Equine practitioners don’t often encounter zoonotic diseases. Yet one that is particularly noteworthy is the fatal disease rabies. There is significant importance in protecting horses and humans from rabies exposure, and veterinarians play an important role in this.

To address vet liability and health risks associated with rabies, a panel of experts spoke at a Zoetis-sponsored Sunrise Session at the 2017 American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) Convention. Bonnie Rush, DVM, MS, DACVIM; Susan Moore, MS, PhD; and Denise Farris, JD, shared their expertise with attendees.

Initial signs of illness don’t always definitively form a diagnosis of rabies in a horse, since signs vary at different times in the course of the disease. Usually a bite is not evident at the time clinical signs appear because incubation can take up to four months, depending on location of the bite. For example, virus injected into a distal limb might take one to three months to enter the central nervous system.

Signs of Rabies

Rush described a variety of confounding and usually asymmetrical signs seen in horses with rabies:

- abnormal behavior

- reduced appetite

- difficulty swallowing and/or pharyngeal paralysis

- ataxia

- altered vocalization

- fever

- hind-limb lameness that progresses to paresis

- intention tremors

- hyperesthesia

- recumbency

- paralysis

- seizures, usually seen at the end stage of infection

Many of the clinical signs can be confused with other neurologic syndromes, such as West Nile virus or head trauma.

When a veterinarian is called out to examine a horse with neurologic disease that turns out to be rabies, many people become involved: veterinarians, physicians, laboratory personnel and personnel in the local public health system. Handling of tissue must follow strict precautions, such as using personal protective equipment including gloves, gowns, and face and eye protection.

Rabies virus is passed through bites and through wounds or mucous membranes that come into contact with infectious saliva or nervous system tissue.

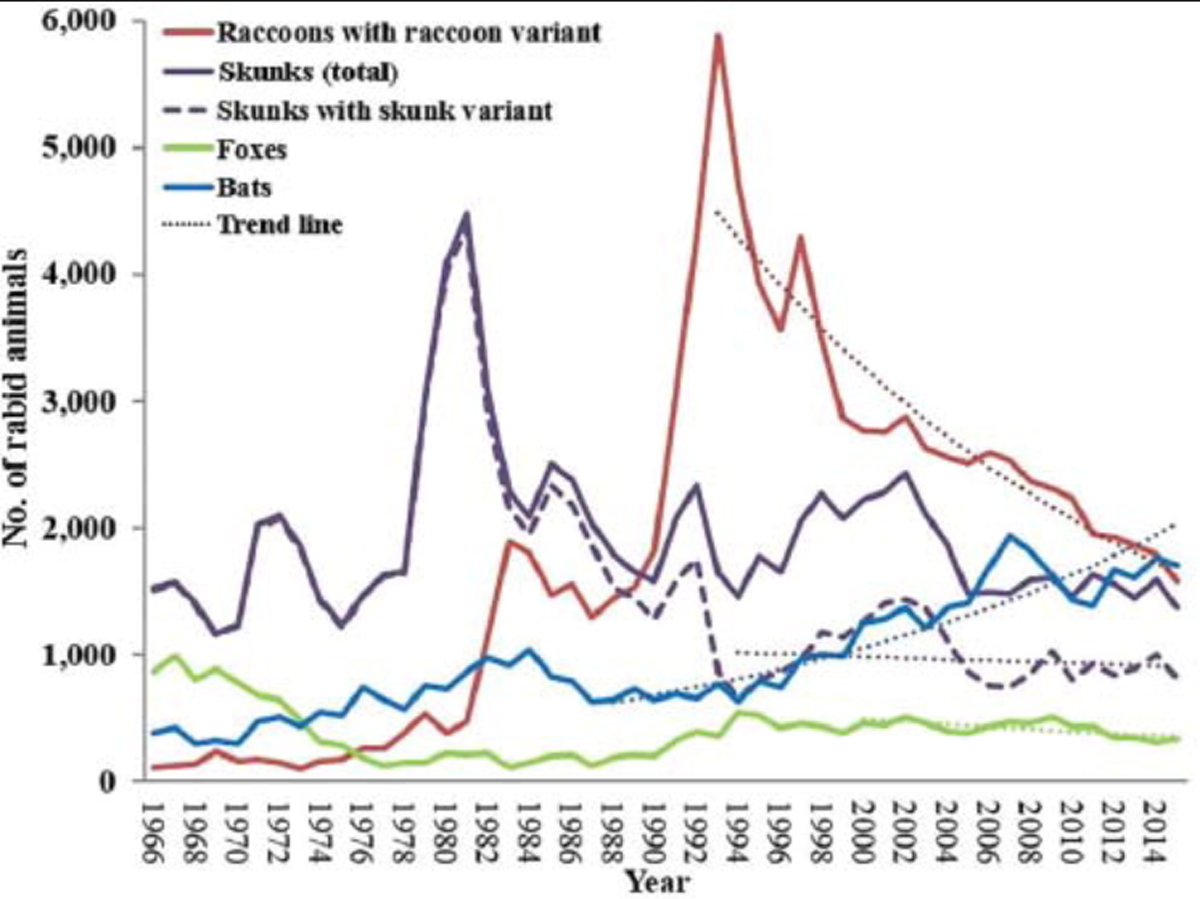

Cases of rabies among wildlife in the United States, by year and species, for 1966 through 2015.

