Credit: Thinkstock

Credit: ThinkstockYou’ve just finished another very long day of work and you’re looking forward to changing out of your dirty clothes, then diving into some good food and drink and putting your feet up for the remainder of the evening. It’s a familiar scenario: You walk into your house, drop the truck keys on the table, and get about five steps toward your closet when “beep-beepbeep” or “ring-ring-ring,” there goes your pager or smart phone.

Dutifully and out of habit, you call your client to find out what warrants an evening contact. Sure enough, she just got home from dinner out with friends (you haven’t yet had any dinner, or lunch for that matter!) and went to the barn to give a goodnight pat to the horses. Looks like one of them has incurred a laceration on the face and, fearing a cosmetic scar, the owner wants you to come out. Now.

Most of us know that facial injuries heal quite fine even if not addressed within the initial few days. Your client gives you a careful description of what she’s looking at, and you ascertain that it’s a two-inch wound most likely only through the skin and far from any important structure. But, from your client’s point of view, she sees this two inches as a gaping hole filled with blood and marring her horse’s beautiful perfection.

So, how do you handle this or any similar situation that is perceived as an emergency by a client—but isn’t, in your medical opinion?

In other issues of EquiManagement, finding a work/life balance has been an ongoing theme. Without discriminating as to what is and what isn’t an emergency, you could find yourself working almost around the clock, which is a fast path to burnout.

How do you explain to your clients what justifies a crisis that warrants you dropping everything—your meals, your family, your friends and your precious personal time?

Education

The process of bringing your clients into touch with the reality of what is and isn’t an emergency isn’t going to happen in one discussion with them. It will take a little work on your part, but it can be accomplished through education.

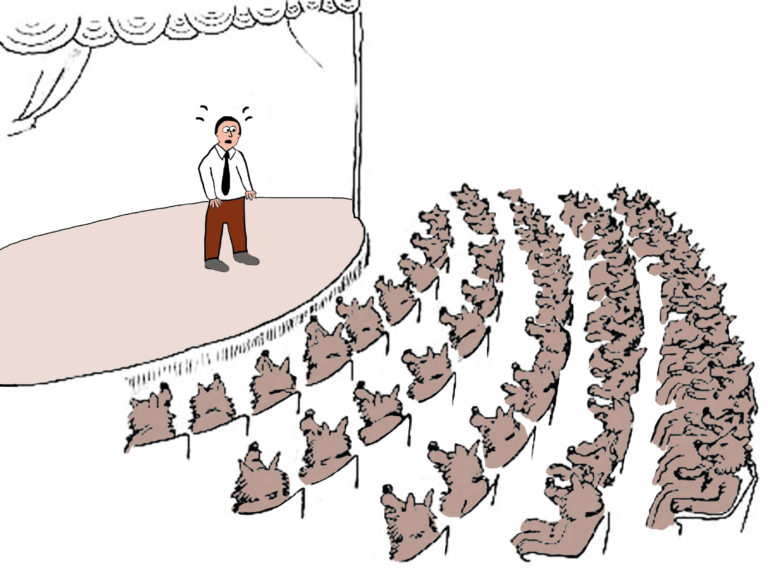

An excellent means of educating is putting together a seminar on the topic of emergencies, complete with photos demonstrating the differences between situations that are true emergencies compared to problems that can safely wait for several hours or until the next day. (Editor’s Note: This issue’s cover story “Host an Educational Event” can help you learn how to put on a client seminar.) Having conducted such seminars, what I found particularly interesting is the large number of people who showed up. I also discovered that the packed audience included far more horse owners than just my clients. After delivering these presentations, I saw an immediate reduction in the number of non-emergency “emergency” calls; this relief has persisted for 12 years!

Note of caution: If you want to be involved in every little aspect of your clients’ concerns— no matter how trivial— and you rely on generating income from a busy emergency case load, then don’t hold a seminar to teach them, because your after hours case load will diminish.

