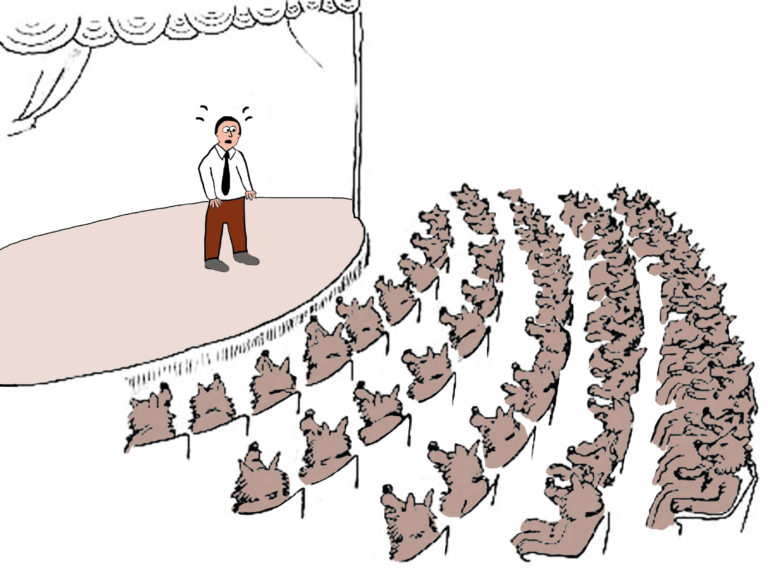

Clients today expect a model of care that is relationship-centered rather than dogmatic. Credit: Arnd Bronkhorst Photography

Clients today expect a model of care that is relationship-centered rather than dogmatic. Credit: Arnd Bronkhorst PhotographyIn your clinical vision of how to approach a horse’s problem, you probably have specific steps mapped out in your mind in order to arrive at a good outcome. Yet, in veterinary medicine, one of the pressing challenges is how to inspire your clients to accept and follow through on your recommendations. In human and animal health industries, this has been an area of concern, with much study directed at solving the dilemma of client compliance.

With the new vaccination requirements from USEF, you have an opportunity to reinstate yourself in the basic health care of your clients’ horses, since you will probably be their go-to source for information about compliance with this rule. You can use this discussion to help clients become more amenable not only to competition vaccination requirements, but other aspects of well-horse care.

Without question, good communication is a key element in eliciting the best compliance behavior from your clients. To help you better understand how to gain this client compliance, we turned to Colleen Best, DVM, PhD, of the Ontario Veterinary College, who earned her PhD with a thesis on interpersonal relationships in equine practice. She offered many insights on how good communications can be achieved to elicit optimal cooperation from horse owners.

While the term “compliance” is often used, she advises that the phrase “adherence to recommendations” would be more correct (and less authoritative).

Types of Adherence Issues

We ask our clients to follow our lead on suggestions about which immunizations to give and when to give them, as well as which medications to give and how often. We ask them to pursue our recommendations on diagnostic pursuits (state-of-the-art imaging, endoscopy, etc.) and therapeutic options (surgery, joint injections, regenerative therapy, etc.), many of which can be quite costly. We propose therapeutic plans for rehabilitation following surgery or injury and expect clients to follow the directions exactly.

But experience has shown that a vet’s recommendations are not always followed. Sometimes, the recommendations are ignored altogether; sometimes they are modified so significantly that they can’t get the horse to the desired result, even though they are doing “something.”

Historically, veterinarians have suspected that lack of adherence to recommendations is due to financial, time or convenience factors. Certainly, adherence can be complicated by a client’s lack of funds to allow us to provide the offered care. Additionally, treatment regimens might be curtailed due to client time constraints (work, family obligations, etc.) and/or for logistical reasons (i.e., the client can’t get to the barn to do the treatment). However, clients often report that they fail to follow recommendations because of poor communication from their veterinarians. Possibly a veterinarian has not made a strong enough case about the reasons for the recommendations, or, in other cases, the instructions weren’t clear or understandable to the client.

Perhaps a client doesn’t fully believe that what his or her veterinarian is recommending is appropriate or is the correct approach. In that case, the client will be resistant to anything you plan, but might not express the reason to you.