Cases of rabies among wildlife in the United States, by year and species, for 1966 through 2015.Diagnostic Protocols

For an accurate diagnosis, it is helpful to send the whole brain with brainstem, cerebellum and some spinal column attached. Rongeurs should be used to obtain the head and associated spinal cord. It is important not to use a band saw as that aerosolizes tissue and virus, posing a hazard to humans involved in sample acquisition.

Similarly, it is not suitable to test cerebral spinal fluid due to increased risks to human health. Sending in only half a section of the brainstem cannot yield a definitive diagnosis. Moore pointed out that brain tissue can test negative for rabies, yet the spinal cord of that same horse can test positive. Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing done on these neurologic tissues is the test of choice.

All lab samples must be marked as suspect for rabies, and the lab should be notified in advance of receipt.

In a horse is suspected of having rabies, it is important to ask the owner about the extent of exposure to facilitate rapid identification of all humans and animals that had contact with the horse. This enables prompt post-exposure prophylaxis in humans and quarantine of animals. Anyone in contact with the horse either before or after its death should receive prophylactic vaccines.

Once a horse is examined and there is a suspicion of rabies, but the horse is not immediately euthanized, quarantine procedures are put in place. Anyone going in and out of the stall must wear complete personal protective equipment, with no exceptions. A log on the outside of the stall should be used to record every entry and time of entry.

Veterinarians are tasked with following biosecurity protocols when it comes to protecting employees from the risk of potential exposure to rabies. Personal protective gear must be used, and it is prudent to have employees immunized with rabies vaccine if they are working around horses. Post-exposure vaccine costs can run $2,000- $7,500.

Horses share an environment with animals that can carry rabies.

Horses share an environment with animals that can carry rabies.Liability Associated With Rabies Management

The AAEP, the AVMA and the National Association of Public Health Veterinarians (NASPHV) all have stipulated that equine rabies vaccination is a core vaccine—i.e., it is “a standard of practice commonly accepted within the industry.” Should a veterinarian be faced with legal action for negligence in regard to mismanaging rabies vaccine recommendations and protocols, this criterion is the legal standard used in court and in front of a jury.

Horses are uniquely at risk because they are housed outside, close to rabies-carrying wildlife reservoirs. It is possible for exposure to occur even if horses are stabled. Farris said there are different protocols in different states, so it is important to know your state regulations for compliance and maintenance of the defined legal standard of care. Rabies-endemic areas are abundant throughout the continental United States, but especially notable in Texas, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Kansas.

Thirty-two states require that veterinarians buy and administer rabies vaccine; in other states, owners are able to obtain vaccine and immunize their own horses. For information about state regulations and statutes, as well as who is legally allowed to immunize for rabies, refer to www.rabiesaware.org.

Once a veterinarian establishes a veterinarian-client-patient-relationship, he or she now has the responsibility to advise clients about core vaccines, of which rabies is a primary one considered in the established standard of care.

If a client refuses to immunize against rabies, then the veterinarian should get a waiver in writing from the horse owner. The owner must also sign a statement verifying that he or she has read disclosures and warnings about rabies, and that he or she assumes all associated risks should the horse contract rabies.

AVMA protocols for an owner’s refusal to vaccinate against rabies are specific. A waiver may be issued if there is clinical evidence that the horse is at “considerable risk” of harm from the vaccine due to other medical conditions. Geriatric age and/or an owner’s antipathy to vaccines are not justifiable reasons for declining rabies immunization recommendations by a veterinarian. It is important to point out to horse owners that currently available killed virus or recombinant rabies vaccines are not able to induce rabies in a horse; these vaccines are safely used, even in immune-compromised horses. Modern rabies vaccines are almost 100% effective and should be given annually.

For any horse that is unvaccinated, the following measures should be taken.

Euthanasia is recommended if an unvaccinated horse has been exposed to rabies. If the client refuses to euthanize, then the horse is confined under strict biosecurity protocols and observed for six months.

For a vaccinated horse exposed to rabies, another rabies booster is given immediately and the horse is observed for 45 days for rabies clinical signs.

For a rabies-exposed horse with an outdated vaccine history, state statutes stipulate the appropriate course of action, and local public health authorities provide guidance on a case-to-case basis.

To date, there have been no reported cases where an equine veterinarian has been held liable, but there are cases of small animal negligence.

If you, as a veterinarian, suspect rabies, then it is your responsibility to take specific steps to protect humans in contact with the horse, as well as yourself:

- Advise the owner about potential exposure and recommend that he or she consult with a personal physician and seek treatment.

- Document the conversations in the medical record. There must be specifics in the documented record; it is not sufficient to make general record-keeping entries. This recommendation is based on small animal veterinarian experiences.

- Obtain the horse’s vaccine history. Discuss euthanasia or the six-month quarantine required for unvaccinated, but exposed, horses.

- Your professional liability insurance will cover ordinary negligence occurrences. However, Farris stressed that the more a horse presents with rabies signs, and the less a veterinarian does, the more this crosses over into gross negligence, which is not well covered by liability insurance policies.

To sum up, Farris used the example of the “front-page-of-the-newspaper rule.” How would you feel if your situation was published on the front page because you didn’t follow protocol? This should motivate practitioners to take all precautions and to follow all recommendations regarding horse exposure to rabies.