Just the word “negotiation” makes most people cringe. When most veterinarians think about negotiation, they think of bargaining with a salesman over the price of a new digital radiology unit or dickering with a car salesman over the price of a new vehicle. The truth is that negotiations take place continually in life: between business owners and employees, vets and horse owners, parents and children. Any time a decision requires input from more than one person, negotiation is involved.

One can define negotiation as the process by which two or more parties attempt to resolve their differing interests. Some things are common to all negotiations, whether they are between warring countries or between a parent and child: Negotiation occurs between two or more parties that have a conflict of needs, desires or interests that need resolution. The parties negotiate by choice, voluntarily, because they feel they can gain a better outcome than by simply accepting what the opposing party is offering. The parties prefer to negotiate rather than fight or sever a relationship. They prefer to bargain rather than have one of them dominate and the other one capitulate. They prefer to try to figure out their conflict themselves rather than take their dispute to a higher authority for resolution.

One essential fact about negotiations is that in order to be successful, both parties must move from their opening positions in order to reach an agreement. In addition, good negotiators manage intangibles as well as tangibles. This means that besides money and goods, all parties’ emotions, pride, reputations and relationships are considered. These factors can be remarkably important in preserving relationships for the future.

A critical concept for all negotiators is BATNA, or “best alternative to negotiated agreement.” Understanding the best alternatives if a negotiation fails is important, because negotiators who have considered their options have much more power to walk away from a deal that is not attractive. Knowing the best alternative to an agreement before entering into a negotiation is critical to making good decisions. Because of their awareness of their true “bottom line,” negotiators with a firm understanding of their BATNA have power and confidence, and are generally more successful in achieving their goals.

Types of Negotiation

Some negotiations are zero-sum or distributive , while others are mutual-gain or integrative . Distributive bargaining is a competition over who will get more of a limited resource. This type of bargaining occurs when the goals of one party are in direct conflict with the goals of the other. Integrative negotiation is a collaborative, cooperative activity that aims to allow the needs of all parties to be met.

Distributive Negotiation

Because distributive bargaining generally focuses on haggling about a price and is competitive, both parties’ interests are in direct conflict. There is a fixed resource (often money), and both parties are seeking to maximize their gain.

Because these negotiations result in a winner and a loser, using distributive tactics should be reserved for situations where either a single, simple deal is being made and a future relationship with the other party is not important, or an integrative negotiation has progressed to the point of each side “claiming value.” (“Claiming value” is the actual divvying up of the resource over which the negotiation centers. Who gets the biggest piece of the pie? Or who gets pie and who gets cake?) A vet purchasing a used truck from a car salesman should use distributive bargaining techniques.

