During his time as resident veterinarian at Claiborne Farm near Paris, Kentucky, from 1948 through the 1980s, Col. Floyd C. Sager was widely recognized as one of the leading equine practitioners in the world. Late in his career, Sager agreed to a series of interviews with The Blood-Horse magazine to discuss the theory and practice of veterinary medicine and his legacy in the field. Those interviews later were compiled in “Col. Sager, Practitioner,” a slim volume that nearly 40 years later still shows up on the bookshelves of prominent researchers and veterinarians.

Sager took a pragmatic approach to new research. He wanted to be far enough ahead of the research curve to take quick advantage of new products and techniques, but not so far in front that he was the first practitioner to use something relatively untested.

“I always want to be the second veterinarian to try something new,” he said. It was good advice both then and now.

Traditional peer-reviewed journals, those available by subscription either in print or online, typically have rigorous standards for acceptance and publication. These journals have been the gold standard for reliable information for years, fulfilling the role of Sager’s “first user” for prudent practitioners.

However, the academic publishing landscape has changed significantly in recent years with the growth of the internet and the proliferation of “open access” journals, and finding reliable guidance in the literature is harder now than it once was. These are not to be mistaken for the “open-access” articles that legitimate journals often share.

The idea behind open access is a good one: new research distributed quickly online at no cost to readers. Mismanaged, however, open access journals can create more problems than they solve.

Open access journals are published online only and are freely available to anyone with no paid subscription required. These journals often follow a pay-to-play business model. Without subscription fees to cover the publishers’ bills, open access journal authors subsidize the journals themselves by paying high—sometimes exorbitant—publication fees. In the publish-or-perish world of academia, a hefty fee to guarantee publication of research in an open access journal often is a reasonable price to pay for career advancement.

Pay-to-play is not necessarily bad in the research publishing world—traditional subscription publishers might also charge authors a fee to help cover pre-publication expenses. But if an open access publisher relies on collecting hefty publication fees from authors to show a profit and at the same time plays fast and loose with the generally accepted standards for review to increase the number of articles published, there’s a credibility problem.

Publications that operate like this are called “predatory journals” for their high-pressure sales tactics and lack of transparency.

This doesn’t mean that research published in open access journals is always questionable; the great majority of that research is reliable.

However, it does mean that research published without the usual editorial oversight and peer review deserves a second look.

FTC Investigation

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is taking that second look at one prolific open access publisher with hundreds of journals under its umbrella. The FTC investigation is based on allegations of deceptive business practices and not on the quality of the research being published, an important distinction for practitioners in search of reliable information. But if the allegations prove to be true, and submitted articles were not subjected to the usual peer review before being rushed into publication, distinguishing between good and unreliable research becomes problematic. The result is a new level of uncertainty for veterinarians trying to evaluate research about a new product or technique.

On August 25, 2016, in the United States District Court for the District of Nevada, the FTC filed a civil complaint against open access publisher OMICS Group Inc. and associated companies iMedPub LLC, Conference Series LLC and Srinubabu Gedela, the companies’ founders. Grounds for the complaint are alleged violations of Section 5(a) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or business practices.

In various court filings, the FTC claims a litany of deceptive business practices, including:

- false or deceptive statements made on the defendants’ websites and in solicitations that they follow widely accepted peer-review practices and that all articles are peer reviewed prior to publication;

- false or deceptive statements that their online journals are reviewed and/or edited by thousands of scientists, researchers, academics and other subject-matter experts;

- false or deceptive claims that their journals have “high impact factors,” an industry standard of reliability based on the number of times articles are cited in other research;

- false or deceptive statements alleging that their journals are included in well-established and reputable indexing databases;

- harm from defendants’ refusal to allow authors to withdraw articles from publication in their journals because the practice effectively prevented publication in another journal; and

- false or deceptive marketing of academic conferences.

In responsive pleadings, the defendants argue that the FTC’s allegations are “misguided and without merit” because there was nothing either unfair or deceptive about their solicitation of articles from qualified authors. Nor, they argue, is there anything either unfair or deceptive about the way they marketed and conducted international scientific conferences or about the way they disclosed and charged fees for publication in their journals.

On September 29, 2017, U.S. District Judge Gloria M. Navarro issued an order granting the FTC’s motion for a preliminary injunction prohibiting misrepresentations by the defendants regarding publishing services and scientific conferences.

On May 1, 2018, both the FTC and the defendants filed motions for summary judgment, arguing that there were no material facts to be decided by the court and that the respective parties were entitled to win as a matter of law. Litigation in the case, including a decision on the competing motions for summary judgment, remained ongoing at the end of 2018.

