General equine practice has always required round-the-clock emergency coverage that clients can depend on for their horses’ urgent health care needs. An AAEP survey of horse owners and trainers in 2012 revealed that the availability of emergency care 24/7/365 at their horse’s residence was one of the top three criteria for their choice of a veterinarian. Recent studies exploring the reasons behind the low numbers of new graduates entering equine practice and the high numbers leaving the field in their first five years of practice have revealed emergency duty as a strong negative factor in attracting and retaining practitioners. Positions in companion animal practices rarely require emergency duty, as most areas have emergency hospitals dedicated to the urgent and critical care of small pets.

In the United States, more than 50% of equine practices have two full-time equivalent (FTE) veterinarians or fewer. The number of solo practitioners, as measured by AAEP membership demographics, is consistently about 35-40%. The demands of emergency coverage born by a single individual or even by two individuals might understandably lead to exhaustion and burnout.

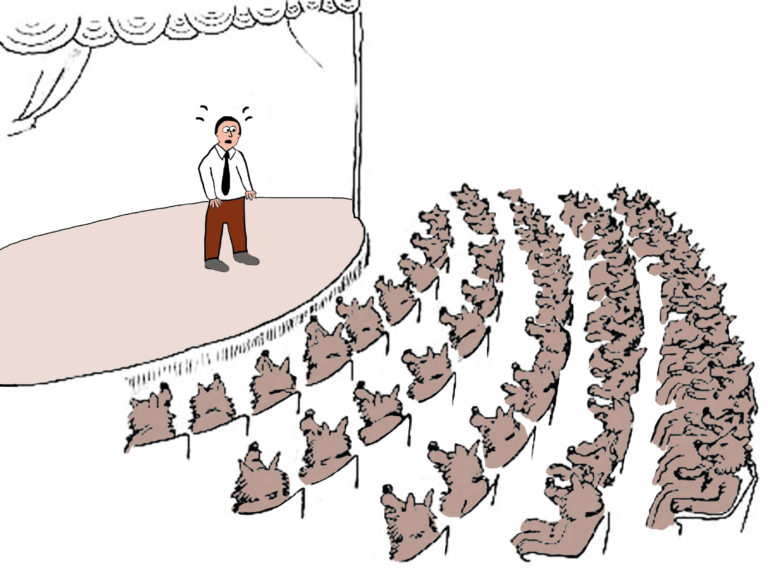

The Emergency Problem

According to Dr. Amanda McCleery in her presentation at the 2021 AAEP Annual Convention, “with the majority of current equine veterinarians being female, the current working conditions required of equine practitioners may simply be untenable for many professionals who are disproportionally burdened by more hours of household work and childcare.”

Even in larger practices where the on-call responsibilities are shared among many practitioners, the larger number of clients means that each emergency shift will likely be very busy. The current paradigm in traditional equine practices is for the doctors who are on emergency call to have a regularly scheduled workday before and after their night on duty. Not surprisingly, this can be exhausting. When a veterinarian is seeing emergencies all through a weekend, he or she might work 12 days straight without a break.

It is no wonder that many are choosing a different path!

Alternatives for Providing Coverage

Alternative models for providing emergency coverage include emergency service cooperatives, referral hospitals with emergency departments, restricting emergency service only to clients, restricting emergency service to those who will haul a horse to the practice facility, emergency-only equine practices and use of relief veterinarians.

The establishment of emergency cooperatives is becoming much more common in areas where there are multiple small practices in which colleagues have cooperative rather than competitive relationships. These emergency co-ops allow a better work-life balance while still providing an important service for clients. This is because co-ops alleviate the demand of providing round-the-clock emergency care, which requires a veterinarian to be available and ready to work at all hours.

For parents of small children, this demand can be difficult if both spouses must work the following day. For single parents, it can be impossible to arrange for emergency childcare in the middle of the night. The uncertainties of emergency demands make planning completely unfeasible.

Why or Why Not?

In 2020, a working group of the AAEP Wellness Committee created an Emergency Coverage Survey, which had a little more than 800 respondents. At that time, 8% of those polled utilized a cooperative model for emergency coverage. There were numerous reasons given for not utilizing such a group to reduce the burden of emergency duty. They included:

- Not enough local practitioners to form a group;

- Treatment of other species would be required;

- Being such a large practice that the burden was already distributed among many doctors;

- Concern over the level of care or diagnostic skill provided by local colleagues;

- Concern they would need to cover too large of a geographic region;

- Concern over loss of clients to other practices;

- Concern over loss of needed revenue;

- Concern about other practices’ fees—too high or too low;

- Fear that their clients would be angry.