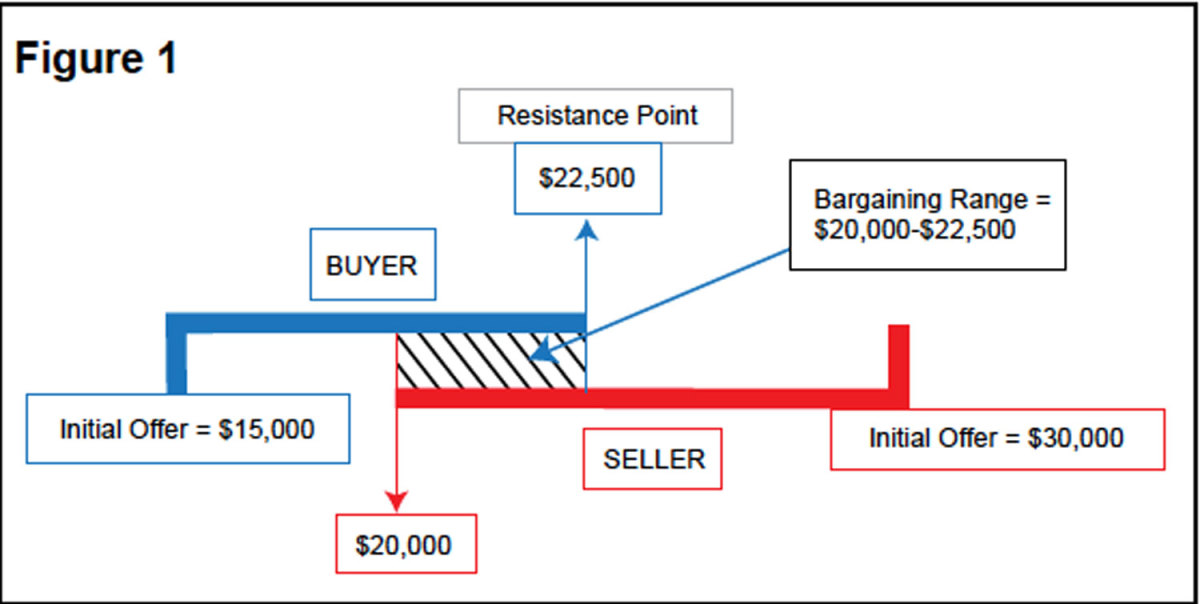

In distributive bargaining, each party has a goal regarding the optimal point at which negotiations will conclude. This is called the target point. Each party also has a resistance point, beyond which he or she will break off negotiations and walk away.

The opening offer will serve as an anchor for the negotiation. The anchor point is very important, because all negotiation will take place around this initial stake in the ground. If opening offers (whether from seller or buyer) are too far from the target point, it is possible that no negotiation will occur. For instance, if the used truck salesman states that the truck’s price is $35,000 but the target point of the prospective buyer is $15,000, it is quite unlikely that a negotiation will occur; the buyer will assume he or she can’t afford the vehicle.

The spread between the buyer’s and seller’s resistance points is known as the bargaining range, because any offer outside of this range will be immediately rejected by the other party. If the salesman’s lowest acceptable price (his resistance point) for the used truck is $20,000, he will dismiss an offer of $15,000. Through the process of making offers and counter-offers, each party begins to reveal his or her resistance point.

Consider a seller with an opening price of $30,000, a target of $25,000 and a resistance point of $20,000 bargaining with a buyer with a target of $17,500 and a resistance point of $22,500. One can see that the bargaining range is between $20,000 and $22,500 (see Figure 1). Within a few minutes of conversation, each party will understand the other’s position better, and a deal might be made that satisfies both.

A positive bargaining range occurs when the buyer’s resistance point is above the seller’s, so there is room for a mutually agreeable price to be reached. In the case of a negative bargaining range, the seller has a minimum price that is higher than the maximum that the buyer is willing to pay. In this case, the negotiation will end, the parties will re-think their resistance points, or the buyer will pursue an alternative.

The concept of BATNA is very important in distributive negotiation. If the vet has identified another used truck at another dealership with an asking price of $22,500 (that party’s BATNA), he or she will be much more likely to press the salesman for a sale price on the subject truck that is closer to his or her target, and less likely to agree to a price close to his or her resistance point.

The basic strategies in distributive bargaining are to push for a price very close to the seller’s resistance point by making extreme offers and small concessions, and/or to convince the seller to reconsider his or her resistance point by influencing that party’s beliefs about the value of what he or she is selling. For instance, if you are buying a used truck, and it has a small dent, you might say, “Too bad the truck has this dent. Did you notice that?”

During negotiations, it is best if you can get the other party to make the opening offer, because then you will have some idea of what that person’s bargaining range is. Because concessions are essential, if you must make the opening offer, make sure it is sufficiently distant from your resistance point to allow room for an exchange of offers.

Research shows that parties are more satisfied with agreements if there is a series of concessions rather than if the first offer is accepted. If there is no bargaining, often people feel as though they could get a better price elsewhere, and they might walk away. When making concessions, one can determine when a counterpart’s resistance point is being reached as successive concessions become smaller.

