lifespan ahead of us?”

Instead, he recommended considering models to collaborate with other practices to increase success for all.

(Editor’s note: Watch for a future article on these collaboration models. Also, keep in mind that not all corporate collaborators are the same; some practice owners have been pleased with their corporate sales and not all “corporate” buyers are purchasing practices to resell. Make sure you do your homework and talk to others before you make a decision.)

This content is subject to change without notice and offered for informational use only. You are urged to consult with your individual business, financial, legal, tax and/or other advisors with respect to any information presented. Synchrony and any of its affiliates, including CareCredit (collectively, “Synchrony”), make no representations or warranties regarding this content and accept no liability for any loss or harm arising from the use of the information provided. All statements and opinions in this article are the sole opinions of the author and roundtable participants. Your receipt of this material constitutes your acceptance of these terms and conditions.

Brought to you by CareCredit