Advances in imaging and diagnostics are leading to earlier and more frequent diagnosis of DJD in horses. This is heightening awareness that degenerative joint disease (DJD) can be a problem for horses of all ages. Awareness is a win for those horses.

“I think we’re surprised how many times a relatively normal-looking joint on radiographs will have fairly substantial changes on MRI or CT,” said Christopher E. Kawcak, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, ACVS founding fellow/MIS and director of Equine Clinical Services at Colorado State University (CSU). For veterinarians who don’t use a lot of CT and MRI, he thinks “we are likely under-diagnosing DJD.”

Improving Diagnostics

There was a consensus among veterinarians participating in a 2020 roundtable on DJD sponsored by American Regent Animal Health that more DJD will be found as equine diagnostics become better, easier and more available—particularly with the advent of the standing CT scanner.

They also agreed that owners and trainers have long recognized that maintaining joint function and reducing joint pain is critical to performance. But, without a thorough evaluation and the availability of more advanced diagnostics, this disease has gone largely “under-diagnosed and over-treated.”

Gary White, DVM, owner of Sallisaw Equine Clinic in Oklahoma, explained it like this: “People will go to a veterinarian and get eight or 10 joints injected at one trip. I question whether that horse received a good examination and a good diagnosis.”

Kelly Tisher, DVM, managing partner at Littleton Equine Medical Center in Colorado, agreed with White. However, he said that in his practice, he feels that clients and trainers have become better over the last decade or so at valuing the veterinarian’s exam to obtain a proper diagnosis before beginning treatment.

Rick Mitchell, DVM, MRCVS, DACVSMR, an owner of Fairfield Equine Associates and a founding member of ISELP, said he doesn’t think veterinarians are over-diagnosing. But, he does think there’s a tendency to over-treat. “I think there is a trend from trainers and owners to [tell us to] ‘do whatever you can to fix the horse to make it go. We’ve got to go to a horse show next week.’ We have to back up and try to practice quality medicine.”

Start With a Thorough Exam

Quality veterinary medicine includes a thorough physical exam along with diagnostics.

Zach Loppnow, DVM, formerly an associate veterinarian at Anoka Equine Veterinary Services in Minnesota and currently a first-year equine surgery resident at Steinbeck Country Equine Clinics in California, said, “Personally, I work really hard to not just go off of the radiographs or the imaging, but to correlate that to the horse in front of me. And maybe that’s where you fall into the trap of under-diagnosing the subclinical arthritic horses.

“I had a horse that had pastern arthritis, [which] was what we were treating,” Loppnow said. “We used regenerative therapies in that joint. The horse is doing great. But, we did some survey radiographs of the carpi on that horse because there’s a little bit of abnormal swelling. There was some osteophyte proliferation in those joints—but the horse blocked out to the pastern joint. So, if clinically I’m treating what’s causing the lameness, am I missing some of the subclinical stuff that may be causing a problem down the road? Am I missing that opportunity to catch it early?”

CT and MRI to Diagnose DJD in Horses

The use of CT and MRI improves the chance of diagnosing DJD. Kawcak said that veterinarians who don’t use a lot of CT and MRI are likely under-diagnosing DJD. “Especially when you start looking at subchondral lesions, things that can progress post-traumatic OA. And again, similar to the racehorse, I think we’re surprised about how many times a relatively normal-looking joint on radiographs will have fairly substantial changes on MRI or CT. But, at the same time, what does it mean to the horse? Sometimes you see fairly dramatic changes, and it doesn’t mean much to him.”

Kawcak thinks that in the next year or two, with new imaging technologies more readily available, vets will be “a little bit overwhelmed” with the changes that occur in the back and pelvis that “right now are a little bit frustrating to characterize objectively.”

Treating on Assumption vs. Diagnosis

Even more frustrating can be encountering a horse that has been treated based on assumption instead of a thorough diagnosis. As a result, Robin Dabareiner, DVM, PhD, DACVS, who worked at Texas A&M for 23 years before joining Waller Equine Hospital in Texas, said she gets a lot of horses for second opinions.

“The typical barrel horse isn’t performing; it’s not taking the right barrel,” she described. “And when I see it, what’s been done is hocks and stifles and fetlocks in the rear have all been injected. The horse may have been to one or two veterinarians. It has not had a thorough exam—meaning a diagnostic nerve block to locate the lameness. I would block the horse out, and it ends up with a high suspensory or a soft tissue injury.”

Poor Performance in Horses with DJD

Dabareiner noted that many horses whose owners thought they had poor performance issues actually ended up having lameness issues once diagnostics were undertaken. “I agree with [this group] that I’m seeing way too many horses over-treated versus localizing the problem,” she said. She cites research she published during her tenure at Texas A&M.