In some rural areas that are a veterinary care desert, practitioners struggle to find colleagues with whom to partner in providing emergency care. Collectively sharing the cost of regular relief services is often the only option. Alternatively, if there are referral hospitals within a few hours, this might be a solution.

Sometimes there are only mixed large animal practitioners available for an equine-only vet to partner with. The value of having time away from emergency duty might be worth learning to deal with the most common ruminant and porcine emergencies from your colleague. For some equine vets, however, that is a dealbreaker.

Concerns about other veterinarians in an emergency co-op are often unfounded. You might worry about the skills of other veterinarians, that they will harm your patients with their deficits, or that they might steal your clients with their strengths. Good communication with the cooperative members through monthly dinner meetings, case discussions and hand-offs of cases seen on each shift can often alleviate these fears. Ultimately, having a chance to have time away from your practice has value that usually exceeds these anxieties. After all, if you become burned out and leave practice, your clients will not have you to treat their horses at all.

You might worry about the loss of emergency revenue. But, in most cases, your improved quality of life allows you to be more productive on the days when you are working. If you find that the majority of your income is from emergencies, perhaps rolling out an emergency-only practice would be a good pivot for you.

The fee structures of other practices are not your concern. Each practice has different expenses. Therefore, they might set different fees for the same services you provide. What seems to work best for most cooperatives is to have each doctor be responsible for getting payment from any client/patient they see for an emergency visit. Then, each of the clients’ primary practitioners is updated on cases seen at the end of each on-call period. The update on the case to the regular veterinarian is given by that vet’s preferred method of a phone call, text message or e-mail. The medical records should be emailed.

Be Transparent with Clients

With fewer equine practitioners available, most horse owners are grateful and appreciative to have care. However, some clients are needy and even unreasonable. This should be disclosed to co-op partners.

If you are joining or forming a cooperative, have a seminar to introduce all of the veterinarians to the group of clients being served. This will help the clients feel more comfortable. A golden rule of customer service is not to surprise or confuse your clients. Good communication with clients as you roll out the new emergency co-op is critical.

Many equine practitioners are restricting emergency services to current clients that utilize the practice’s well care services for their horses. This could be defined as having vaccines, a fecal and a dental exam within the last 12-24 months. By confining care for emergencies to horses that have good preventative care, the number of urgent visits can be reduced. However, horses without such care might be left in need. Many practices leave the decision about providing care to non-clients up to the doctor on call. If that practitioner has not been terribly busy, he or she might want to help that animal.

Emergency-Only Practices

An increasing number of practices have fewer doctors on staff after losing associates to positions in companion animal practices. These practices are either no longer offering emergency services or are limiting them to clients who can transport their animals to the practice’s facility. Others provide urgent ambulatory service until late evening, then refer all cases to a regional referral hospital or veterinary school. Some states mandate that each veterinary practice must make a provision for emergency care of their patients, but this can usually be a referral to another practice.

To address the burden of emergency care, the companion animal sector has created a model of emergency care specialty hospitals. Such a model has rarely been adopted by equine practitioners in the United States, but in recent years more emergency-only practices are emerging in areas with robust equine populations.

Some of these practices are supported by subscriptions for emergency coverage from local practices, with those fees covering some of the expenses of the business. Other emergency-only firms rely on busy nights and weekends of emergency care that is priced robustly to support the practice. In that instance, local practices direct clients to call the emergency practice for after-hours care.

Some equine referral hospitals employ emergency-only clinicians and have a separate emergency division. Some relief veterinarians in the equine field regularly provide coverage for small practices to allow those doctors some downtime. A variety of options are developing in response to increased need.

A number of equine practitioners have chosen to specialize in services that only rarely require emergency care, such as integrative care, dentistry or sports medicine. This segregation of services is not unlike the segregation of emergency services in specialized ER practices.

Especially during the pandemic, many practices implemented after-hours telemedicine appointments to triage potential emergency cases. While some patients needed to be seen immediately, others could wait until the next day. By decreasing the number of cases that need an ambulatory visit outside of normal hours, this technological solution can decrease stress and the associated burnout.

Careful consideration of state telemedicine regulations is necessary. Those can be found at the Veterinary Virtual Care Association at https://vvca.org/.

Take-Home Message

Although emergency care for our nation’s horses will always be needed—and greatly appreciated by their owners—new solutions to the burdens of this care are being implemented every year. Creative ways to give equine veterinarians more time for life and better compensation are bubbling up every day in innovative minds.