Dr. Google

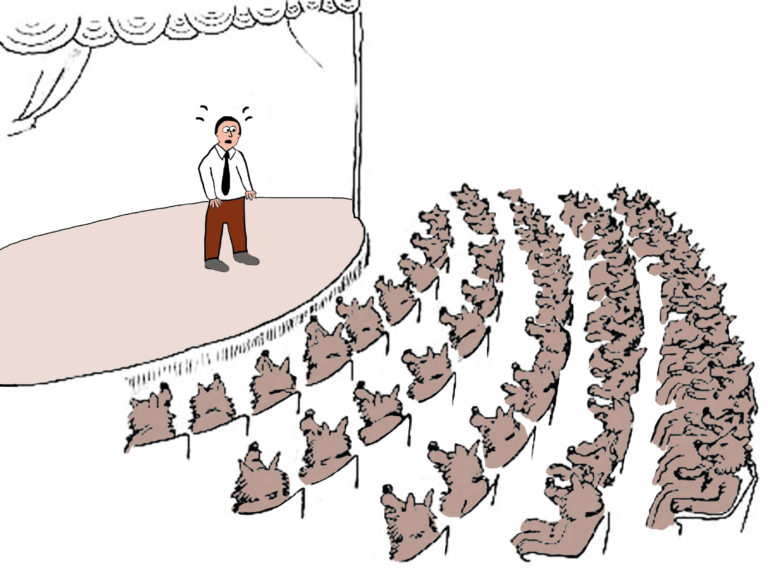

Predatory journals are a concern for academic authors and researchers. For practicing veterinarians, these journals raise two related—but probably less obvious—issues. First, distinguishing the good research from the unreliable becomes more difficult. Secondly, practitioners often must deal with clients who request a particular drug or treatment based on internet searches and news reports that promote unreliable or premature research.

In a December 16, 2018, article in The New York Times—“Dr. Google Is a Liar”—cardiologist Haider Warraich warned that the proliferation of false medical information and other “fake news” on the internet is dangerous because it steers patients away from evidence-based treatments. While the author was writing about problems with reporting research in human medicine, the things that he said patients find attractive about internet advice equally apply to a veterinarian’s clients. There is no appointment or a long wait to see a doctor, the information is free and the websites look reliable and are easy to understand.

For their own professional education, and to explain to a client that the internet is not always correct, a veterinarian’s ability to critically evaluate the reliability of published research is invaluable.

Adrian K. Ho, director of digital scholarship for the library system at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, teaches workshops that show authors how to identify and avoid predatory journals. His advice for veterinary practitioners is this: You should “play the role of a reviewer” when evaluating the reliability of an article published in an unfamiliar journal.

When evaluating an article, “look at the authors,” Ho advised. “You should ask: Who are they? Where are they from? Are they well known in their fields? Does the content in the article make sense? Are there conflicts of interest?” He added that it’s important to look at the data and how it was gathered and handled. If questions remain, Ho suggested that practitioners take advantage of the veterinary community’s “collective wisdom” by discussing the article with colleagues or through a specialty Listserv.

Ho’s workshops in journal evaluation and selection include a handout with several red flags often associated with open access journals:

- a lack of information about the scope and policies of the journal on the publisher’s website;

- negative comments about the journal from colleagues, researchers and scholars;

- minimal instructions or editorial guidance for authors;

- little or no specific information about the journal’s peer review process or alternative procedures for quality control;

- information about copyright ownership of a submitted article;

- contact information that is either missing or difficult to find;

- a website, the journal or communications from the publisher that are “fraught with misspellings, grammatical errors, broken links and/or other signs of subpar site management”;

- published articles that are written by repeat authors or editorial staff

- journal promotion involving spamming potential authors and readers; and

- obtrusive advertising on the publisher’s website.

It’s worth noting that many of the practices on Ho’s warning list are similar to the claims made by the FTC in the agency’s complaint against OMICS Group Inc. It’s also worth repeating that not all open access journals sacrifice competent peer review, sound editorial guidance and other accepted business practices in return for increased profits.

Ho emphasized that publication in an open access source does not automatically mean that the research is bad. Much of it, in fact, is sound. Some open access publishers take shortcuts with the review and publishing procedures, however, and that possibility makes stricter scrutiny more important for authors, researchers and veterinary practitioners.

To learn more about predatory journals and to help identify reliable open access publications, Ho suggested these websites: the Directory of Open Access Journals (https://doaj.org) and the “Think. Check. Submit” initiative (https://thinkchecksubmit. org/check).