There is no question that a professional veterinary education is comprehensive, preparing future practitioners for many situations. Yet not every possibility can be presented to students in a standard curriculum.

One disconnect that is rarely touched upon, except at a few universities, concerns the logistics for equine rescue and disaster response. It is not uncommon for equine veterinarians to encounter emergency situations for the first time with the expectation by others that the veterinarian knows how to resolve crises. Without preparation, such an event can be daunting for even the most capable practitioner.

To remedy this kind of educational gap, an excellent program was organized by Colorado State University veterinary students from the Student Chapter of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (SCAAEP). They invited John Madigan, DVM, MS, DACVIM, and Jim Green to present at SCAAEP’s annual weekend lecture and wet lab for interested first responders.

Madigan is world-renowned for his advances in equine rescue operations and is the founder of the UC Davis Veterinary Equine Response Team (VERT). Green hails from the United Kingdom and is an animal rescue specialist of the Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service, as well as serving as director of the British Animal Rescue and Trauma Care Association (BARTA). He said that he and his team manage at least one large animal rescue operation each week. Currently Green and Madigan are working together at UC Davis with a focus on emergency preparedness and the integration of vets and first responders.

The kinds of equine incidents requiring rescue are as numerous as one’s imagination. They include trailer accidents; horses falling into ravines, holes, wells or through ice; horses stuck in bogs or cattle guards; loose animals; downed or recumbent horses; and fires and floods that make evacuations and triage necessary.

“While these situations may not occur with great frequency, they are associated with high risk and danger to personnel working to extract a horse,” said Madigan.

Because of that, it is important for veterinarians to work together as a cohesive unit with first responders and other agencies. An equine veterinarian’s role encompasses a number of important functions, ranging from tactical planning, chemical restraint and pain control to triage, casualty management and the potential necessity of euthanasia. He noted that these tasks are an expansion of services and functions that most equine practitioners perform daily.

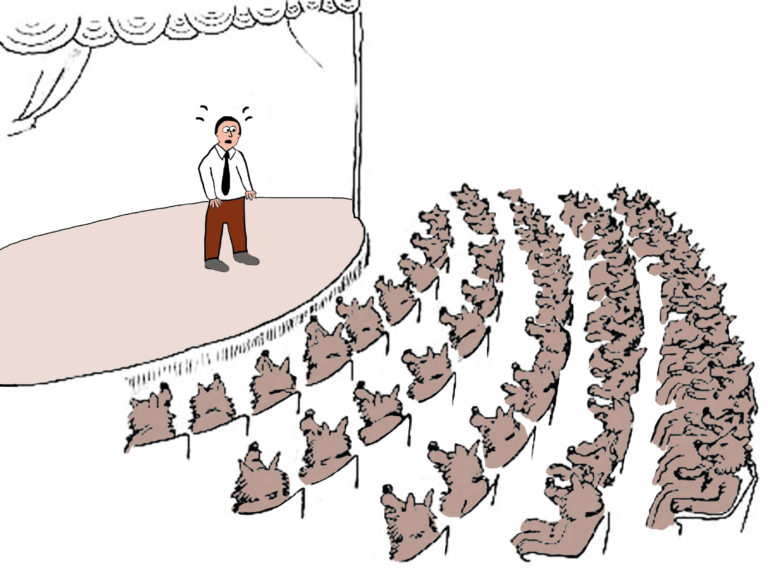

As Green pointed out, “Surveys have shown that 83% of people say they will risk their lives for their animals.” With that in mind, it is likely that a lay person will intervene and put himself/herself in harm’s way before professional help arrives at the scene. When animals are in distress, Madigan said, “People behave irrationally. A veterinarian’s skills help keep responders and horse owners safe, while also improving the viability of the casualty animal.”

The Incident Command System

Both of the experienced rescue experts emphasized that it is critical to work within an incident command structure (ICS) when faced with a rescue or emergency response situation. ICS is an operational protocol that revolves around a hierarchy of people, tiered with different functions and positions, all controlled by a team leader with recognized authority.

Firefighters and other first responders already have this structure in place; these agencies commonly respond to calls for help. Communication with all members of the rescue group is key to an effective operation. A veterinarian arriving on the scene should check in with the incident commander (IC) first. Just as there are designated tasks, specific jobs and positions within a surgical operating room, the same concept applies to working with a rescue and emergency response team.

Safety is the top priority. Besides working under the direction of an incident commander, Madigan urged veterinarians to use personal protection equipment (PPE) such as helmets and safety vests. Not only is this practical, but showing up to the site already garbed in PPE enables quick integration into the response team—first responders then have more confidence that the veterinarian is knowledgeable about what could happen at the scene.

Madigan explained that having the veterinarian work within an incident command system reduces the obligations of the veterinarian, so that he or she is empowered to be most effective at carrying out the critical role of medical doctor. Green remarked, “In these stressful situations, there is a need for compassion without emotion.” First responders and veterinarians are good at this.

Madigan advised that veterinarians not take on more responsibilities during an operation than they can cope with. They should also be prepared to be flexible, he said, stressing that they should “… take a pause to increase observation of the patient, and to get an overview of what needs to be done before diving in to act. Get some history on the situation, step back and assess, and then reassess.”