We all know people who approach all discussions as though they were bargaining sessions, and they generally are not people who are enjoyable to be around. By reserving this approach for situations that are truly one-time transactional agreements with no relationship components, you will have the most rewarding results.

Integrative Negotiation

In integrative negotiation, the goals of the negotiating parties are not mutually exclusive—this is win-win bargaining. In this negotiation, there is a focus on what is found in common rather than on differences; on meeting the needs of all parties; and on an enlargement of the pie through innovative ideas. To be a successful integrative negotiator, one must build trust through integrity; have a positive outlook that sees abundance rather than scarcity; recognize that others’ interests have equal value to yours; be able to see the big picture; and have strong listening skills.

By facilitating a reciprocal flow of information, both sides gain understanding of the needs and concerns of their counterparts, leading to less extreme resistance points. Identification of the others’ true objectives and desired outcomes can lead to recognition of common ground and areas of alignment. This makes searching for solutions that meet both sides’ goals more successful and satisfying. By generating multiple alternatives, innovative solutions can arise that increase overall value.

As an example, “Dr. Jane” is an associate who would like to pursue acupuncture training, but the required tuition and time away exceed her contractual continuing education budget and allotted days off. An active dialogue is needed between “Dr. Jane” and the owners of the practice that focuses on understanding the costs, benefits, goals and threats of this desire. By defining all the parameters of this “problem” collectively, both the associate’s and the practice’s needs and priorities can be accurately identified.

A collaborative approach that allows all concerns and aspirations to be voiced is most likely to produce an agreement that honors the needs of all parties.

One can imagine the associate’s poor morale if the request was simply denied—or the practice owner’s feelings of betrayal if the associate departed after the practice financed her training, and there was no repayment clause.

Both parties must think of what their BATNA is in this situation. The associate’s BATNA might be to pay for the training herself and utilize vacation time in order to attend. The practice’s BATNA could be to give the associate unpaid leave to attend the course, with her assuming all expenses in excess of her continuing education budget. When assessing these BATNAs, it is clear that a negotiated settlement is likely to be more satisfactory for all parties.

Steps for Integrative Negotiation

A sequence of steps for an integrative negotiation can be followed through collaboration:

1. What is the problem?

a. Depersonalize it.

b. State the problem as a specific goal to be attained.

c. Explore all possible aspects of the problem.

d. Explore all related issues.

e. What is most important? What is least important?

2. What obstacles must be overcome to achieve the goal?

3. What interests are present?

Interests are underlying concerns, needs, desires and fears that motivate a negotiator to take a particular position.

a. Are they substantive (related to the focus of the negotiation)?

b. Are they process-oriented (related to how the negotiation unfolds)?

c. Are they relationship-based (related to value placed on relationships)?

d. Are they interests “in principle” (related to fairness or values)?

4. Explore why they want what they want.

5. What criteria will be used to judge proposed solutions?

Parties need to agree on criteria before generating solutions.

6. What are possible solutions to solve the problem?

a. Generate multiple alternatives.

b. Avoid judging or evaluating solutions while brainstorming.

c. Avoid ownership of solutions.

d. Ask outsiders.

e. Attempt to expand the pie, creating additional value.

7. Evaluate solutions on the basis of the criteria previously determined.

a. Narrow choices by rank ordering.

b. Judge solutions by how good they are and how they will be accepted by those implementing them.

c. Consider combining options into packages that please multiple interests.

d. Try to reach consensus rather than voting; this will help create full commitment by all parties for the implementation of a negotiated settlement.

8. Formalize the agreement in writing.

Negotiation Styles

Different individuals have innately preferred negotiating styles. These include inclinations toward accommodation, compromise, competition or collaboration. By understanding one’s own preferences and being aware of the potential for others to have differing styles, you can negotiate more effectively.

As you become more comfortable with experimenting with other negotiating styles, you will gain even more skill at bargaining. A cooperative approach is often more effective than a competitive one, and awareness of personal preferences can lead to better outcomes.

