The dog days of summer are here, and that means arbovirus season is in full swing. Peak arbovirus season can span from July through October.

Equine encephalitis viruses, including Eastern, Western, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis (EEE, WEE, VEE) and West Nile virus (WNV), are spread by infected mosquitos and can cause severe encephalitis in equids and humans. These viruses are widespread in birds and rodents, making them reservoirs for disease.

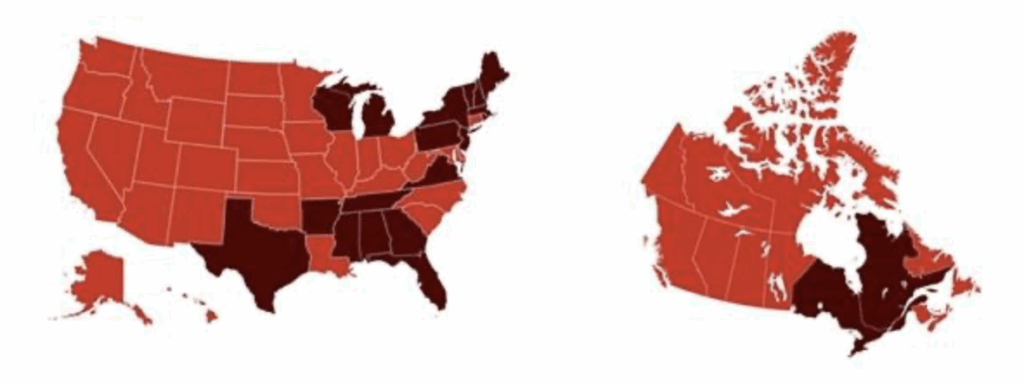

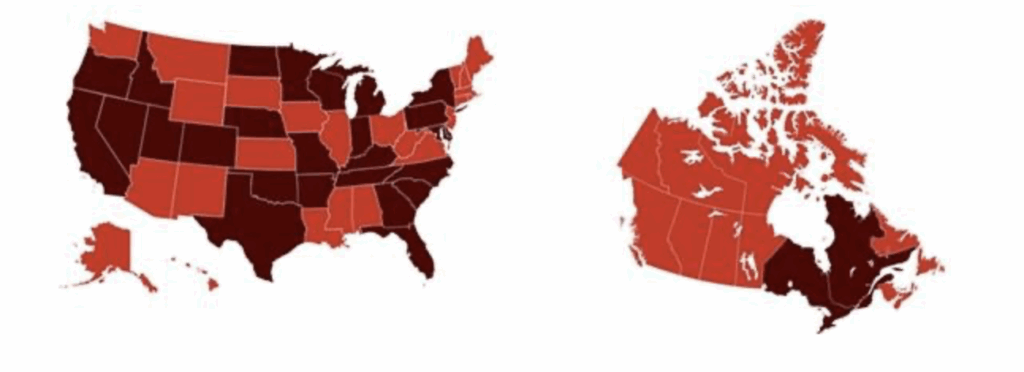

Last year, the Equine Disease Communication Center received submissions for 126 EEE cases and 153 WNV cases throughout North America. Of those cases, 96 horses died from EEE and 39 died from WNV. (See figures 1 and 2 for location of EEE and WNV cases submitted to the EDCC by state and province in 2024. Note: not all states or provinces submit infectious disease cases to the EDCC).

Vaccination

Unvaccinated horses are particularly susceptible to arborviruses. Keeping horses up to date on vaccinations is the most effective way to prevent life-threatening infection.

The initial vaccination is followed with a booster four to six weeks later. Yearly revaccination is recommended at minimum, and more frequent boosters (i.e., twice yearly) might be necessary in areas with year-round mosquito season. Recommendations from the American Association of Equine Practitioners are available HERE.

With no disease-specific treatment options available for arboviruses, prevention is key to avoid serious illness or death. Vaccination is the most effective way to protect horses against these viruses. Mosquito control can also help prevent disease exposure.