First and foremost is the need to stabilize the horse. This might mean taking time to administer IV fluids (20 ml/kg), and once the horse’s heart rate slows and mucous membranes look okay, then it can be moved. Moving the horse before it is stabilized could result in significant compromise to its survival.

Evacuation Principles

Equine veterinarians can also be effective liaisons with barn managers/owners and horse owners, teaching them about evacuation plans and logistics in advance of an event such as a fire or flood. (Two helpful UC Davis resources can be found at vetmed.ucdavis.edu. Search for Equine Emergency Preparedness poster and search for Horse Report Fall 2014.) Madigan said that there are two choices regarding evacuation:

1. Evacuate early, which is the preferred method. “Even if a shelter location is not yet identified, get the horses out of harm’s way,” he said.

2. Shelter in place by removing the horses from structures and providing them with long-term feed and water. Madigan urged that the horses be locked up or tied; otherwise, they will return to their known “safe haven,” which might be threatened or already on fire or flooded. In addition, loose horses are a hazard to people, traffic and themselves. Horses shouldn’t be allowed to run free unless there is an immediate danger to health and life. In those cases, personnel should be notified that horses are loose. Ideally, horses can be freed with a halter in place to facilitate catching them later.

Effective evacuation relies on the experience of knowledgeable teams. If horse trailers aren’t available or are unable to access the area, then Madigan’s advice is to lead or ride the horses out.

Another important point discussed is that some states have “fence-out” regulations, meaning that property owners are required to fence animals (not owned by them) out of their property. The result is that only first responders are allowed to open gates and cut fences in the event of a crisis, whereas well-meaning residents and volunteers are not.

Local first responders at the seminar said that the Disaster Animal Response Team that is led by the Larimer County Humane Society in Fort Collins, Colorado, works in conjunction with the Larimer County Horse Association. They conduct frequent training sessions, such as having volunteers and first responders practice loading horses into unfamiliar trailers. These sessions establish a relationship with the incident commander.

There is always a concern about compensation for the financial costs of treating injured animals at veterinary hospitals, particularly when there is no identification that connects a horse with its owner. It might be necessary to fundraise in order to provide payment for injured animals treated by a veterinary practitioner.

Recumbent Horses

When faced with a “down”/recumbent horse that cannot rise, Madigan stressed that only those people who are optimistic about getting the horse back on its feet should be encouraged to stay and help. Those kinds of situations need positive approaches that seek every possible means of aiding the horse. He also noted the importance of debriefing sessions that welcome communication from everyone invested in the operation. This provides an opportunity to discuss what could be done differently and allows everyone to have a say, which might help with the decision-making process.

Another important point mentioned is related to infectious disease possibilities. When examining a recumbent horse, it is a good idea to look for signs of rabies or equine herpesvirus type 1 infection. Equine herpesvirus myelitis (EHM) can present as an acute neurologic onset, with an owner noting that the horse seemed okay other than a recent history of fever and nasal discharge before suddenly collapsing. An EHM horse might have clinical signs of vasculitis— such as injected gums or limb edema—and/or there might be evidence of urinary incontinence or bladder overflow. Before a horse is moved into a veterinary hospital or a barn housing other horses, infectious and zoonotic disease possibilities need to be considered and biosecurity measures implemented.

Once a trapped or recumbent horse is assessed, then equipment can be used to sling, lift and move it. Two devices are available to help with this process: a large-animal lift and the Anderson Sling support device. This equipment can be used to helicopter a horse to a safe place for further observation and treatment. It can also help support a horse that has difficulty standing for weeks or months.

Emergency Response Educational Opportunities

Advanced training in large animal rescue operations is available through many sources. Some examples are listed below, in no particular order:

• UC Davis Veterinary Medicine: vetmed. ucdavis.edu/ceh/disaster_preparedness/ training_courses.cfm

• British Animal Rescue and Trauma Care Association: bartacic.org

• Emergency Equine Response Unit: eerular.org

• Code 3 Associates, in association with Colorado State University: code3associates.org

• Technical Large Animal Emergency Rescue: tlaer.org

• US Rider Equestrian Motor Plan: usrider.org

• Missouri Emergency Response Services: mersteam.org

• Large Animal Rescue Company based in California: largeanimalrescue.com

• J Woods Livestock Services in Canada: www.livestockhandling.net

• Large Animal Emergency Rescue Network, with worldwide resources: laern.org

• Animal Rescue Training in California: animalrescuetraining.com • Washington State Animal Response Team: washingtonsart.org

Other rescue training can be found on saveyourhorse.com/wholearn.htm. In addition, the following courses are available with a small animal or human focus:

• HASTPSC in Virginia, oriented toward small animals and equipment: hastpsc.com

• Ready Vet Emergency Response Plans, oriented mostly toward small animal: readyvet.com

• Rescue Tech International, geared to human rescue: rescuetechinternational.com

Take-Home Message

Equine rescue and emergency response can be a gratifying experience for a veterinarian. Practitioners can collaborate with local first responders to serve as a resource, while providing valuable expertise to horses in need and to the community.