Simple assessment exercises are available that reveal preferred negotiating styles. Dr. G. Richard Snell, a professor at the Wharton School of Business, created an assessment tool for negotiation style that is printed as an appendix in his book “Bargaining for Advantage.” Results of this assessment can reveal a preferred style of negotiation. Gender and culture also play a part in negotiating styles.

Accommodation

Those with a strong accommodation style have strong skills in relationship building and enjoy helping solve others’ problems. They can excel in many customer service roles and integrative bargaining situations, but they can be vulnerable to competitive counterparts.

They might sometimes place more value on relationships than is warranted by the situation. Those with weak accommodation skills often focus on being “right” and have difficulty seeing other perspectives. Others might see them as stubborn and unreasonable or uncaring about others’ feelings.

Compromise

Negotiators who are predisposed to compromise are eager to find an agreement that will close the negotiation. Seen as friendly and reasonable, compromisers often grasp the first fair solution that presents itself and are vulnerable to choices made without adequate fact-finding.

Those low on compromise abilities often have strong principles and passion, but are subject to standing on principle when common sense dictates otherwise; they can be seen as stubborn.

Avoidance

People that favor avoidance dislike confrontation and will dodge all situations that lead to disagreement. This can manifest as diplomacy and tact, and can be very helpful in tense negotiations. Conflict avoidance, if well handled, can bring difficult groups to agreement.

However, important information is often not brought into the open due to a fear of difficult conversations. Those who have low avoidance preferences have a high tolerance for assertive or even aggressive conversation. They are often seen as lacking tact or being overly confrontational. However, they can be valuable in some bargaining situations.

Competition

Negotiators who prefer competition like to win, and they enjoy negotiating because it provides a contest. Although highly skilled in the processes of negotiation, their style is dominating and can damage relationships.

Because it’s difficult to assign value to intangibles, they often focus on the tangible aspects of bargaining, leaving value on the table. Those who have low and trust, but because they are seen as non-threatening, they will be at a disadvantage in some situations.

Collaboration

Those who are prone to collaboration enjoy solving tough problems through negotiation and work hard to find a best solution. When negotiations reach “claiming-value” stages (who gets cake and who gets pie), these people might fail to gain their share of the resources due to their wish to build consensus, and they are vulnerable to competitive negotiators.

Those low in collaborative instincts prefer a more controlled, detail-oriented process and might lose clarity and focus in the seeming chaos of a group setting.

Strategies for Negotiations

Although people have preferred styles, becoming comfortable with recognizing, working with and practicing other styles is important, as your counterparts in negotiation might have a different preferred style. Depending on the bargaining situation in which you find yourself, your style might help you be more successful, or it could be a source of weakness. Self-awareness can help you mitigate the negative effects and capitalize on the positive.