Best noted that another reason for lack of adherence is that it is difficult for clients to hear everything that their veterinarians are saying, and they might not fully grasp what is happening with the horse or understand the situation. Or they might have different notions based on what other people have said—for example, a trainer, farrier, alternative therapist or “Dr. Google.”

So how do you approach these situations? Is it your job to persuade or sell a client on a course of action?

“The veterinarian is not a salesman, but rather our role is to educate,” stressed Best. “It is important to explain and educate about what we believe and why specific measures are appropriate. Then we can work with the client to find an affordable and practical solution.”

Such problem solving is a test of a veterinarian’s creativity. Clear communications and relationship-building are keys to this resolve.

Barriers to Adherence

Adherence has been defined by the World Health Organization’s Adherence Project as the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with agreed-upon recommendations from a health provider. This focuses the issue on the relationship between client and practitioner, with both parties in the partnership to follow through on a mutually agreeable plan. The American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) collaborated with Pfizer Animal Health in 2008 to investigate factors that contributed to poor adherence to recommendations. Looking at identifiable barriers to medication adherence in human medicine, the study assumed that similar barriers existed for veterinary care. In human medicine, nearly half of all patients were found not to follow their doctors’ recommendations. The AAHA study identified about the same level of non-adherence for pet owners. Some barriers included:

- psychological factors (concerns about adverse side effects, denial about need, forgetfulness or lack of obvious or acute symptoms, so treatment is stopped);

- lack of a clear recommendation by the veterinarian;

- lack of understanding or belief in the importance of the medication;

- length of therapy, complication of regimen and cost;

- ineffective or incomplete communication between patient and physician.

For clients to be adherent to recommendations requires that they believe in what their veterinarians are telling them, and that they have confidence in their own abilities to carry out the recommendations. Sometimes it is helpful to put yourself in your client’s “shoes” and see how well your recommendations could work for you. In a 2012 New York Times article, Dr. Danielle Ofri did an experiment with her medical students: She asked them to use Tic-Tac breath mints as their “medicine” and follow a fictitious prescription for a week.

She said, “When we met for our next session, I asked them how they did, and they all had abashed expressions on their faces. Not one was able to take every single ‘pill’ as directed for seven days.” While you might feel your recommendations are reasonable, it is entirely possible that there are logistical reasons for your clients’ inability to fulfill the requested plans. Another study that reviewed patient-physician interaction identified four areas that greatly influence adherence: healthcare education, negotiating a plan, an active role for the patient/client, and expressions of empathy and encouragement by the doctor. Other factors that have been shown to have great influence on client adherence include:

- the amount of time the veterinarian spends at the visit;

- the provision of verbal and written instructions;

- the assurance that instructions are understood; and

- follow-up communications.

What Does It Mean to Be a Good Communicator?

Communication takes two forms: listening and speaking. Listening enables you to know what the client is able to manage in care for his or her horse.

“Being a good listener is achieved by choosing to listen and actually listening,” said Best. “Most of the time we are thinking about what to say or do next, and/or we listen judgmentally. Expressing curiosity by actually wanting to hear what the client has to say often yields more information.”

As Best suggested, “It is best to keep your mouth closed until the client has had their say. Don’t interrupt unless it is relevant to the conversation. Then present a summary or paraphrase of what they have said, so they know you have heard and understood.”

Often you can carry on a conversation that allows a client to present information while you are performing a task such as wound cleansing, joint scrubbing or performing a rectal palpation.

Communicating by speaking relies on imparting information in a neutral way, and by using language a client can easily understand at a pace that he or she can absorb. Lacing your conversation with unexplained medical and technical terms will only cause a client to tune you out and feel intimidated. It is important to simplify your language, since it is unlikely that your client will interrupt to advise you that he or she doesn’t understand the technical terms.

A trusting relationship is important for adherence to recommendations about what is in the best interest of the horse, which is not always what is best for the client. Although you are presenting options, this doesn’t exclude your option of making specific recommendations.

“There is usually more than one way to get something accomplished,” stated Best. “Presenting an attitude of wanting to partner with a client and be on the same team often elicits the most trust and cooperation.”

