General anesthesia has a mortality incidence of 0.12-2% in the general horse population. Post-anesthetic myopathy (PAM) occurs in 0.81-2% of horses, with a mortality rate of 16-20%. This concerning complication prompted clinicians at Michigan State University’s Valberg Neuromuscular Diagnostic Laboratory to take a closer look at a unique form of PAM. They described the clinical findings, outcomes, and muscle histopathology in warmblood horses that developed severe post-anesthetic rhabdomyolysis from 2016-2023.

What Is Post-Anesthetic Rhabdomyolysis?

Post-anesthetic rhabdomyolysis can develop as focal lesions of the triceps, extensor carpi radialis, or thigh muscles in horses in lateral recumbency during anesthesia. In dorsal recumbency, myositis develops in the epaxial and gluteal muscles. The authors described a more generalized PAM of many muscle areas: bilateral triceps, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, gluteal, hind limb adductors, pectoral, and epaxial muscles. Affected horses experience pain and distress; are unable to remain standing; and have muscle fasciculations, markedly firm muscles, myoglobinuria, and increased muscle enzyme activity.

Warmblood and draft horses, with their heavy body weight, are most prone to muscle ischemia and degeneration when placed in lateral recumbency under general anesthesia. The incidence of PAM in the general horse population is less than 2%, while draft horses have a high incidence of 7-8.3%. Certain disease predilections in warmbloods, such as type 2 polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM) and myofibrillar myopathy, might (but have not been proven to) increase their risk of PAM.

Post-Anesthetic Rhabdomyolysis in Warmbloods

In this retrospective review, researchers examined 2,962 medical records and muscle histopathologies performed at postmortem exam. The study identified PAM in 13 horses, including two Quarter Horses, two Clydesdales, one Belgian, one Belgian/warmblood cross, and seven warmbloods. Of the seven warmbloods, six were geldings and one was a mare. Complete medical records were available for six of the seven PAM warmblood cases.

The warmbloods ranged in weight from 1,212-1,550 pounds. They were under anesthesia for 60-230 minutes. Four horses had no health concerns at the time of surgery, one had a high score of systemic disease, and one did not have sufficient case details to form a value. There was no discernible difference between the use of inhalational or IV anesthetic agents. The researchers determined the following:

- All seven horses developed severe generalized PAM. Instead of the normal median of 37 +/- minutes to stand after anesthesia or 54 minutes +/- after colic surgery, the horses affected by PAM took 180-390 minutes to stand. All were stable under anesthesia.

- Serum CK and blood lactate were normal before surgery and markedly elevated after.

- Three horses could not stay upright in the recovery stall and were euthanized.