Three of the studies in which Dabareiner was involved focused on Western performance horses (cutting, team roping and barrel racing competitors). They were published in JAVMA:

- Lameness and poor performance in horses used for team roping: 118 cases (2000–2003)1

- Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance among horses used for barrel racing: 118 cases (2000–2003)2

- Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance in cutting horses: 200 cases (2007– 2015)3

Veterinarian’s Professional Insight for Diagnosing DJD in Horses

Even with improved diagnostics, a veterinarian’s professional insight remains critical. With more widespread availability of standing CT in the next two or three years, Kent Allen, DVM, owner of Virginia Equine Imaging and a founder of the International Society of Equine Locomotor Pathology (ISELP), thinks that veterinarians will see more DJD. However, he continued, some of those findings will be relevant and some will be irrelevant. He said that over the years in his career, as diagnostics have improved, it has taken experience to be able to say, “That is a change, but that’s just a modeling change and that’s not a big deal.” He added that putting those findings in perspective is important.

Kyla Ortved, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, the Jacques Jenny Endowed Term Chair of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center, added, “I think for the most part, we have really good tools in our toolbox to diagnose horses currently, and we likely will be developing more tools. But the horses need to be seen [by veterinarians] in order for us to use the tools on them.”

The Owner’s Role in Recognizing DJD

Preventing cartilage and joint problems rather than treating them was a point of discussion among the veterinarians. Mitchell said he asks clients: “What’s it going to cost you to replace this horse?” Then he tells them: “Compare that expense to what it would cost to maintain this horse properly.”

He added that his “pitch” to horse owners is that “prevention is way easier than treatment” when it comes to DJD.

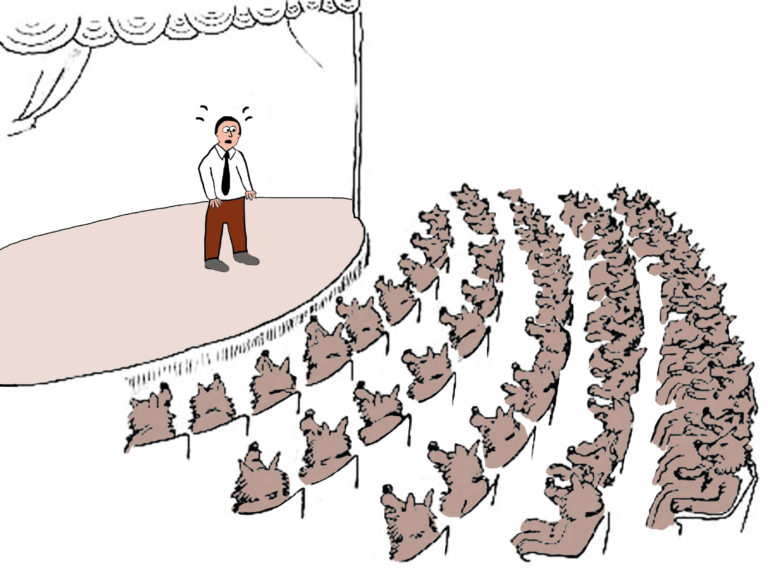

Tisher said one problem in addressing lameness issues with horse owners is that “oftentimes they reach out to about everyone else before their veterinarian in response to trying to fix some of the issues—whether they’re large or small, whether they’re performance issues or something that’s quite substantial. The list of professionals or ‘supposed professionals’ that get to weigh in before we get to weigh in is kind of long sometimes.

“I’m not saying that the rest of those professionals don’t add to it,” he continued. “It’s the order sometimes that frustrates me, and the opportunity to intervene before there’s been other things that have been done.” As a result, owners often have spent a tremendous amount of money before veterinarians get the opportunity to examine the horse.

Dabareiner added, “I’m sure we all have the owner that, first thing they do is go to a chiropractor. Or they listen to their friends, or they go to the internet.”

Placing Higher Value on Veterinary Exam

Educating clients and involving them in their horses’ care can help them place higher value on the veterinary exam so it takes place sooner.

White sees a couple of types of owners: “We have some that, if you listen to them, they can really help you with your diagnosis,” he said. “Others don’t have a clue, and you pretty much have to discard what they say. But it helps if you understand the discipline and you know what questions to ask.”

He hopes that going forward, the second group of horse owners—“if you make them think about what the horse is doing”—will pay more attention to what their horses are telling them.

Being Proactive in Addressing DJD in Horses

Allen hopes proactive education will reduce the number of owners who bring in an obviously lame horse. He said that when those owners ask him “What can I do?” to help their horses stay sound, he recommends that the average performance horse have a twice-a-year soundness exam with podiatry films used to advise the horse’s farrier.

“We can look at the horse, do a complete physical soundness examination … palpate the back, palpate the SI [sacroiliac joint], block things that they need blocked,” said Allen.

He tells owners: “Bringing the horse in twice a year for a lameness exam is what you can do that will undoubtedly prolong this horse’s athletic life. We can detect arthritis early and come up with a rational plan.”