Such a relationship-centered approach to a partnership in managing the horse’s health care is the ideal way for achieving adherence and the best outcome for the horse. A study (JAVMA 2006) comparing different communication patterns between veterinarian and client reported, “A relationship-centered approach includes exploration and discussion of biomedical and lifestyle-social topics, as well as building rapport, establishing a partnership and encouraging client participation in the animal’s care, which has the potential to enhance outcomes of veterinary care.”

Imparting information in a neutral way is important so a client can feel that he or she is arriving at a decision without being pushed into a specific path. Some examples of how this is accomplished:

- Understand the client’s expectations. For example, although stem cell treatment might be a viable option, if the horse is a pasture pet, then that probably isn’t the most practical advice.

- Assure the client that his or her decision needs to be right for that client and that client’s horse.

- Provide your recommendations while also presenting other options that might yield similar results.

This approach doesn’t change the information you present, but rather how you present it. As Best explained, “Part of the veterinary standard of care is to present all options and let the client choose.”

Part of describing options is informing the client about the risks and benefits of each option while personalizing the discussion for his or her particular animal. Allow the client to weigh in with questions and comments.

“In the end, what they can or will do is not our decision to make,” stressed Best. “It is critical that the veterinarian doesn’t imply a judgment of the client’s decision, but rather honors their decision, no matter what it may be.”

While the veterinarian is an advocate for a prescribed course of action, expressing empathy and validating a client’s feelings go a long way toward achieving adherence to recommendations.

Gathering information can rely on asking open-ended questions; these questions begin with “how,” “what,” “why” and “please describe,” as some examples. In open-ended questions, the person is encouraged to reflect, then to express, whatever is on his or her mind. By contrast, closed questions generally have a “yes” or “no” answer.

While comments from clients asked open-ended questions are often informative, this type of question can also result in digressions that are time-consuming but not instructive. So how to keep the client on track? Best suggested, “Go back to the original expectations of outcome, then focus in on this with an open question. For example, ‘This is why I am asking,’ or ‘This is the type of information I’m looking for.’ ”

She said that short interruptions are okay to get a client back in focus, especially if done politely. You might say, “Sorry to interrupt, but I want to make sure I have this right and have heard you correctly.”

Best noted, “Many times people keep talking because they aren’t sure the other person has heard or understood them, or because they are simply nervous.”

In general, it has been noted that the greatest rapport between practitioner and client occurs when the conversation is laced with positives like laughter, compliments, agreements and approval. Through improved relationships, adherence is likely to improve.

Another key element in effective communications is ensuring that your client has no other questions before you leave his or her presence. It is important to also provide that person with a safety net: “If something happens or you have further questions, please don’t hesitate to call.”

“This prevents the client from feeling abandoned or overwhelmed by the caretaking of the horse’s problem,” said Best.

It can only improve the bottom line for adherence if you take the trouble to call or email your client following your visit to ask how he or she is doing with the therapeutic plan, and whether there is anything you can do to help his or her efforts.

Alternative Communication Methods

Face-to-face interactions provide not just verbal information between people, but also non-verbal cues that include body posture, eye contact, facial expressions, nodding, facing the client who is speaking, sitting or standing on the same level and not interrupting.

These are just a few examples of nonverbal indicators of your interest in the client’s words. Added to this are more obvious verbal cues, such as pauses between comments and questions, paraphrasing a client’s voiced concerns and comments, display of empathy and tone of voice.

“On the other hand, phone interaction is para-verbal,” said Best. “It includes your tone, speed of speech and the specific language you use. However, it can be quite problematic and frustrating in today’s world, where we often speak cell phoneto- cell phone with intermittent or poor reception. This makes it more dangerous that something you say may be misunderstood or misinterpreted.”

Best said that you should be aware of how you sound over the phone. A recent experience that affects your emotions can be apparent in your voice. For instance, if you just had to euthanize a horse at the previous vet call, you might still be upset, and that emotion can travel through the phone.

“We send more signals than just words over the phone,” she said.

As for email interactions, it is not uncommon for the tone to be misconstrued. Best said that email or texting cannot replace an actual phone conversation or recheck appointment.