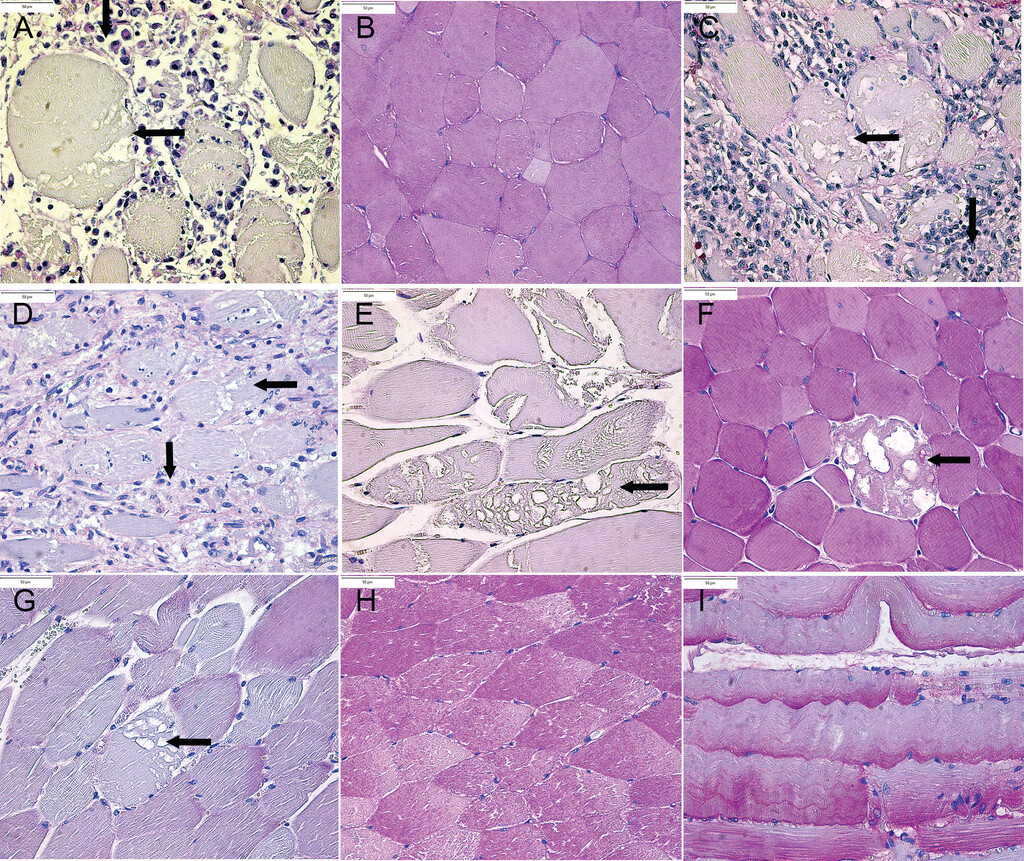

- Four horses “recovered,” but recurrence developed 5-11 days later, with histopathology showing severe myonecrosis and acute-on-chronic myodegeneration.

- Five of six horses had complete glycogen depletion and inflammatory cells of the muscle tissue as seen with PAS (periodic acid-Schiff) staining.

- Only one of the seven horses ultimately survived. That horse did not have abnormal histopathologic changes in the muscles at 15 days post-op.

Factors Contributing to PAM

The authors proposed that “development and recurrence of rhabdomyolysis as horses recover from anesthesia could reflect a disruption in muscle homeostasis created by hypoxia/reperfusion injury, a hypermetabolic event, and ongoing oxidative stress.” They did not consider body weight to be the sole contributing factor to PAM development in these warmbloods, whereas body weight does have a significant association with PAM in draft horses.

One factor associated with PAM is the lateral recumbent position, which appears to impact muscle perfusion of dependent muscles. Five of the seven horses in this study were positioned in dorsal recumbency, yet all developed generalized PAM. Long periods of anesthesia and accompanying hypoxemia and ischemia are also believed to be risk factors for PAM. However, while prolonged anesthesia correlates with poor recovery, it’s not a consistent finding with PAM.

Another factor that might contribute to PAM is a hypermetabolic event in recovery that results in high levels of lactate, likely consistent with profound anaerobic glycolysis. The authors noted: “Skeletal muscles, particularly fast twitch fibers, are exquisitely sensitive to ischemia reperfusion injury.” This correlates well with the study horses’ glycogen depletion and “inability to produce sufficient ATP for muscle function.” Genetic testing of one horse did not identify malignant hyperthermia (MH) that has a genetic basis in Quarter Horses. In the warmbloods, anaerobic glycolysis developed after anesthesia. The seven horses in this review did not have elevated body temperatures.

Oxidative stress is a possible sequela from reperfusion injury. This has the potential to heighten sensitivity to calcium activation and release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum with subsequent and delayed-onset rhabdomyolysis.

Six of the seven warmbloods had no evidence or history of a chronic myopathy like recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis (RER). The other horse had minimal glycogen depletion, but there was no data to suggest RER as a predisposition. Five of the horses were in regular exercise prior to surgery with no problems.

Therapies for PAM

Possible therapies for PAM include pain management, IV fluids, DMSO, vitamin E and coenzyme Q10 supplementation, and dantrolene, which impedes calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The authors stressed that it is important not to premedicate with dantrolene because it increases serum potassium, suppresses myocardial contractility, and lowers mean arterial pressure (MAP) during anesthesia. Dantrolene is an important treatment once rhabdomyolysis is identified in the weeks post-op.

Final Thoughts

The authors could not formulate a specific cause for PAM in warmbloods but encouraged practitioners to warn clients of this potential risk from anesthesia. Attention to details of positioning, padding, and normotension are critical during surgery for all horses, but especially for warmbloods and draft horses. They recommended monitoring muscle enzymes, lactate, and clinical signs in the post-anesthetic period for up to two weeks to facilitate rapid treatment responses for horses developing rhabdomyolysis.

Reference

Hepworth-Warren KL, Goldsmith D, Tsoi M, et al. Post-anesthetic rhabdomyolysis in 7 Warmblood horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc Feb 2025, vol. 263, no.2; DOI:10.2460/javma.24.08.0522

Related Reading

- Sedation and Anesthesia During Equine Emergencies

- Standing Myotomy for Fibrotic Myopathy in Horses

- Causes of Immune-Mediated Myopathies in Horses

Stay in the know! Sign up for EquiManagement’s FREE weekly newsletters to get the latest equine research, disease alerts, and vet practice updates delivered straight to your inbox.