Kawcak agreed, adding that even with some very successful trainers and riders, “you look at the horse and wonder how it got to this point.” And he said there are others who think “a training-related issue has got to be a physical ailment of some sort.”

How to Ask the Right Questions as a Veterinarian

He encourages veterinarians to ask a client the right questions to get an understanding for the significance of the horse’s problem. “I think people are starting to maybe understand where they struggle in managing their horses. I think in those cases [they are] reaching out more,” said Kawcak.

The difficulty of positioning yourself as a client’s first resource is a frustration Loppnow experienced firsthand. “I’ve got to say it’s making me feel a lot better that it’s not just me that the clients are avoiding and going to chiropractors and everybody else first,” Loppnow said. “The fact that it sometimes seems like the veterinarian is the last resort rather than the first opinion is something that’s really challenging to deal with. And I think I often find myself spending about half my time proving what it isn’t before I can actually prove what it is, because they’ve gotten so many other opinions from other people.

“I think everybody has a role in keeping a horse sound and performing well—chiropractors, acupuncturists, massage therapists, whatever alternative therapy you want to use—but you have to figure out what the problem is first, and then bring those other parts on board,” Loppnow added.

Role of the Client in Managing DJD in Horses

The team approach to DJD includes the client. That’s why Loppnow has a consistent message for owners: “You know this horse better than anybody else … in terms of how it feels, how it moves, what it’s doing—and I need that perspective from you. So, take note of when it’s not doing what you normally expect it to do. Take note of how that’s changed, what it’s doing differently. The more time-based information you can give me on when it’s doing things [and] what it’s doing, the better I can diagnose what may be going on.”

Mitchell referenced a paper by Sue Dyson, MA, VetMB, PhD, DEO, FRCVS, in Europe on a group of 57 horses that were presumed sound by trainers and owners. Only 14 of the 57 horses were determined to be sound after veterinary examination.4

Mitchell thinks veterinarians fall short in taking time to talk and listen to owners. However, massage therapists, chiropractors and others do take time to have conversations. “I think if we spent a little bit more time, we can gain information that will help us do a better examination,” he said.

Importance of Educating Owners

Owners and trainers are familiar with many different therapeutic options for management of joint problems. However, they are poorly equipped to evaluate the best practices or to appropriately tailor treatments to an individual horse. Ortved thinks that providing targeted education to help clients understand what veterinarians can do is important. Not to mention actually teaching them what DJD is.

“I think that’s sometimes where they fall into the trap of this whole idea of maintenance injections. They have this understanding or perception that if they maintain the joints with staged or serial injections every three, six, nine, whatever months they do, then they’re preventing anything from occurring and that’s the best way to approach it,” said Ortved. “They don’t necessarily have a good understanding of what arthritis is and what that means for a specific joint. It’s not a widespread problem that happens in every single joint of the body that’s possibly injectable.

Knowledge Sharing Between Vets and Owners

“So, I guess the piece that seems to be missing is that knowledge sharing between our profession and horse owners, trainers and other professions,” concluded Ortved.

Loppnow wrapped it up by stating, “I think it’s all about controlling the conversation [with owners]. It’s making sure that we’re setting ourselves up to be the first resource, not the third or fourth resource, with each horse.”

Ways to do that center around effective communication, whether in person, via phone or text, or with email.

In the veterinary field, many studies have supported the essential nature of communication skills in achieving success in practice. The four key elements of good communication are non-verbal communication (i.e., recognizing your own and the client’s body language), open-ended inquiry (asking questions that require more than a yes or no answer, such as “Tell me…” “What…” “How…” or “Describe for me…”), reflective listening (“What I’m hearing you say is that JoJo has been refusing jumps and feels ‘off ’ on his right foreleg”) and empathy (seeing the situation through the client’s eyes, such as “I know you really wanted to show JoJo this weekend, but with this lameness I think you will want to give him some time off so we can get to the bottom of this problem”).

References

1. Dabareiner, R.M.; Cohen, N.D.; Carter, K.; Nunn, S.; Moyer, W. Lameness and poor performance in horses used for team roping: 118 cases (2000-2003). JAVMA 2005; 226: 1694-1699.

2. Dabareiner, R.M.; Cohen, N.D.; Carter, K.; Nunn, S.; Moyer, W. Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance among horses used for barrel racing: 118 cases (2000-2003). JAVMA 2005; 227: 1646-1650.

3. Swor, T.M.; Dabareiner, R.M.; Honnas, C.M.; Cohen, N.D.; Black, J.B. Musculoskeletal problems associated with lameness and poor performance in cutting horses: 200 cases (2007-2015). JAVMA 2019; 254: 619-625.

4. Dyson, S.; Greve, L. Subjective Gait Assessment of 57 Sports Horses in Normal Work: A Comparison of the Response to Flexion Tests, Movement in Hand, on the Lunge, and Ridden. J Equine Vet Sci 2016; 38: 1-7.