Fungal keratitis is an infection of the clear outer surface of the eye (the cornea) caused by a fungus; the most common culprits are Aspergillus sp. and Fusarium sp. If not treated quickly and aggressively, fungal keratitis can lead to loss of vision or even loss of the eye itself. The incidence of fungal keratitis in horses is much higher than in other domestic species. It is suspected that this occurs because horses have fungi living normally on the surface of the eye and the environment horses live in exposes them to fungi on a more frequent basis. Without a pre-existing wound or ulcer, the presence of fungi is not normally a problem for the horse. However, when a corneal ulcer is present, organisms normally on the anterior surface of the eye can result in an infection. Infection of the cornea can be devastating due to the often aggressive nature of fungi. Fungi release collagenolytics that break down the cornea and antiangiogenic factors that stop the growth of healing blood vessels into the cornea.

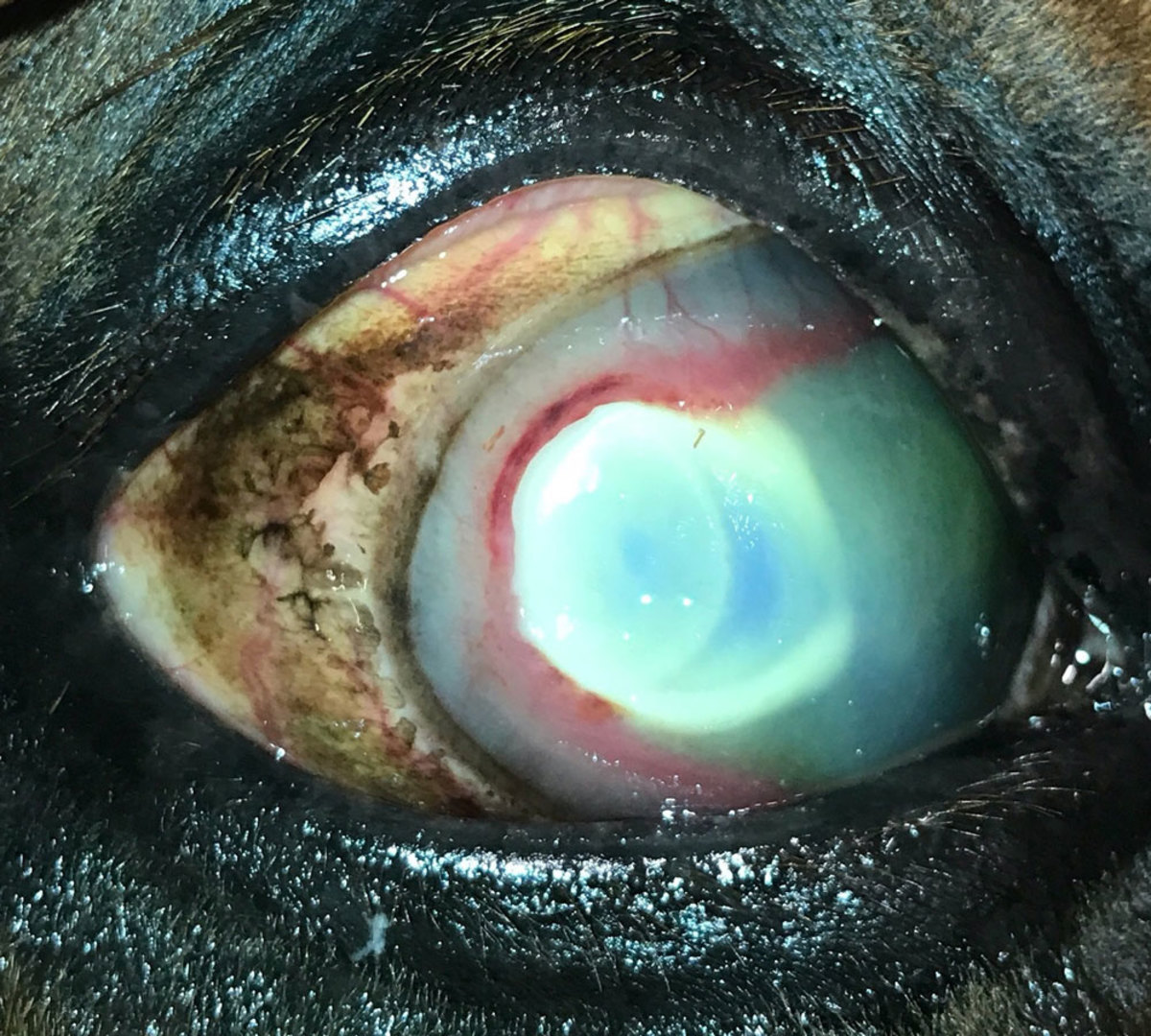

Fungal keratitis can result in two types of lesions, an ulcer or abscess. A fungal ulcer is usually whitish-yellow and irregular in shape; it is often surrounded by a groove (Figure 1).