Many clients really want to learn. You are the best resource to provide the information they need. If you’re in a busy practice, it helps ease your night and weekend load when they are capable of cleaning a wound, safely and effectively bandaging a leg or foot, and gathering vital signs. By learning these basic skills, your clients become more clinically minded when observing a horse’s plight and thus less prone to panic.

By improving the efficiency of your workload and ensuring rest and time for your personal life, you’ll be fresher at work each day. Having a bit more time at hand enables you to focus on true medical problems and facilitates more time to be devoted to complicated cases.

What are True Emergencies?

Certain conditions do necessitate a fast response, particularly when you are dealing with a client who isn’t very knowledgeable:

- Colic

- Choke

- Eye trauma

- Acute onset severe lameness (anything from laminitis or nail puncture to hoof abscess or fracture)

- Acute musculoskeletal swelling and lameness, especially if associated with joints or tendons

- Lacerations or punctures over a joint or tendon

- Lack of appetite and/or fever; in general, the horse is ADR (ain’t doing right)

- Hemorrhage

- Neurological problems

- Respiratory distress

- Reproductive emergencies such as dystocia, post-foaling hemorrhage or uterine prolapse

- Foal emergencies such as failure to nurse, colic, meconium impaction or septicemia

- Snake or dog bite

No doubt there are other situations that could be included on this list, but this is a starting point for acknowledging conditions that probably should be seen day or night as soon as the owner discovers the problem.

Client Skill Set

Working with your clients’ basic skill sets is one of the best means of dispelling some of their fears when faced with an equine medical problem. Teach them how to gather vital signs, how to clean a wound and which supplies are best to use. Teach them some tricks to try for colic, like a 10-15 minute trot in the round pen to see if that alleviates intestinal gas or spasm. Remind them to check for a nail in the foot or to look for an area of swelling when the horse is hobbling around. Teach them how to apply a pressure bandage to control hemorrhage and how important it is to not to disturb clot development by continually peeking beneath the bandage for the first 15-20 minutes.

Gathering information is what owners can do best as they are on-site with the horse. Then they’re able to relay this to you via phone and/or email or text images, enabling you to be more capable of making an informed judgment as to the seriousness of the condition. Based on the working relationship you’ve had with particular clients over the years, you’ll have a feel for who is able to transmit accurate descriptions and who is likely to miss important details.

In addition to your hands-on educational approach, you can also refer your clients to handouts and other reading material. Be prepared for them to ask questions to satisfy their curiosity. Making yourself approachable and available assures them that you are there to help.

Ongoing Communication

Despite the desire to provide clients with know-how and basic skills, you don’t want them to fail to contact you when there is, in fact, a crisis. It gives them a great measure of confidence when they are advised that they should continue to call you with any questions if there is even an inkling of doubt about the problem they have encountered. You want the owner to call about a horse that is choking rather than the owner thinking the horse has a respiratory infection that can wait until morning.

Again, that is the importance of clear and concise educational information that helps a horse owner decide when it is best to call and discuss the horse’s problem with you.

With a phone discussion, you’re able to ask appropriate questions to garner details from your better-educated horse owner. The ease with which we have telecommunications and email available to us these days can aid vets in freeing up a lot more time. Staying in touch 24/7 might seem somewhat intrusive, but not as intrusive as running off in the ambulatory truck to every perceived crisis, only to find that the colicky horse on a Sunday morning wouldn’t eat because he was simply in need of some overdue dental work.

Take-Home Message

Keeping in contact with your clients still keeps you in the driver’s seat for discerning what constitutes a real emergency, so you aren’t carrying on a “fire engine” practice that creates non-stop demand with little relief. Helping your clients be more in touch with the reality of emergencies then becomes a team effort on the part of horse owner and veterinarian. You benefit by freeing up some quality personal and family time and by feeling more rested. Your client benefits from this communication through pocketbook savings. But most importantly, the horses are the ones that benefit most when veterinarians and horse owners communicate well.