By suggesting that you re-examine the horse, you give the impression that you are accessible and invested in the horse’s care. Although it might be tempting to try to manage a case over the phone, this could be a disservice to the horse. In cases where it might be necessary to modify the original plan, that is best done by being on site with the horse and in a face-to-face conversation with the client.

The best way to achieve adherence to recommendations is to maintain close follow-up; then, if some technique isn’t working, you can quickly turn to another option of treatment.

How to Maximize Client Understanding

“Companion animal research has identified that explanations should be presented in a way that matters to the client,” remarked Best. “This means the vet must understand what the client wants to do with the horse, as well as the client needing to understand the purpose of the recommended therapy. This level of communication and education gives you an opportunity to train the client to take better care of the horse. Their enhanced understanding also makes your job easier.”

In general, studies have found that verbal information retention is poor; what we hear and what we pay attention to is relatively small compared to what was said. Best suggested that it is helpful to include on the invoice a brief description of what was done. “This serves as a written reminder of what transpired during the clinical visit, and it improves a client’s understanding and appreciation for the value of your exam and treatment,” she emphasized.

Handouts are great, as well, although many clients are likely to access the Internet. What could work best is to point them in a direction via specific websites or links that provide the most correct information, rather than letting them take their chances with “Dr. Google.”

Financial constraints certainly influence how well a client will carry through with your recommendations. Best said, “It helps to ask ‘What resources are you willing to dedicate to this problem? We have some options that vary in terms of time and cost.’ ”

If the vet understands the client’s constraints, then that helps with formulating a useful plan that has the strongest possibility of adherence to recommendations. She added, “Knowledge is power, and therefore to do what is best for the horse means you need to understand what works for each client and his or her unique situation.”

Another key point identified in companion animal studies is that clients really want to be understood, and they want their vets to understand their capacity to provide care.

“It is dangerous to make assumptions about what a client will or won’t do,” advised Best. We might think we know our clients’ resources just by visiting their farms or seeing the rigs they pull in to our clinic, but who’s to say they won’t be motivated to take out a loan or ask a friend or family member for financial assistance?

“Clients want to be the ones to make their decisions based on knowing what all the options are, even if some are not logistically (or financially) possible,” she advised.

Expectations are another key element of where adherence to recommendations might fall apart. “The expectations a client brings to an interaction with his or her veterinarian become the yardsticks of success or failure,” observed Best.

This is where education through communication is all-important. “What you as the practitioner may take for granted when things go as you expected may actually be making the client unhappy. Some clients will give up halfway through a therapy unless you set up an appropriate expectation of progress, as well as ongoing costs.”

An unhappy client is not only less likely to follow through on your recommendations, but is more likely to leave your practice and start using another veterinarian.

Minimizing Interference From Outside Influences

Another challenge to equine practitioners is the degree of outside influences that “inform” a client’s decision-making process. Often, the veterinarian is not the only caretaker of the horse’s needs; clients reach out to trainers, barn managers, farriers, acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, rolfers, equine dentists and various other support persons.

Many times, the client is then invested with erroneous or misleading information from people who might have the best of intentions, but are not qualified to diagnose a problem or offer appropriate therapeutic solutions. Friends also chime in with ideas based on their personal experiences or their veterinarians’ recommendations, which might have little or nothing to do with the case at hand. When the ideas and suggestions are in conflict with what you are proposing, it is difficult to achieve adequate adherence to your recommendations.

“It is helpful to ask clients what they know and what their experiences may have been before you start explaining the issue at hand,” said Best. “This gets at what they remember, gives you an idea of their starting point, and informs you as to how much educating you have to do. It also identifies what pieces of conflicting information and misinformation your client is holding onto. Often the misinformation may be based on historic ways of doing things that are no longer appropriate. Such a conversation gives you an opportunity to clarify and correct for the current situation.”

While trainers, farriers and other support people create interference with their ideas and suggestions, one approach to mitigating such influences is to invite these people into the conversation. “The hardest thing to manage is the voice you’ve never heard,” said Best. “It is important to get away from the triangulation that puts the client smack in the middle of differing opinions that force them to choose. It is best to ask the client if you can speak directly to the farrier, trainer or barn manager, for example. If you don’t offer this, it is possible that your client will end up switching veterinarians due to conflicting ideas.”