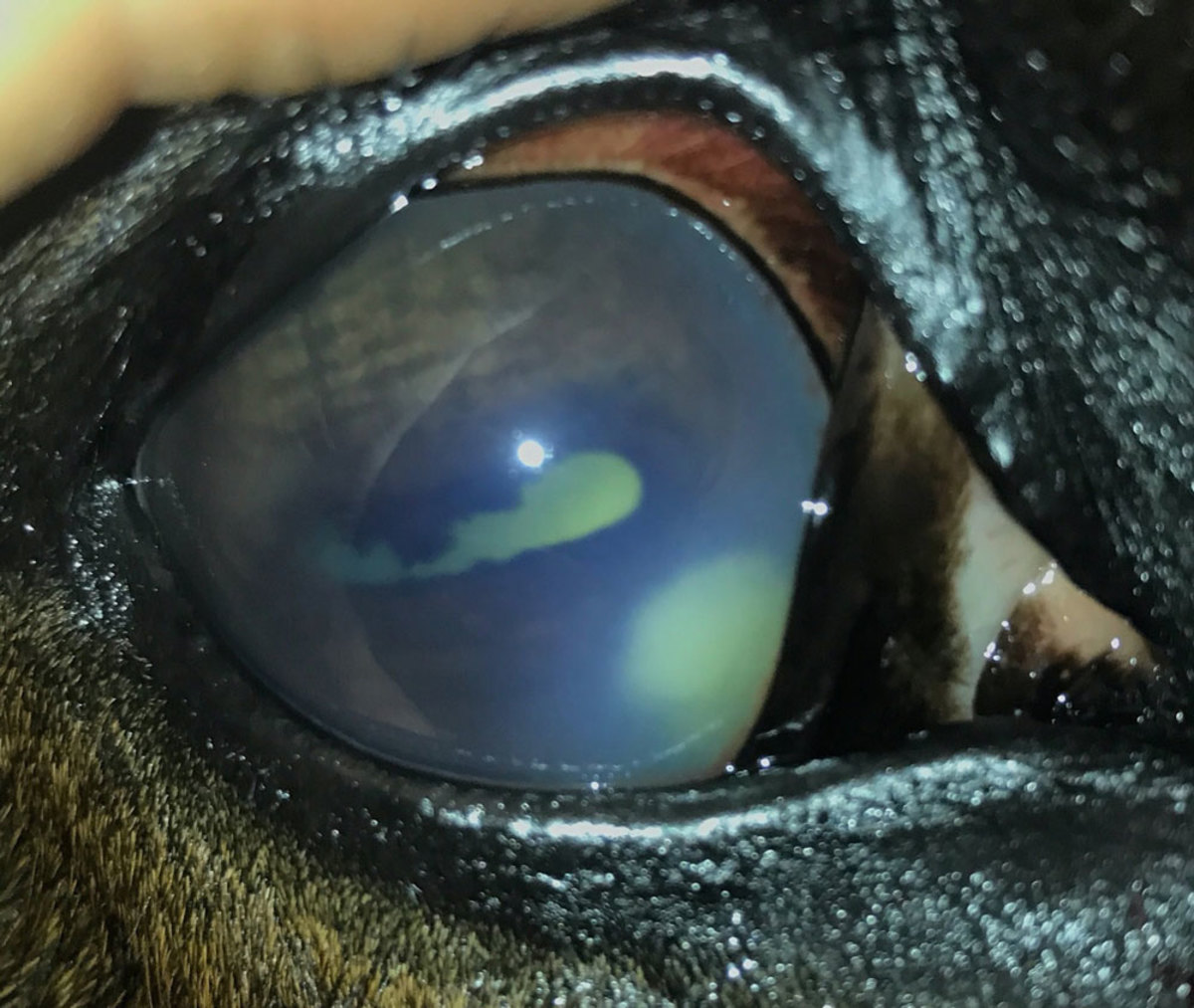

A stromal abscess generally starts as a corneal ulcer whose superficial layer heals and essentially traps the fungus within the cornea making it more difficult to treat. Affected eyes present with a smooth, yellow haze (Figure 2).

Initial treatment for a corneal ulcer usually consists of a topical antibacterial medication to prevent more commonly encountered bacterial infections. A simple corneal ulcer should heal within 5-7 days. If it does not, it becomes a complicated ulcer.

Geographic location of a horse alone might influence a veterinarian’s concern about a fungal infection. In the United States, it has been shown that Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern states have a high prevalence of keratitis, whereas the problem is much less common in the western states.

There are many reasons for the development of a complicated ulcer. One of the tests a veterinarian can do to determine why an ulcer is not healing is a corneal scraping for cytology. If the ulcer is infected, a specific inflammatory cell called a neutrophil is present. In some cases, cytology can also help determine if the infection is bacterial or fungal.

If fungal keratitis is suspected, an antifungal agent should be included in the treatment plan. The choice of an antifungal agent is based on the antimicrobial sensitivity of fungi in the area and level of the veterinarian’s suspicion of the presence of a fungal infection. Many general practitioners will not have a topical antifungal agent on their trucks. In such instances, silver sulfadiazine (a common wound cream) or miconazole (typically available at your local pharmacy) can be used until a more appropriate antifungal medication can be ordered.

In the case of any ocular infection, it is highly important that whatever medication(s) are used, are approved for application to the eye. Where treatment proves difficult, placement of a subpalpebral lavage catheter can be considered to facilitate successful treatment.

In cases of severe fungal disease, referral to an ophthalmologist should be discussed with the client to determine if surgical intervention is required. Even in severe cases, surgical intervention can be successful in preserving vision.

For more information contact author Nikki Scherrer, DVM, DACVO, at scherrer@vet.upenn.edu or call 317-691-7339 to reach her at the New Bolton Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Kennett Square.

This article was reprinted with permission from the Equine Disease Quarterly, Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky.