Credit: Arnd Bronkhorst Photography

Credit: Arnd Bronkhorst PhotographyThe moment you’ve been waiting for has arrived! It’s finally time to begin a search for your long-awaited first full-time time position as a veterinarian. You’ve been working toward this goal for at least eight years and have likely invested more than $250,000 in your education to get to this point.

Ultimately your objective is to find a position that matches the specific type of medicine you’re most interested in practicing, allows you to live within a specific geographic region and pays a lucrative salary.

“The great jobs that many students want to obtain or see other veterinarians performing are the jobs that require experience and years to build that clientele,” said Shem Oliver, DVM, DACVS-LA, associate veterinarian/ staff surgeon at Performance Equine Associates in Thackerville, Oklahoma. “It takes at least five to 10 years to reach that position.”

New graduates face several challenges when searching for and applying to their first full-time positions. “They know a lot about medicine and treating the horse, but have little experience dealing with clientele, managing expectations, communicating and managing the business aspect of the business,” he said.

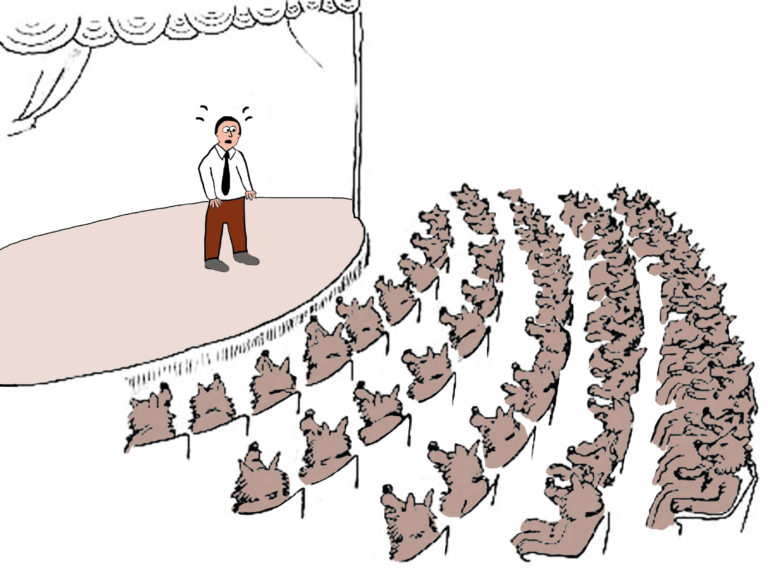

It can be nerve-wracking to have a job and responsibility like you’ve never had before. Even if you are working for someone else, you still have to make all of the decisions yourself and be confident in those decisions. Young, inexperienced veterinarians might also experience difficulty having clients trust them with the animals in which they have invested emotion, money and time.

“Don’t give up,” encouraged Ashley Craig, DVM, an associate field care vet at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute in Lexington, Kentucky. “It’s also important not to waste time (getting started).”

Bridging the Gap

It’s never too early to begin preparing for the transition from veterinary student to working professional. “When I was a first-year student, I was lucky enough to have some senior students tell me to start looking at externships,” said Craig. “That really put the bug in my ear that I needed to plan ahead and to start making arrangements to see as many clinics, and as many cases, as I possibly could in hopes of getting a good externship.” Externships, typically one- or two-week placements with established practices, offer a glimpse into the culture and day-today operations of a veterinary clinic.

“Visiting different practices, I learned a lot about medicine and about different practice formats from these experiences,” said Amanda Spector, DVM, associate at Equine Sports Medicine in Ballston Spa, New York.

These short visits often open doors for longer internships, often viewed as entry-level positions designed to provide valuable experience while perfecting one’s skills under the guidance of an established professional.

“Internships help you gain experience that you’re not necessarily going to see in our veterinary teaching schools,” Craig said. “Internships are a place for you to learn, grow, see multiple styles of practice and to start to gain confidence and develop your own style.”

Today’s veterinary schools provide students a solid foundation in the skills needed in the field, but students might not always have an opportunity to experience and/or treat situations considered routine. “We send our students out to ranches during rotation to practice routine preventative work, but there are some conditions they may never see until working in practice,” said Claudia Sonder, DVM, Director at the Center for Equine Health at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.

Students at teaching hospitals often spend more time interacting with clients whose horses have advanced conditions rather than having an opportunity to intervene at the beginning stages of illness. “Because we are a tertiary care facility, a horse with a foot abscess would not be referred into the hospital. And if a student never happens to see a foot abscess while on rotation, the first time they see it may be in practice,” she explained.

Schools work hard to ensure students experience diverse cases, but sometimes there are skills they don’t gain until working in the field. “My internship was a great introduction to routine and emergency equine practice at a busy referral hospital,” said Spector. “The repetition of emergency and other situations helped me develop clinical judgment from pattern recognition and trust in my skills.”

In addition to honing your skills in a variety of medical situations, internships also offer an opportunity to develop an understanding of the business side of a veterinary practice. “The right internship will allow a young graduate to learn valuable practice experience [and] medicine experience, and make them more marketable to a future employer, without the pressure of ‘producing’ and having a bottom line,” Oliver said.

Established veterinarians can help young veterinarians develop the skills they need for success by serving as mentors. Experienced mentors help new veterinarians transition from student to working professional through guidance and support needed for long-term success. “Good mentorship is very important,” Spector emphasized.

A good mentor offers advice and expertise gained only through years of practice. “It’s so important that new veterinarians have a mentor, someone who is willing to teach them the skills they may not have had an opportunity to practice as frequently in school,” Sonder emphasized.

Location, Location, Location

The job market for veterinarians is strong in many places, allowing a majority of recent graduates to find jobs. “The local economy is a factor in the availability of positions,” Sonder said. “In California, the horse industry is pretty large and vibrant.”

Regions near racetracks and/or venues that are home to performance horse trainers have a higher demand for veterinarians and provide greater opportunities for recent graduates interested in living in a specific area.

At the same time, other economic factors might make an area too expensive to live in. “New veterinarians often have a significant debt burden and face economic decisions based on the cost of living in certain areas,” Sonder added.

Tradeoffs are often part of the decision- making process. “I’m a Kentucky-bred and -raised girl, so I honestly wanted to stay close to home,” Craig said. “But I was open to other locations that had a large Saddlebred population, as that was the horse breed that I grew up riding and showing and was close to my heart.”

Spending time in another region of the country might be necessary to ultimately help you secure a position in the area in which you want to live. Spector’s first choice was to remain in the Northeast and live close to family and friends. However, a one-year internship near San Antonio, Texas, offered the experience needed to find a position in the area in which she wanted to live. “It gave me the experience I needed to feel comfortable in my next position,” she said.

Finding That First Position

Networking plays a significant role in helping connect young veterinarians with good job opportunities. “I was fortunate enough to do several externships at Hagyard’s, then was offered an internship after graduation. Once my internship was completed, I was offered a position,” Craig recalled.

Developing relationships with established professionals is beneficial in often-unexpected ways. “I was not accepted for internship positions at the practices I initially visited; however, veterinarians at those practices connected me with other practices still looking for equine interns, and I had several more interviews via phone, Skype and in person,” Spector said.

Industry-specific job boards such as the one hosted by the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) offer listings for openings around the country. “I found (my current) job through the AAEP website job center page,” Spector added.

Searching the AAEP job center can be helpful early on in your college career. “I first started looking at AAEP’s Avenues page to see what externships and internships were available. I looked at practices that had a heavy emphasis on reproduction and sports medicine and were in a location that I was amenable to,” Craig said.

Throughout the job search process, it’s essential to find a “good match,” which means a practice that fits with the skills and professional development goals you have. “It’s a very synergistic relationship,” Sonder said. “The new graduate brings a wealth of knowledge while learning from a veteran.”

Take-Home Message

Patience is key. “The main thing I try to instill in students or young veterinarians is to be willing to do anything in that job,” said Oliver. “Even if it is something that you do not want to be doing in 10 years, do it, and the stuff that you want to do will come.” That means you might have to do dental floats, vaccinations, sheath cleanings and emergency work, even if that’s not ultimately the work you want to do. “But if you work hard and do a good job, those lameness appointments will come,” Oliver said.