Best added that such conversations with ancillary support persons can be productive to your practice in other ways: You might end up forming a relationship with a new potential client who respects your candid approach and communication skills.

Interruptions in Communications

All things that interfere with communication are likely to interfere with a client’s focus, and therefore with adherence to recommendations. This includes your phone and/or pager, as well as many clients’ propensity to access their smartphones every few minutes or chat with others in the barn. Best urged, “Your job is to manage the situation. It may even be necessary to rebook an appointment if you or they can’t be mentally focused. If your pager keeps going off with an emergency, you are distracted. If a client is perpetually distracted by ‘this and that’ at the barn or their cell phone, then you won’t be getting your information through to them. Both parties need to be ‘present’ in the full sense of the word. This takes a lot of self-awareness of the situation and the courage to speak up about it.”

Best suggested offering a simple comment like, “Please let me know when you are ready to discuss …” This has the potential to get client focus back on track.

Another issue is safety, and Best said there can be no compromise regarding safety. If a client is holding the horse while you are injecting hocks, then he or she needs to put the cell phone away and not converse with others in the barn, instead focusing on handling the horse. It is relevant to point out to these clients that your life is in their hands, quite literally.

Similarly, a veterinarian who gives an impression that he or she is in a hurry does little to engender trust, and this detracts from any heartfelt empathy the vet might feel for the horse, the client and the situation. In social psychology, the concept of reciprocity theory implies that individuals respond to positive actions with positive actions and respond to negative actions with negative ones.

In this case, if you are rushed and communications are compromised, then your client’s adherence will suffer. Your best strategy is to schedule appointments with ample wiggle room so you don’t get stacked up too tightly during the day. If staff members schedule your day, educate them about the importance of providing a client with sufficient time and attention, so you aren’t rushed from one appointment to the next.

The Role of Office Staff and Technicians

Office staff and technicians have additional important roles in reinforcing your message. Companion animal studies have found that actions of practice team members significantly affect pet owner behavior. Best pointed out that staff members and technicians are often helpful with creative problem solving.

Best noted that staff members and technicians are quite adept at providing a communication bridge between the horse owner and the veterinarian. This can be accomplished by having them say something like, “Here is my experience,” explaining that on a personal level. Personalizing the course of action is much more understandable than the client trying to mull over the value behind a statistical summary of results of a therapeutic plan. When such communications reinforce your message, better adherence to recommendations is achieved.

“What is most important,“ said Best, “is that your staff members are consistent regarding the messages that come from your office. You, as the professional, may have to educate your staff as to what message you want them to impart.”

Alternatively, a staff member should not hesitate to simply say, “I will relay your question and have Dr. Veterinarian call you back.” It helps to empower the staff to ensure that everyone is on the same page.

The same need for consistency in philosophy and messaging holds true between veterinarians in multi-doctor practices. You might discuss some of these ideas in clinic rounds so there is a clear message among all doctors to all the practice clients. Otherwise, clients tend to use this as a wedge between practitioners, and if there isn’t harmonious agreement, a client is less likely to adhere to recommendations.

Furthering Your Skills

To acquire more communication skills, Best advised attending seminars. The AAEP and many mixed-animal conferences offer practice management continuing education, including an emphasis on communication. More of these educational opportunities are becoming available, so Best advised that vets be on the lookout for them.

Take-Home Message

In today’s medical world, both human and veterinary, clients are expecting a new model of care that is relationship-centered rather than dogmatic. No longer does the bossy approach of “I’m the all-knowing doctor” work to achieve best outcomes. Instead, clients want to feel that they and the veterinarians are partners and will work together on behalf of the horses.

As Best pointed out, “Any gender or age of veterinarian can be relationship-focused in their approach.” Clients appreciate thoroughness, good communication skills and vets who take the time to address their issues. “When you have developed a good relationship with your client, are creative with your therapeutic plan, and understand what the client needs, then adherence to recommendations improves,” she said.