Vaccinating horses against EEE and WNV reduces the risk of horses contracting a severe infection after being bitten by mosquitos. Vaccination lowers the risk of death in horses exposed to EEE and WNV. In the event that a vaccinated horse becomes infected with EEE or WNV, the symptoms tend to be less severe with a quicker recovery time compared to unvaccinated horses. Preventing EEE or WNV is more cost-effective than treating a horse with encephalitis, which might require intensive veterinary care or even hospitalization, alongside costly supportive treatments.

Another way to lower infection risk is to practice good mosquito management on horse properties by providing shelter with fans at dawn and dusk, eliminating standing water, and using insect repellents.

Eastern Equine Encephalitis

EEE, also known as the sleeping sickness, is a viral disease that causes inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. There is no cure for EEE, but supportive care might help infected horses displaying clinical signs. The virus can only be transmitted to a horse via an insect vector; infected horses cannot transmit the disease to other horses. The incubation period for EEE after a horse is bitten by a mosquito is five to 14 days.

Clinical signs of EEE include depression and anorexia, initially without a fever when first infected. Other clinical signs include moderate to high fever, lack of appetite, and lethargy/drowsiness. The onset of the neurologic disease is frequently sudden and progressive, including periods of hyperexcitability, apprehension, and/or drowsiness; fine tremors and fasciculations of the face and neck muscles; cranial nerve paralysis; head tilt; droopy lip; weakness; complete paralysis of one or more limbs; circling; convulsions; recumbency; and death. Owners might initially confuse clinical signs with colic pain. Horses infected with EEE rarely survive. The mortality rate is 75-95%, and death usually occurs within two to three days of onset of clinical signs.

West Nile Virus

Like EEE, WNV causes inflammation of the nervous system for which there is no cure. Horses displaying clinical signs can benefit from supportive care. Although some infected horses never show clinical signs of disease, clinical disease develops in up to 39% of infected horses. Horses that survive usually make a full recovery, though some horses have lingering or recurrent neurologic deficits. Horses that become recumbent and are unable to rise have a poorer prognosis than those that remain standing. The approximate mortality rate is up to 40%.

Clinical signs include fever, lack of appetite, lethargy, and neurologic signs. Hallmark clinical signs include fine muscle fasciculations of the muzzle and face and episodes of somnolence. Other clinical signs include periods of hyperexcitability, apprehension, cranial nerve paralysis, head tilt, droopy lip, muzzle deviation, complete paralysis of one or more limbs, recumbency, and death. Horse owners might mistake clinical signs for colic pain.

The incubation period for WNV is seven to 10 days. Like EEE, WNV-infected horses are not contagious and cannot transmit the disease.

The following map shows the regions in North America affected by EEE and WNV in 2024. With the amount of rain across the country this year, more cases can be expected in unvaccinated horses. Veterinarians should educate their clients on the recommended guidelines for EEE and WNV vaccination.

The EDCC is an industry-driven information center that works to protect horses and the horse industry from the threat of infectious diseases in North America. The center is designed to seek and report real-time information about diseases similar to how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Center (CDC) alerts the human population about diseases in people. The EDCC is based in Lexington, Kentucky, at the American Association of Equine Practitioners headquarters, with a website hosted by US Equestrian. The EDCC is funded entirely through the generosity of organizations, industry stakeholders, and horse owners. To learn more, visit www.equinediseasecc.org.

Related Reading

- A Refresher on Protecting Horses Against Arboviruses

- The Future of Equine Infectious Diseases in a Changing Climate

- Researchers Identify Potential New Transmission Method for West Nile Virus

Stay in the know! Sign up for EquiManagement’s FREE weekly newsletters to get the latest equine research, disease alerts, and vet practice updates delivered straight to your inbox.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #18379](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wp-s3-equimanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/30140703/EDCC-Unbranded-15-scaled-1-768x511.jpeg)

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #18808](https://s3.amazonaws.com/wp-s3-equimanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/06141153/EDCC-Unbranded-17-scaled-1-768x512.jpg)