As a radiologist and assistant professor of Clinical Large Animal Diagnostic Imaging at Penn Vet, Elizabeth Acutt, BVSc, MS, DACVR, works on a lot of referrals that come into the hospital. In this case, a 16-year-old Quarter Horse gelding presented with a Grade 3 out of 5 right-hind lameness. The referring veterinarian had worked the patient up with local analgesia, blocking the lameness out to a subtarsal block.

Acutt noted that while veterinarians rely on blocks to localize lameness, more published research is showing they might not be as accurate as hoped. “It’s important for us to keep in mind that when we block an area, we might be blocking other things as well,” she said.

The veterinarian in this case decided to do an ultrasound of the horse’s proximal suspensory ligament to see if there was evidence of injury to that structure. They noticed enlargement of the ligament as well as some fiber heterogeneity in that region.

“So at this point, we kind of have a nice story, right?” said Acutt. “The horse blocks to this region, and we have some abnormalities on our ultrasound. They went ahead and rested the horse for 30 days since, in general, soft tissue injuries tend to respond well to a decreased exercise regimen.”

Unfortunately, the horse’s lameness did not improve with rest and rehab. “Again, this is kind of where we go back to our knowledge of the blocking and think, ‘OK, well, is there something else going on here that we might be missing?’” she said. “Knowing that this blocking pattern might also reach other sources of lameness in this region, the vet referred the horse in for a CT of its proximal metatarsus and its tarsus region to kind of give a global assessment.”

This is when Acutt became involved in the case. On CT, she found that the horse had moderate to severe osteoarthritis of its tarsometatarsal joint and lysis and bone loss within that joint space.

“Now we have both proximal suspensory abnormalities on ultrasound and tarsometatarsal joint abnormalities on CT,” she explained. “So the next question that we’re kind of asking ourselves is which of these is the primary contributor toward the horse’s lameness? That can be a really difficult puzzle to figure out.”

To save the horse’s owner time trying to determine which of the horse’s injuries was the primary issue and to get him back to work faster, Acutt recommended a positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

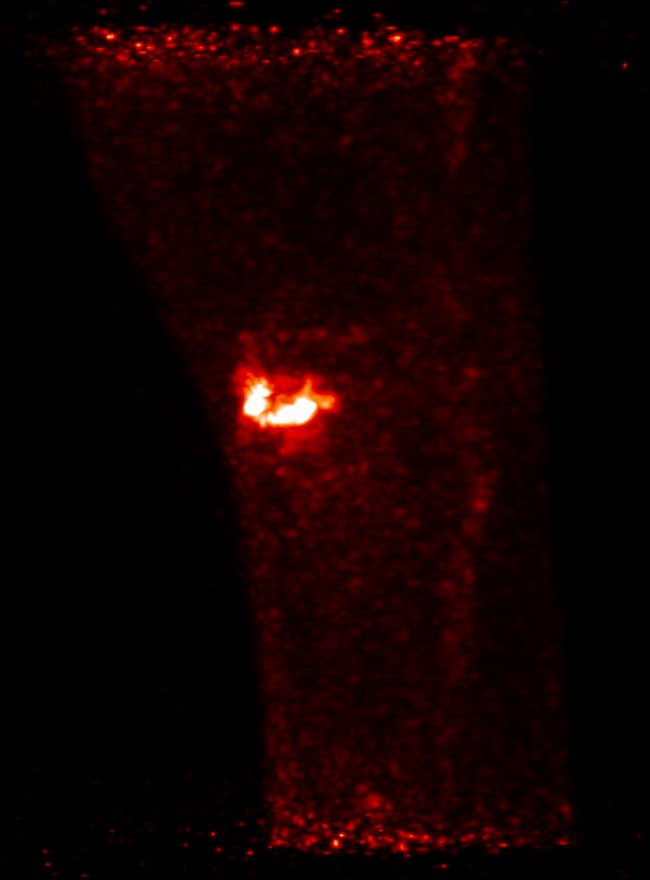

“Basically, PET uses radioactive tracers to determine how active certain lesions are,” she explained. “We can use this modality here because we have these multiple lesions present—one in the bone, one in the soft tissue—and we’re trying to decide which one is more clinically relevant.”

Listen to the episode in its entirety to learn more about PET technology and what Acutt found on this horse’s scan.

About Dr. Elizabeth Acutt

Elizabeth Acutt, BVSc, MS, DACVR, obtained her veterinary degree from the University of Bristol, United Kingdom. She then traveled to the University of California, Davis to undergo additional training in her areas of interest, which are equine orthopedics and sports medicine. She was the first person to complete a residency specifically in equine diagnostic imaging, based at Colorado State University and became a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Radiologists (EDI) in 2022. She remained at CSU following her residency in the role of Senior Fellow in Veterinary Diagnostic Imaging. Dr. Acutt’s clinical and research interests focus on comparative imaging in the equine athlete. She joined the faculty at Penn Vet in May 2023.

Related Reading

- Choosing the Right CT Technology for Equine Vets: Fan-Beam vs. Cone-Beam

- Monitoring Racehorse Injuries With PET: Peak Training Best Time

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET): Not Just for Racehorses

Stay in the know! Sign up for EquiManagement’s FREE weekly newsletters to get the latest equine research, disease alerts, and vet practice updates delivered straight to your inbox.