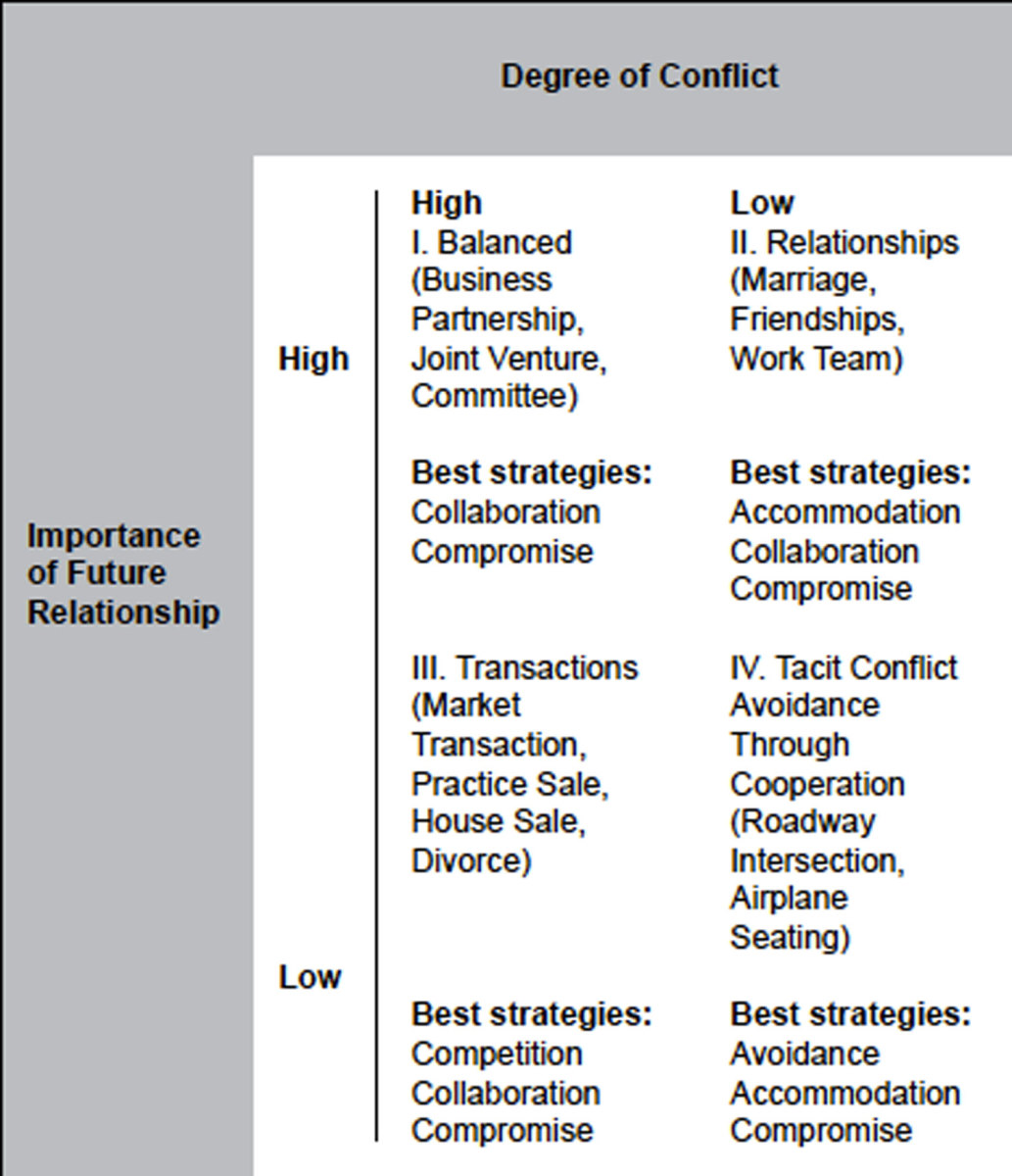

Strategies for negotiations can be chosen from a model that balances the importance of future relationships with a perceived degree of conflict. Used along with self-awareness of your preferred negotiating style (see below), one can confidently take an approach to resolving differences using recommended strategies. You can use the following chart to determine the best strategy.

You will notice that the strategies listed mirror the styles discussed earlier. In the broader categories of cooperative and competitive strategies, both have strengths and weaknesses and can be effective in different circumstances.

However, multiple studies have shown that the most successful negotiators— even in professional settings such as union negotiations—are cooperative rather than competitive. This is reflected in the preference for cooperative strategies in the rubric above.

Take-Home Message

All successful negotiations require careful preparation, including determination of the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), the target point, the resistance point and the opening offer.

Integrative bargaining requires additional steps. Negotiators must carefully define the problem, identify both parties’ needs and interests, then collaboratively generate alternative solutions. After careful deliberation of the value created by the choices generated, negotiators must then select a solution collaboratively that maximizes the outcome for all.

Negotiation is unavoidable, and it takes place regularly during the ordinary events of our work and personal lives. Understanding the difference between distributive and integrative negotiations, knowing our preferred negotiation styles, being familiar with the process of an effective negotiation, and understanding the best strategies for different situations all can contribute to negotiation with more satisfying outcomes.